Franz von Papen: (Ribbentrop was) a man of markedly elegant appearance, always impeccably dressed, who spoke perfect English and French. Unfortunately, these qualities did not suffice to make him a statesman. Normally, a man of his education and background could have been expected to be a success in high office. In Ribbentrop's case there were insurmountable obstacles. He was immensely industrious, but devoid of intelligence; having an incurable inferiority complex, his social qualities never matured as they should have done.

French ambassador to Berlin Robert Coulondre: Hitler launches into monologues when carried away by passion, but Herr von Ribbentrop does so when he is ice-cold. It is futile to challenge his statements; he hears you just as little as his cold, empty, moon-like eyes see you. Always speaking down to his interlocutor, always striking a pose, he delivers his well-prepared speech in a cutting voice; the rest no longer interests him; there is nothing for you to do but withdraw. There is nothing human about this German, who incidentally is good-looking, except the baser instincts.

Mussolini: Ribbentrop belongs to the category of Germans who are a disaster for their country. He talks about making war right and left, without naming an enemy or defining an objective.

April 30, 1893: Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim Ribbentrop (later Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop) is born in Wesel (now in North Rhine-Westphalia); the son of a German Army officer. As a young man, he will live at various times in Grenoble, France, and London.From Ribbentrop's IMT Testimony: I came from an old family of soldiers. My mother came from the country. I went to school at Kassel and Metz in Alsace-Lorraine. There, in Alsace-Lorraine, I had my first contact with the domain of French culture; and at that time we learned to love that country dearly. In 1908 my father resigned from active military service. The reason was that there were differences at that time connected with the person of the Kaiser. My father already had a strong interest in foreign politics and also social interests, and I had a great veneration for him. At that time we moved to Switzerland and after living there for about one year I went to London as a young man, and there, for about one year, I studied, mainly languages. It was then that I had my first impression of London and of the greatness of the British Empire.

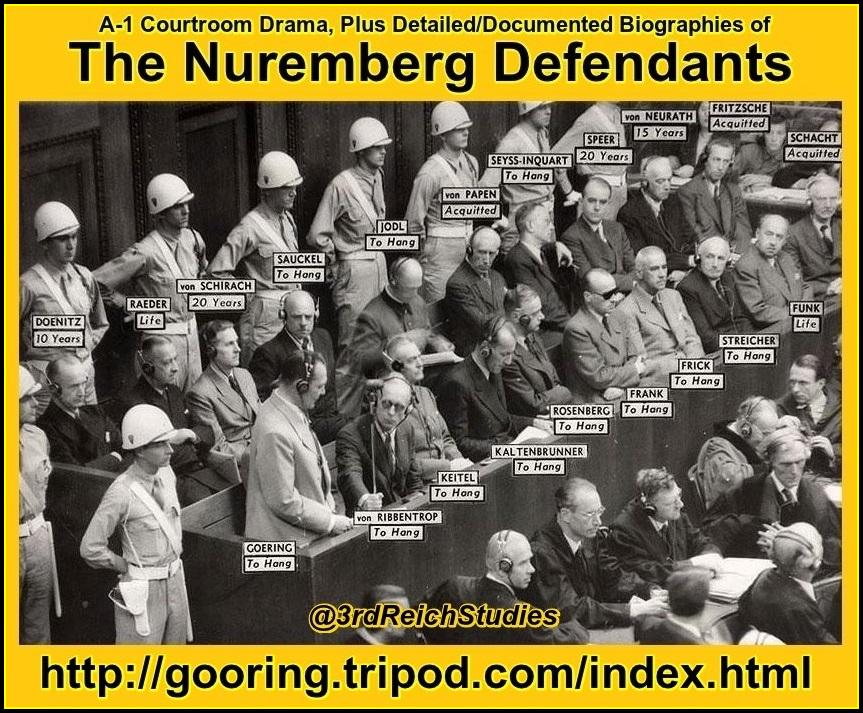

Note: The source for most items is the evidence presented to the International Military Tribunal (IMT) at the first Nuremberg Trial, between November 21, 1945 and October 1, 1946. As always, these excerpts from trial testimony should not necessarily be mistaken for fact. It should be kept in mind that they are the sometimes-desperate statements of hard-pressed defendants seeking to avoid culpability and shift responsibility from charges that, should they be found guilty, could possibly be punishable by death. (To reduce redundancy, many of the ‘vons’ have been ignored by design, with the ‘von Ribbentrop’s’ becoming simply ‘Ribbentrop's.)

1910: Young Ribbentrop crosses the Atlantic, eventually settling in Ottawa, Canada where he works as a timekeeper on the reconstruction of the Quebec Bridge and the Canadian Pacific Railroad. This is followed by employment as a journalist in New York City and Boston. He will eventually become the owner of a small business, importing German wine and champagne.From Ribbentrop's IMT Testimony: After about one year, in 1910, I went to Canada. Originally I wanted to go to the German colonies, but then I went to America instead. I wanted to see the world. I remained in Canada for several years, approximately two years as a worker, a plate layer on the railroad, and later on I turned to the bank and building trade.

August 15, 1914: Following the outbreak of World War One, the patriotic Ribbentrop leaves his business in Canada and obtains passage on the Holland-America ship The Potsdam, leaving Hoboken, New Jersey for Rotterdam. As soon as he finally reaches Germany, he enlists in the 125th Regiment of the Hussars. Ribbentrop will reach the rank of first lieutenant, and be awarded the Iron Cross.From Ribbentrop's IMT Testimony: In 1914 the first World War caught me in Canada. Like all Germans at the time we had only one thought—"Every man is needed at home and how can we help the homeland?" Then I traveled, to New York, and finally in September 1914, after some difficulties, I arrived in Germany. After serving at the front, for approximately 4 years, and after I had been wounded, I was sent to Constantinople, to Turkey, where I witnessed the collapse of Germany in the first World War. Then I had my first impression of the dreadful consequences of a lost war. The Ambassador at that time, Count Bernstorff, and the later Ambassador, Dr. Dieckhoff, were the representatives of the Reich in Turkey. They were summoned to Berlin in order to take advantage of Count Bernstorff's connections with President Wilson and to see--it was the hope of all of us--that on the strength of these Points perhaps a peace could be achieved and with it reconciliation’s.

1916: After being seriously wounded, Ribbentrop is stationed in Istanbul as a staff officer. During his time in Turkey, Ribbentrop will befriend another officer, Franz von Papen.October 21, 1918: From a proclamation of the German-Austrian deputies after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy:

November 12, 1918: From a resolution passed one day after the Armistice by the Provisional Austrian National Assembly:

March 1919: Ribbentrop joins the War Ministry and will eventually be a member of the German delegation that attends the Paris Peace Conference.

From Ribbentrop's IMT Testimony: After some difficulties, in March 1919, I came to Berlin and I became adjutant of the then General Von Seeckt for the peace delegation at Versailles. Subsequently, when the Treaty of Versailles came, I read that document in one night and it was my impression that no government in the world could possibly sign such a document. That was my first impression of foreign policy at home. In 1919 I resigned from the Armed Forces as a first lieutenant, and I turned to the profession of a businessman. Through these business contacts, I came to know particularly England and France rather intimately during the following years. Several contacts with politicians were already established at that time. I tried to help my own country by voicing my views against Versailles. At first it was very difficult but already in the years 1919, 1920, and 1921, I found a certain amount of understanding in those countries, in my own modest way. Then, it was approximately since the years 1929 or 1930, I saw that Germany after seeming prosperity during the years 1926, 1927, and 1928 was exposed to a sudden economic upheaval and that matters went downhill very fast.

September 6, 1919: From a speech by Prelate Hauser, President of the Austrian Parliament, discussing reasons to accept the harsh conditions of the Peace Treaty of St. Germain:September 10, 1919 Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye: The new Republic of Austria signs the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye under tremendous pressure from the victorious Allies. The Austrian equivalent of the Treaty of Versailles, among its provisions are; the new republic's initial self-chosen name of German Austria (Deutschoesterreich) has to be changed to Austria; the new Republic of Austria, consisting of most of the German-speaking Alpine part of the former Austrian Empire, must recognize the independence of the newly-formed states of Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs; must submit to "war reparations"; must refrain from directly or indirectly compromising its independence, which means that Austria can not enter into political or economic union with Germany without the agreement of the council of the League of Nations; the Austrian Army is limited to a force of 30,000 volunteers. Note: The forcible incorporation of the German-speaking population of the border territories of the Sudetenland into the artificially-created state of Czechoslovakia will lead to the Munich Conference and become one of the causal factors of WW2.

January 10, 1920: Entry into force of the Versailles Peace Treaty and of the Covenant of the League of Nations.

From Ribbentrop's IMT Testimony: I have already

mentioned the disappointment I experienced as a young officer through

personal contacts, in particular, with the German Ambassador at that time,

Dieckhoff, who is a distant relative of mine or relative by marriage, the

disappointment which in fact we all experienced in the German Armed Forces,

among the German people, and in government circles naturally even more--that

these Points of Wilson had been so quickly abandoned. I do not propose to

make a propaganda speech here. I merely want to represent the facts soberly

as I experienced them at the time. There is no doubt that the

defenselessness of the German people at that time led to the fact that

unfortunately a tendency was maintained among our enemies not toward

conciliation but toward hatred or revenge. I am convinced that this was

certainly not the intention of Wilson, at that time President of the United

States, and I myself believe that in later years, he suffered because of it.

At any rate that was my first contact with German politics. This Versailles

now became. ....

But it is known that even the severe stipulations

of Versailles as we experienced them, from the closest personal observation,

were not adhered to as is well known. That, too, is perhaps a consequence,

an after-effect of a war, in which men drifted in a certain direction and

just could not or would not adhere to certain things. It is known that the

stipulations of Versailles were not observed then either territorially

speaking or in other very important points. May I mention that one of the

most important questions--territorial questions--at that time was Upper

Silesia and particularly Memel, that small territory. The events which took

place made a deep impression on me personally. Upper Silesia particularly,

because I had many personal ties there,and because none of us could

understand that even those severe stipulations of Versailles were not

observed. It is a question of minorities which also played a very important

part. Later I shall have to refer to this point more in detail, particularly

in connection with the Polish crisis. But light from the beginning, German

minorities, as is known, suffered very hard times. At that time it was again

Upper Silesia particularly, and those territories which were involved and

suffering under that problem, under that treatment. Further, the question of

disarmament was naturally one of the most important points of

Versailles.

December 15, 1920: Admission of Austria to the League of Nations.

April 24, 1921: In a plebiscite in the Tyrol, 145,302 vote for the Anschluss, 1,805 against.

May 18, 1921: In a plebiscite in the district of Salzburg, 98,546 vote for the Anschluss with 877 votes against.

September 2, 1921: The Permanent Court of International Justice comes into force.

April 28, 1925: Field Marshal von Hindenburg is elected President of the Reich on the death of Friedrich Ebert.

May 15, 1925 Gekaufter Aristokratischer Ausweis: Ribbentrop persuades his aunt Gertrud von Ribbentrop--whose late husband had been knighted--to adopt him, allowing him to add the aristocratic "von" to his name. In return for this rung on the social ladder, Ribbentrop is to make an established number of cash payments to his aunt. When he defaults on these payments, Aunt Gertrud sues, winning a full award.

September 8, 1926: Admission of Germany to the League of Nations. Germany is made a permanent Member of the Council.

March 29, 1930: Heinrich Brüning becomes the twelfth Chancellor of the Weimar Republic.

September 26, 1931: The Assembly of the League of Nations adopts a General Convention to improve the Means of Preventing War.

February 2, 1932: The two-year Conference for the Reduction and Limitation of Armaments opens in Geneva.

March 13, 1932: Hitler receives 30.1% of the vote in the Presidential elections: 11,339,446 votes. Hindenburg fails to win a majority. Goebbels writes in his diary: "We’re beaten; terrible outlook. Party circles badly depressed and dejected." A runoff election is scheduled for 19 April.

April 13, 1932: The SA and SS are banned by Chancellor Brüning after contingency plans for a Nazi coup are discovered.

April 19, 1932: Hindenburg is elected Reich President with 53.0 percent of the vote. Hitler's percentage improves from 30.1 to 36.8 percent of the electorate.

May 1, 1932 Dann ich Betrachtet: Ribbentrop joins the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP): Member Number 1,199,927. He quickly moves up the hierarchy.

From Ribbentrop's IMT Testimony: During the year 1931

and 1932, one noticed as a business man, which I was at the time, that in

practice the consequences of Versailles were such that German economic life

was becoming more and more prostrate. Then I looked around. At that time, I

was closely attached to the German People's Party and I saw how the parties

became always more and more numerous in Germany. I remember that in the end

we had something like 30 parties or more in Germany, that unemployment was

growing steadily, and that the government was losing the confidence of the

people more and more. From these years I clearly recollect the efforts made

by the then Chancellor Brüning, which were doubtlessly meant sincerely and

honestly but which nevertheless had no success. Other governments came, that

is well known. They, too, had no success.

The export trade in Germany no longer paid for itself. The gold reserves of

the Reichsbank dwindled, there was tax evasion, and no confidence at all in

the measures introduced by the government. That, roughly, was the picture

which I saw in Germany in the year 1930 and 1931. I saw then how strikes

increased, how discontented the people were, and how more and more

demonstrations took place on the streets and conditions became more and more

chaotic ... it was the denial of equality in all these spheres, the denial

of equal rights, which made me decide that year to take a greater part in

politics.

I would like to say here quite openly that at that time I often talked to

French and British friends, and of course it was already a well-known fact,

even then—after 1930 the NSDAP received over 100 seats in the

Reichstag—that here the natural will of the German people broke through to

resist this treatment, which after all meant nothing more than that they

wanted to live. At the time these friends of mine spoke to me about Adolf

Hitler, whom I did not know at the time, they asked me, 'What sort of a man

is Adolf Hitler? What will come of it? What is it?' I said to them frankly

at that time, "Give Germany a chance and you will not have Adolf Hitler. Do

not give her a chance, and Adolf Hitler will come into power." That was

approximately in 1930 or 1931. Germany was not given the chance, so on 30

January 1933 he came--the National Socialists seized power.

June 1932: The German government of von Papen lifts Brüning's ban on the SA and SS.

June 16, 1932 Lausanne Konferenz: The Lausanne conference begins as representatives from Great Britain, Germany, and France meet in Lausanne, Switzerland. Also: Reich Chancellor von Papen places a 1 month ban on the wearing of uniforms to political demonstrations.

From Ribbentrop's IMT Testimony: I must say that the

numerous business trips which in the years of 1920 to 1932 took me abroad

proved to me how endlessly difficult it was or would have to be under the

system which then existed to bring about a revision of the Versailles Treaty

by means of negotiations. In spite of that, I felt how from year to year the

circles grew in England and France which were convinced that somehow Germany

would have to be helped.

During those years, I established many contacts with men of the business

world, of public life, of art and science, particularly in universities in

England and France. I learned thereby to understand the attitude of the

English and the French. I want to say now that even shortly after Versailles

it was my conviction that a change of that treaty could be carried out only

through an understanding with France and Britain. I also believed that only

in this way could the international situation be improved and the very

considerable causes of conflict existing everywhere as consequences of the

first World War be removed. It was clear, therefore, that only by means of

an understanding with the Western Powers, with England and France, would a

revision of Versailles be possible.

Even then, I had the distinct feeling that only through such an

understanding could a permanent peace in Europe really be preserved. We

young officers had experienced too much at that time. And I am thinking of

the Free Corps men in Silesia and all those things in the Baltic, et cetera.

I should like to add, and say it quite openly, that right from the

beginning, from the first day in which I saw and read the Versailles Treaty,

I, as a German, felt it to be my duty to oppose it and to try to do

everything so that a better treaty could take its place. It was precisely

Hitler's opposition to Versailles that first brought me together with him

and the National Socialist Party.

From Ribbentrop's IMT Testimony: He (Hitler) saw in

France an enemy of Germany because of the entire policy which France had

pursued with regard to Germany since the end of World War I, and especially

because of the position which she took on questions of equality of rights.

This attitude of Hitler's found expression at the time in his book Mein

Kampf. I knew France well, since for a number of years I had had connections

there. At that time I told the Führer a great deal about France. It

interested him, and I noticed that he showed an increasing interest in

French matters in the year 1933. Then I brought him together with a number

of Frenchmen, and I believe some of these visits, and perhaps also some of

my descriptions of the attitude taken by many Frenchmen, and all of French

culture. ....

I acquainted the Führer with an argument which sprang from my deepest

conviction and my years of experience. It was a great wish of the Führer, as

is well known, to come to a definitive friendship and agreement with

England. At first the Führer treated this idea as something apart from

Franco-German politics. I believe that at that time I succeeded in

convincing the Führer that an understanding with England would be possible

only by way of an understanding with France as well. That made, as I still

remember very clearly from some of our conversations, a strong impression on

him. He told me then that I should continue this purely personal course of

mine for bringing about an understanding between Germany and France and that

I should continue to report to him about these things.

July, 1932: From a recorded campaign speech by Hitler :

July 30, 1932: German Chancellor von Papen:

July 31, 1932: The Nazi Party wins big in Reichstag elections, making it Germany’s largest political party; however, they still fall far short of a majority in the 608-member body. Goering, with backing from the Catholic Center Party, assumes the Presidency of the Reichstag.

August 13, 1932: Hindenburg rejects Hitler's demand to be appointed Chancellor. From minutes of the meeting kept by Otto Meissner, the Chief of the Presidential Chancellery:

The Reich President in reply said firmly that he must answer this demand with a clear, unyielding "No." He could not justify before God, before his conscience, or before the Fatherland the transfer of the whole authority of government to a single party, especially to a party that was biased against people who had different views from their own. There were a number of other reasons against it, upon which he did not wish to enlarge in detail, such as fear of increased unrest, the effect on foreign countries, etc. Herr Hitler repeated that any other solution was unacceptable to him. To this the Reich President replied: "So you will go into opposition?" Hitler: "I have now no alternative."

August 13, 1932: Ribbentrop meets Hitler for the first time.

From Ribbentrop's IMT Testimony: I saw Adolf Hitler for

the first time on 13 August 1932 at the Berghof. Since about 1930 or 1931 I

had known Count Helldorf in Berlin, whose name as a National Socialist is

known. He was a regimental comrade of mine in my squadron, and we went

through 4 years of war together. Through him I became acquainted with

National Socialism in Berlin for the first time. I had asked him at that

time to arrange a meeting with Hitler for me. He did so that time, as far as

I remember, through the mediation of Herr Rohm. I visited Adolf Hitler and

had a long discussion with him at that time, that is to say, Adolf Hitler

explained his ideas on the situation in the summer of 1932 to me.

I then saw him again in 1933--that has already been described here by Party

Member Göring—at my house at Dahlem which I placed at their disposal so

that I, on my part, should do everything possible to create a national

front. Adolf Hitler made a considerable impression on me even then. I

noticed particularly his blue eyes in his generally dark appearance, and

then, perhaps as outstanding, his detached, I should say reserved—not

unapproachable, but reserved—nature, and the manner in which he expressed

his thoughts. These thoughts and statements always had something final and

definite about them, and they appeared to come from his innermost self. I

had the impression that I was facing a man who knew what he wanted and who

had an unshakable will and who was a very strong personality.

I can summarize by saying that I left that meeting with Hitler convinced

that this man, if anyone, could save Germany from these great difficulties

and that distress which existed at the time. I need not go further into

detail about the events of that January. But I would like to tell about one

episode which happened in my house in Dahlem when the question arose whether

Hitler was to become Reich Chancellor or not. I know that at that time, I

believe, he was offered the Vice Chancellorship and I heard with what

enormous strength and conviction—if you like, also brutality and

hardness—he could state his opinion when he believed that obstacles might

appear which could lead to the rehabilitation and rescue of his people.

November 6, 1932: New elections in Germany fail to break a parliamentary deadlock. The National Socialists lose 34 seats, but not enough to crowd them out of their key position, for again the formation of a majority in the Reichstag from the Socialists to the extreme Right is possible only with Hitler; without him, no majority.

November 1932: Thirty-nine prominent German industrialists and businessmen petition Hindenburg to appoint Hitler as his new Chancellor.

December 3, 1932: General von Schleicher is appointed the fourteenth Chancellor of Germany under the Weimar Republic.

January 1, 1933: Hypnotist Erik Hanussen predicts Hitler will come to power on January 30, 1933. His prediction will be widely ridiculed in the German press.

January 15, 1933: Election in the small state of Lippe: the NSDAP gains 6,000 votes over the preceding November total but is still 3,000 votes short of its July number. This small success is spun into a triumph by skillful propaganda.

January 22, 1933: Ribbentrop, Papen, Goering, Meissner, and Oskar von Hindenburg (the President's son) hold discussions. Ribbentrop plays an important if not strikingly obvious part in the bringing about of the decisive meetings between the representatives of the President of the Reich and the heads of the NSDAP, who have prepared for the entry of the Nazis into power. These meetings take place in Ribbentrop's home in Berlin Dahlen.

January 28, 1933: Chancellor von Schleicher demands that President Hindenburg declare the Reichstag dissolved and grant him full powers. The President refuses and von Schleicher resigns as Chancellor. At noon, the Reich President instructs Papen to begin negotiations for the formation of a new government.

January 29, 1933: Hitler, enjoying coffee and cakes with some of his aides at the Kaiserhof, is joined by Goering who announces triumphantly that Hitler will be named Chancellor on the morrow. (Shirer)

January 30, 1933: Hitler is appointed as Chancellor. Ribbentrop, while given no position in the cabinet, becomes Hitler's unofficial advisor on foreign affairs.

From Ribbentrop's IMT Testimony: I acquainted the Führer with an argument which sprang from my deepest conviction and my years of experience. It was a great wish of the Führer, as is well known, to come to a definitive friendship and agreement with England. At first the Führer treated this idea as something apart from Franco-German politics. I believe that at that time I succeeded in convincing the Führer that an understanding with England would be possible only by way of an understanding with France as well. That made, as I still remember very clearly from some of our conversations, a strong impression on him. He told me then that I should continue this purely personal course of mine for bringing about an understanding between Germany and France and that I should continue to report to him about these things.

January 30, 1933: From a telegram to Hindenburg from Ludendorff:February 1, 1933: German Chancellor Adolf Hitler issues his first proclamation:

Unity is our tool. Therefore we now appeal to the German people to support this reconciliation. The National Government wishes to work and it will work. It did not ruin the German nation for fourteen years, but now it will lead the nation back to health. It is determined to make well in four years the ills of fourteen years. But the National Government cannot make the work of reconstruction dependent upon the approval of those who wrought destruction. The Marxist parties and their lackeys have had fourteen years to show what they can do. The result is a heap of ruins. Now, people of Germany, give us four years and then pass judgment.

February 1, 1933: Hitler obtains a decree from Hindenburg ordering dissolution of the Reichstag. New elections are called for March 5, 1933.

February 2, 1933: The Geneva Disarmament Conference resumes.

February 3, 1933: Hitler, addressing a group of German generals gathered at the Hammerstein-Equord house, proclaims an offensive against the Communists and Pacifists; announces that the Reichswehr will remain independent of the political parties; promises complete rearmament.

February 4, 1933: Hitler announces a new rule "for the protection of the German people" which allows the Nazis to forbid meetings of other political groups. He authorizes the Government to ban newspapers and rallies on the pretext that they are distributing false news to harm the State or defame the authorities and civil service.

February 15, 1933: Hitler speaks in Stuttgart:

February 24, 1933: The Stahlhelm (Steel Helmet), the SA and SS are officially granted auxiliary police status.

February 26, 1933: During a séance in Berlin, Eric Hanussen predicts that a great fire will soon strike a large building in the Capital. An eagle, he claims, will rise from the smoke and flames.

February 27, 1933: A huge fire destroys the Reichstag, the seat of German government.

February 28, 1933: The Prussian government announces that it has found communist publications stating that "Government buildings, museums, mansions and essential plants were to be burned down... . Women and children were to be sent in front of terrorist groups.... The burning of the Reichstag was to be the signal for a bloody insurrection and civil war.... It has been ascertained that today was to have seen throughout Germany terrorist acts against individual persons, against private property, and against the life and limb of the peaceful population, and also the beginning of general civil war."

February 28, 1933 Ausser den Gesetzlichen Grenzen: Hindenburg signs the "Decree for the Protection of the People and the State," which has been quickly drafted by Hitler and his aides. This emergency decree suspends the civil liberties granted by the Weimar Constitution by allowing the Nazis to put their political opponents in prison and establish concentration camps. Hermann Goering orders the arrest of 4,000 Communist functionaries. An excerpt from the Decree:

March 5, 1933: The last multiparty general election for the Reichstag draws 88.8% of eligible voters to the polls. The Combat Front coalition formed by the NSDAP and Hugenberg’s German National Peoples Party wins a 51.9% majority but falls short of the 2/3rds majority needed to amend the constitution.

March 7, 1933: Austrian Chancellor Dollfuss assumes dictatorial powers.

March 8, 1933 Millimetternich: Dollfuss suspends freedom of the press in Austria.

March 21, 1933 Potsdam Day: From the tomb of Frederick the Great at Potsdam, Hitler carefully stages an elaborate ceremonial opening of the first Reichstag of the Third Reich.

March 22, 1933: Dachau concentration camp opens near Munich, soon to be followed by Ravensbrück for women, Sachsenhausen near Berlin in northern Germany, and Buchenwald near Weimar in central Germany.

March 23 1933 Ermoeglichende Tat: In the evening session of the Reichstag, Monsignor Kaas announces that the Catholic Center Party, despite some certain misgivings, will vote for the Enabling Act. The Enabling Act is then passed by the Reichstag, transferring the power of legislation from the Reichstag to the cabinet. The Enabling Act gives Hitler the power to pass his own laws, independent of the President or anyone else, making Hitler more powerful than any Kaiser in German History.

March 23 1933: Hitler addresses the Reichstag:

April 1, 1933: A week into Hitler's dictatorship of Germany, Goebbels orders a boycott of Jewish shops, banks, offices and department stores.

April 7, 1933: The Nazi Civil Service Act is passed. It's a law that provides that all civil servants must be trustworthy as defined by Nazi standards and also must meet the Nazi racial requirements.

July 31, 1933: Six months after the Nazis assumption of power, the first concentration camps are full; 26,789 political prisoners are now in detention.

August 19, 1933: Mussolini meets with Austrian Chancellor Dollfuss at the Italian-Austrian border.

August 1933: After exchanging "Secret Letters" with Mussolini, Italy on this day guarantees Austria's independence. To Mussolini, Austria forms a desirable buffer zone against Nazi Germany that is in Italy's interest to maintain. Dollfuss, for his part, stresses the similarity of Hitler's and Stalin's regime, and is convinced that Austro-fascism under his reign and Italio-fascism under Mussolini can counter both national socialism and communism in Europe.

September 1933: Genetic Health Courts now being organized through out Germany will eventually order the sterilization of almost 400,000 German citizens: 32,268 during 1934; 73,174 in 1935; 63,547 in 1936. Note: In the U.S. 60,166 people were sterilized from 1907-1958.

September 12, 1933: Voting in a referendum, 89.9% of the voters approve Hitler's withdrawal from the League of Nations. This first one party election for the Reichstag sees 92.1% of the voters cast ballots. Also: Nazi Minister of the Interior Frick receives a letter of protest concerning the "Law for the Prevention of Genetically Diseased Offspring" from Cardinal Bertram.

October 11, 1933: US Ambassador Dodd criticizes the Nazi regime during an address to the American Chamber of Commerce in Berlin.

October 14, 1933: Germany withdraws from the Conference for the Reduction and Limitation of Armaments.

October 14, 1933: Hitler addresses the Reich by radio:

October 21, 1933: Germany gives notice of withdrawal from the League of Nations.

December 23, 1933: Pope Pius XI condemns the Nazi sterilization program.

January 30, 1934: Hitler addresses the Reichstag:

From The Face Of The Third Reich by Joachim C

Fest: The circumstances in which he found his way to Hitler in the

early 1930's are revealing in themselves. In response to a chance remark by

Hitler that he could not follow the foreign press because of his ignorance

of foreign languages, Ribbentrop, the wine and spirits importer was

recommended to him as a reader. Ribbentrop not only had a good knowledge of

languages but had also been the author of a political newsletter which was

sent to business contacts at home and abroad and which took a nationalist

and anti-Bolshevik line. Hitler accepted him, influenced not least by his

outward appearance as a man of the world. This was the start of a rapid rise

in a career of astounding incompetence.

For Ribbentrop, who shared Hitler's habit of indulging in great visions

expressed in endless monologues, it led into those realms where the

megalomaniac word loses its innocence and unexpectedly influences the

destinies of nations; where self-assertive coarseness brings the reputation,

not of a swashbuckler among neighbors and boon companions, but of a

disturber of the peace before the bar of history. Ribbentrop evidently never

grasped the difference between these two roles and confronted it during the

Nuremberg trial with that same strained mien which a lifelong intellectual

helplessness had forced him to adopt. He was condemned as the pot-house

politician whose bombastic utterances were suddenly fulfilled as by a

malevolent fairy, whose words, dictated by a hunger for self-importance,

suddenly became flesh and, even more, blood.

May 1, 1934: A new Austrian constitution is approved that makes all the decrees Dollfuss has already passed since March 1933 "legal." The new constitution sweeps away the last remains of democracy.

April 20, 1935: Ribbentrop is promoted to Obergruppenführer in the SS.

June 17, 1934: Vice-Chancellor von Papen speaks in Marburg:

From the sworn affidavit of Dr. Paul Otto Schmidt: Plans for annexation of Austria were a part of the Nazi program from the beginning. Italian opposition after the murder of Dollfuss temporarily forced a more careful approach to this problem, but the application of sanctions against Italy by the League, plus the rapid increase of German military strength, made safer the resumption of the Austrian program. When Goering visited Rome early in 1937 he declared that union of Austria and Germany was inevitable and could be expected sooner or later. Mussolini, hearing these words in German, remained silent, and protested only mildly when I translated them into French. The consummation of the Anschluss was essentially a Party matter, in which von Papen's role was to preserve smooth diplomatic relations on the surface while the Party used more devious ways of preparing conditions for the expected move. The speech delivered by Papen on 18 Feb. 1938, following the Berchtesgaden meeting, interpreted the Berchtesgaden agreement as the first step towards the establishment of a Central European Commonwealth under the leadership of Germany. This was generally recognized in the Foreign Office as a clear prophecy of a Greater Germany which would embrace Austria.

June 18, 1935: German Minister Plenipotentiary at Large Ribbentrop negotiates the Anglo-German Naval Agreement (AGNA). Ribbentrop, who possesses a certain elan and sense of audacity, issues Sir John Simon an ultimatum. He informs Simon that if Germany's terms are not accepted in their entirety, the German delegation will go home. Simon is angry with this demand and walks out of the talks. Much to everyone's surprise, the next day, the British accept Ribbentrop's demands and the AGNA is signed in London on this day. This diplomatic victory does much to increase Ribbentrop's prestige with Hitler.June 30, 1934 Blutbereinigung: The "Blood Purge" (Night of the Long Knives) occurs.

July 13, 1934: Hitler speaks before the Reichstag:

July 25, 1934: Austrian Chancellor Dollfuss is murdered by eight Austrian Nazis. A coup d'état fails, however, and order is soon restored. Kurt Alois Josef Johann Schuschnigg becomes Austria's new federal chancellor. At the age of 36, he is the youngest person to have ever held the position.

From the sworn affidavit of Dr. Paul Otto Schmidt: The attempted Putsch in Austria and the murder of Dollfuss on 25 July 1934 seriously disturbed the career personnel of the Foreign Office, because these events discredited Germany in the eyes of the world. It was common knowledge that the Putsch had been engineered by the Party, and the fact that the attempted Putsch followed so closely on the heels of the blood purge within Germany could not help but suggest the similarity of Nazi methods both in foreign and domestic policy. This concern over the repercussions of the attempted Putsch was soon heightened by a recognition of the fact that these episodes were of influence in leading to the Franco-Soviet Consultative Pact of 5 December 1934, a defensive arrangement, which was not heeded as a warning by the Nazis.

August 2, 1934: Hindenburg dies.August 19, 1934 Gleichschaltung: The German electorate approves Hitler's merging the two offices of Chancellor and President by 90% of the vote. Hitler is Führer und Reichskanzler.

September 18, 1934: Union of Soviet Socialist Republics is admitted into the League of Nations. The Assembly approves the Council's proposal that the Union should be made a permanent Member.

November 8, 1934: Hitler speaks in Munich:

January 13, 1935 Saar Volksabstimmung: 90.7 percent of Saar voters cast their ballot in favor of a return to Germany, 0.4 percent vote for union with France.

January 29, 1935: The American Senate refuses to ratify the accession of the United States to the Permanent Court of International justice.

February 1, 1935: Margarete Blank becomes Ribbentrop's personal secretary.

From the IMT testimony of Margarete Blank: I met him

(Ribbentrop) at the beginning of November 1934 in Berlin, when he was

delegate for disarmament questions. .... On 1 November 1934 I was engaged as

secretary in the Ribbentrop office. His personal secretary gave notice and,

as her successor did not turn up, von Ribbentrop asked me whether I was

willing to take the post. I said "yes" and became his personal secretary on

1 February 1935. ....

As far as I can judge, Herr von Ribbentrop always showed the greatest

admiration and veneration for Adolf Hitler. To enjoy the Führer's

confidence, to justify it by his conduct and work was his chief aim, to

which he devoted all his efforts. To achieve this aim no sacrifice was too

great. In carrying out the tasks set him by the Fuehrer he showed utter

disregard for his own person. When speaking of Hitler to his subordinates he

did so with the greatest admiration. Appreciation of his services by the

Fuehrer, as for instance the award of the Golden Party Badge of Honor, the

recognition of his accomplishments in a Reichstag speech, a letter on the

occasion of his fiftieth birthday, full of appreciation and praise, meant to

him the highest recompense for his unlimited devotion. ...

in cases of differences of opinion between himself and the Führer, Herr von

Ribbentrop subordinated his own opinion to that of the Führer. Once a

decision had been made by Adolf Hitler there was no more criticism

afterwards. Before his subordinates Herr von Ribbentrop presented the

Führer's views as if they were his own. If the Führer expressed his will, it

was always equivalent to a military order. .... I attribute it first of all

to Ribbentrop's view that the Führer was the only person capable of making

the right political decisions.

Secondly, I attribute it to the fact

that Herr von Ribbentrop, as the son of an officer and as a former officer

himself, having taken the oath of allegiance to the Fuehrer, felt himself

bound in loyalty and considered himself a soldier, so to say, who had to

carry out orders given him, and not to criticize or change them.

April 20, 1935: Ribbentrop is promoted to OberFührer in the SS.

May 1, 1935: Hitler speaks in Berlin:

May 2, 1935: A mutual assistance pact between France and the Soviet Union is signed.

From the sworn affidavit of Dr. Paul Otto Schmidt: The announcement in March of the establishment of a German Air Force and of the reintroduction of conscription was followed on 2 May 1935 by the conclusion of a mutual assistance pact between France and the Soviet Union. The career personnel of the Foreign Office regarded this as a further very serious warning as to the potential consequences of German foreign policy, but the Nazi leaders only stiffened their attitude towards the Western Powers, declaring that they were not going to be intimidated. At this time, the career officials at least expressed their reservations to the Foreign Minister, Neurath. I do not know whether or not Neurath in turn related these expressions of concern to Hitler.

June 18, 1935: The Anglo-German Naval Agreement, a bilateral agreement between the United Kingdom and the German Reich regulating the size of the Kriegsmarine in relation to the Royal Navy, is signed. This is an enormous victory for Ribbentrop and Hitler, and the first large nail in the coffin he is constructing to contain the remains of Treaty of Versailles.June 18, 1935: Ribbentrop is promoted to Brigadeführer in the SS.

August, 1935 Wehchaftmachung: Hitler begins rearmament in earnest.

September 15, 1935: Reich Citizenship Law:

ARTICLE I A subject of the State is a person who belongs to the protective union of the German Reich, and who, therefore, has particular obligations towards the Reich. The status of the subject is acquired in accordance with the provisions of the Reich and State Law of Citizenship.

ARTICLE II A citizen of the Reich is only that subject who is of German or kindred blood, and who, through his conduct, shows that he is both desirous and fit to serve faithfully the German people and Reich. The right to citizenship is acquired by the granting of Reich citizenship papers. Only the citizen of the Reich enjoys full political rights in accordance with the provisions of the Laws.

ARTICLE III The Reich Minister of the Interior, in conjunction with the Deputy of the Führer, will issue the necessary legal and administrative decrees for the carrying out and supplementing of this law.

October 21, 1935: Germany ceases to be a Member of the League of Nations.

February 21, 1936: Germany protests against the French-Soviet Pact of Mutual Assistance, saying it violates the Covenant of the League of Nations, as well as the Locarno Treaties.

From the sworn affidavit of Dr. Paul Otto Schmidt: The re-entry of the German military forces into the Rhineland was preceded by Nazi diplomatic preparation in February. A German communiqué of 21 February 1936 reaffirmed that the French-Soviet Pact of Mutual Assistance was incompatible with the Locarno Treaties and the Covenant of the League. On the same day Hitler argued in an interview that no real grounds existed for conflict between Germany and France. Considered against the background statements in Mein Kampf, offensive to France, the circumstances were such as to suggest that the stage was being set for justifying some future act. I do not know how far in advance the march into the Rhineland was decided upon. I personally knew about it and discussed it approximately 2 or 3 weeks before it occurred. Considerable fear had been expressed, particularly in military circles, concerning the risks of this undertaking. Similar fears were felt by many in the Foreign Office. It was common knowledge in the Foreign Office, however, that Neurath was the only person in government circles, consulted by Hitler, who felt confident that the Rhineland could be remilitarized without armed opposition from Britain and France. Neurath's position throughout this period was one which would induce Hitler to have more faith in Neurath than in the general run of 'old school' diplomats whom Hitler tended to hold in disrespect.

March 8, 1936: Germany denounces the treaty of Locarno.March 20, 1936: Hitler speaks in Hamburg:

July 11, 1936: The Berchtesgaden Agreement regarding the maintenance of Austrian sovereignty is negotiated.

August 1936: Hitler appoints Ribbentrop ambassador to London. His main objective will be to persuade the British government not to get involved in Germany territorial disputes and to work together against the the communist government in the Soviet Union.

From The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich by William L. Shirer: Incompetent and lazy, vain as a peacock, arrogant and without humor, Ribbentrop was the worst possible choice for such a post (ambassador to London), as Göring realized. "When I criticized Ribbentrop's qualifications to handle British problems," he later declared, "the Führer pointed out to me that Ribbentrop knew 'Lord So and So' and 'Minister So and So.' To which I replied: Yes, but the difficulty is that they know Ribbentrop."

From the IMT testimony of Margarete Blank: Von Ribbentrop, in the summer of 1936, asked the Führer to send him as ambassador to England. The Naval Agreement of 1935 was only a first step. Subsequently an air pact was contemplated, but, for reasons unknown to me, was not concluded. .... From numerous statements by Ribbentrop I know he was of the opinion that England still adhered to her traditional balance of power policy. In this his ideas were opposed to those of the Fuehrer, who was of the opinion that with the development of Russia a factor had arisen in the East which necessitated a revision of the old balance of power policy--in other words, that England had a vital interest in the steadily increasing strength of Germany. From Ribbentrop's attitude it could be inferred that he expected that in the Polish crisis the English guarantee for Poland would be honored.

January 30, 1937: Hitler:February 5, 1937: Ribbentrop presents his credentials to George VI, but the British are outraged when he snaps off a Hitler salute to the King. He also upsets the British government by posting Schutz Staffeinel (SS) guards outside the German Embassy and by flying swastika flags on official embassy cars.

From the IMT testimony of General Erhard Milch: I had gained the impression in England that von Ribbentrop was not persona grata. I was of the opinion that another man should be sent to England to bring about mutual understanding as to policy, in accordance with the wish so often expressed by Hitler.

May 1, 1937: Hitler's Germany is outraged when an Austrian official in the small hamlet of Pinkafeld hauls down a flag of the German Reich. Hitler speaks in Berlin:November 19, 1937: Lord Halifax meets with Adolf Hitler in Berchtesgaden:

From the IMT testimony of Dr. Paul Otto Schmidt (German

Foreign Office Interpreter): I had been working in the Foreign Office as

interpreter for conferences since 1923, and in this capacity I interpreted

for all foreign ministers, from Stresemann to von Ribbentrop, as well as for

a number of German Reich Chancellors such as Hermann Muller, Marx, Brüning,

Hitler, and for other cabinet members and delegates who represented Germany

at international conferences. In other words, I participated as interpreter

in all international conferences at which Germany was represented since

1923. ....

First I must say that at the Obersalzberg the conversation with Lord Halifax

had taken a very unsatisfactory turn. The two partners could in no way come

to an understanding, but in the conversation with Goering the atmosphere

improved. The same points were dealt with as at Obersalzberg, the subjects

which were in the foreground at the time, namely, the Anschluss, the Sudeten

question, and finally the questions of the Polish Corridor and Danzig. At

Obersalzberg Hitler had treated these matters rather uncompromisingly, and

he had demanded more or less that a solution as he conceived it be accepted

by England, whereas Goering in his discussions always attached importance to

the fact or always stressed that his idea was a peaceful solution, that is

to say, a solution through negotiation, and that everything should be done

in this direction, and that he also believed that such a solution could be

reached for all three questions if the negotiations were properly conducted.

From the sworn affidavit of Dr. Paul Otto Schmidt: Whatever

success and position I have enjoyed in the Foreign Office I owe to the fact

that I made it my business at all times to possess thorough familiarity with

the subject matter under discussion, and I endeavored to achieve intimate

knowledge of the mentality of Hitler and the other leaders. Throughout the

Hitler Regime I constantly endeavored to keep myself apprised as to what was

going on in the Foreign Office and in related organizations, and I enjoyed

such a position that it was possible to have ready access to key officials

and to key personnel in their offices. ....

The general objectives of the Nazi leadership were apparent from the start,

namely, the domination of the European Continent, to be achieved, first, by

the incorporation of all German-speaking groups in the Reich, and secondly,

by territorial expansion under the slogan of Lebensraum. The

execution of these basic objectives, however, seemed to be characterized by

improvisation. Each succeeding step apparently was carried out as each new

situation arose, but all consistent with the ultimate objectives mentioned

above.

From the IMT testimony of Margarete Blank: Although I

was his personal secretary for 10 years, I hardly ever saw him in a

communicative mood. His time and thoughts were so completely occupied by his

work, to which he devoted himself wholeheartedly, that there was no room for

anything private. Apart from his wife and children there was nobody with

whom Von Ribbentrop was on terms of close friendship. This, however, did not

prevent him from having the welfare of his subordinates at heart and from

showing them generosity, particularly in time of need. ....

Von Ribbentrop never discussed such differences (with Hitler) with his

subordinates, but I do remember distinctly that there were times when such

differences surely did exist. At such times the Führer refused for weeks to

receive Herr von Ribbentrop. Ribbentrop suffered physically and mentally

under such a state of affairs. .... Ribbentrop often used the phrase that he

was only the minister responsible for carrying out the Führer's foreign

policy. By this he meant that, in formulating his policy, he was not

independent. In addition, even in carrying out the directives given him by

the Führer, he was to a large extent bound by instructions from Hitler.

Thus, for instance, the daily reports of a purely informative nature

transmitted by the liaison officer, Ambassador Hewel, between the Minister

for Foreign Affairs and the Führer were often accompanied by requests for

the Fuehrer's decision on individual questions and by draft telegrams

containing instructions to the heads of missions abroad. ....

The Führer saw in the Foreign Office a body of ossified red-tape civil

servants, more or less untouched by National Socialism. I gathered from men

of his entourage, that he often made fun of the Foreign Office. He

considered it to be the home of reaction and defeatism. .... When taking

over the Foreign Office in February 1938, Herr von Ribbentrop intended to

carry out a thorough reshuffle of the entire German diplomatic service. He

also intended to make basic changes in the training of young diplomats.

These plans did not go beyond the initial stage because of the war. In the

course of the war they were taken up again when the, question of new blood

for the Foreign Office became acute. Ribbentrop's anxiety to counteract the

Fuehrer's animosity towards the Foreign Office led him to fill some of the

posts of heads of missions abroad, not with professional diplomats, but with

tried SA and SS leaders.

February 12, 1938: The Austro-German Crisis begins as Hitler meets with Austrian Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg at Berchtesgaden.

From Ribbentrop's IMT Testimony: I do not consider the

Anschluss as an act of aggression... I consider it the realization of the

mutual purpose of both nations involved. They had always wished to be

together and the government before Adolf Hitler had already striven for

it....it was no aggression in that sense, but a union in accordance with the

right of self-determination of nations, as laid down in 1919 by the

President of the United States, Wilson. The annexation of the Sudetenland

was sanctioned by an agreement of four great powers in Munich. ....

I consider, according to the words of the Fuehrer, and I believe he was

right, that it was a necessity resulting from Germany's geographical

position. This position meant that the remaining part of Czechoslovakia, the

part which still existed, could always be used as a kind of aircraft-carrier

for attacks against Germany. The Führer therefore considered himself obliged

to occupy the territory of Bohemia and Moravia, in order to protect the

German Reich against air attack—the air journey from Prague to Berlin took

only half an hour. The Führer told me at the time that in view of the fact

that United States had declared the entire Western Hemisphere as its

particular sphere of interest, that Russia was a powerful country with

gigantic territories, and that England embraced the entire globe, Germany

would be perfectly justified in considering so small a space as her own

sphere of interest.

February 14, 1938 Jodl's Diary:

February 20, 1938: In a speech aimed specifically at Czechoslovakia, Chancellor Adolf Hitler proclaims that the German government vows to protect German minorities outside of the Reich.

February 20, 1938: British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden resigns in protest of Chamberlain's policy of appeasement with Italy and Germany.

March 4, 1938: From a letter from Ribbentrop to Keitel:

March 9, 1938: Austrian Chancellor Schuschnigg schedules a plebiscite on the independence of Austria for 13 March. The question is to be: Are you for an independent and social, a Christian, German and united Austria?

March 10, 1938 Jodl's Diary:

He drives to the Reichskanzlei at 10 o'clock. I follow at 10:15, according to the wish of General v. Viebahn, to give him the old draft. Prepare case Otto. 1300 hours: General K informs Chief of Operational Staff (and) Admiral Canaris. Ribbentrop is being detained in London. Neurath takes over the Foreign Office. Führer wants to transmit ultimatum to the Austrian Cabinet. A personal letter is dispatched to Mussolini and the reasons are developed which force the Führer to take action. 1830 hours: Mobilization order is given to the Command of the 8th Army (Corps Area 3) 7th and 13th Army Corps; without reserve Army.

March 11, 1938: From Austrian Chancellor Schuschnigg's farewell speech:

March 12, 1938 Anschluss: Seyss-Inquart "invites" German troops to occupy Austria.

From the IMT testimony of Margarete Blank: At the time of the German march into Austria, Ambassador von Ribbentrop, who in February had been appointed Foreign Minister, was in London on his farewell visit. There he heard to his surprise of the Anschluss of Austria. He himself had had a different idea of a solution of the Austria question, namely an economic union.

March 12, 1938 Anschluss: The German Army marches unopposed into Vienna.March 14, 1938: The Czechoslovak government receives assurances from Hitler's government of the German desire to improve relations between the two states.

March 16-19, 1938: As most of Europe is preoccupied with the German absorption of Austria, the Polish government issues a series of demands to the Lithuanians. Faced with the threat of war, the Lithuanian government immediately agrees to all of the Polish demands, including recognition of the status quo in eastern Europe. The Lithuanian capitulation prevents the crisis from escalating.

March 17, 1938: From a letter—captured in the German Foreign Office files—from Konrad Henlein to Ribbentrop:

March 22-25, 1938: German political parties which had joined the Hodza ministry in Czechoslovakia, and the members of the German Activists withdraw from the government. Sudeten Germans are unmoved when Prime Minister Milan Hodza responds by announcing a new Nationality Statute designed to protect Czechoslovakian minorities.

March 25, 1938: Hitler speaks in Koenigsberg:

March 26, 1939: From a letter by Neville Chamberlain to a friend:

March 29, 1938: From captured German Foreign Office notes—initialed by Ribbentrop—of a conference in the Foreign Office in Berlin:

The aim of the negotiations to be carried out by the Sudeten German Party with the Czechoslovakian Government is finally this: To avoid entry into the Government by the extension and gradual specification of the demands to be made. It must be emphasized clearly in the negotiations that the Sudeten German Party alone is the party to the negotiations with the Czechoslovakian Government, not the Reich Cabinet. The Reich Cabinet itself must refuse to appear toward the government in Prague or toward London and Paris as the advocate or pacemaker of the Sudeten German demands. It is a self-evident prerequisite that during the impending discussion with the Czechoslovak Government the Sudeten Germans should be firmly controlled by Konrad Henlein, should maintain quiet and discipline, and should avoid indiscretions. The assurances already given by Konrad Henlein in this connection were satisfactory.

Following these general explanations of the Reichsminister, the demands of the Sudeten German Party from the Czechoslovak Government, as contained in the enclosure, were discussed and approved in principle. For further co-operation, Konrad Henlein was instructed to keep in the closest possible touch with the Reichsminister and the head of the Central Office for Racial Germans, as well as the German Minister in Prague, as the local representative of the Foreign Minister. The task of the German Minister in Prague would be to support the demand of the Sudeten German Party as reasonable--not officially, but in more private talks with the Czechoslovak politicians, without exerting any direct influence on the extent of the demands of the Party.

In conclusion, there was a discussion whether it would be useful if the Sudeten German Party would co-operate with other minorities in Czechoslovakia, especially with the Slovaks. The Foreign Minister decided that the Party should have the discretion to keep a loose contact with other minority groups if the adoption of a parallel course by them might appear appropriate.

April 10, 1938: In a national plebiscite, Austrian voters register 99.75% in favor of union with Germany: Austria becomes part of the Reich as a new state, divided into seven Gaue (states). Austria withdraws as a member state from the League of Nations because of the republic's incorporation into Germany.

August 19, 1938: From a German Foreign Office memorandum:

Under these conditions the Bureau Burger is no longer able to get along with the monthly allowance of 3,000 marks if it is to do everything required. Therefore Herr Burger has applied to this office for an increase of this amount from 3,000 marks to 5,500 marks monthly. In view of the considerable increase in the business transacted by the bureau, and of the importance which marks the activity of the bureau in regard to the co-operation with the Foreign Office, this desire deserves the strongest support. Herewith submitted to the personnel department with a request for approval. Increase of payments with retroactive effect from 1 August is requested.

August 21-26, 1938 Jodl's diary:

August 21-26, 1938: A series of the conversations between Hitler and Ribbentrop and a Hungarian Delegation consisting of Horthy, Imredy, and Kanya take place aboard the SS Patria. In this conference Ribbentrop inquires about the Hungarian attitude in the event of a German attack on Czechoslovakia and suggests that such an attack would prove to be a good opportunity for Hungary. The Hungarians, with the exception of Horthy, who wish to put the Hungarian intention to participate on record, prove reluctant to commit themselves. Thereupon Hitler emphasizes Ribbentrop's statement and declares that whoever wants to join the meal will have to participate in the cooking as well.

August 23, 1938: From a captured German Foreign Office account signed by Von Weizsaecker:

Von Ribbentrop inquired what Hungary's attitude would be if the Führer would carry out his decision to answer a new Czech provocation by force. The reply of the Hungarians presented two kinds of obstacles: The Yugoslavian neutrality must be assured if Hungary marches towards the north and perhaps the east; moreover, the Hungarian rearmament had only been started and one to two more years time for its development should be allowed.

Von Ribbentrop then explained to the Hungarians that the Yugoslavs would not dare to march while they were between the pincers of the Axis Powers. Romania alone would therefore not move. England and France would also remain tranquil. England would not recklessly risk her empire. She knew our newly acquired power. In reference to time, however, for the above-mentioned situation, nothing definite could be predicted since it would depend on Czech provocation. Von Ribbentrop repeated that, '"Whoever desires revision must exploit the good opportunity and participate."

The Hungarian reply thus remained a conditional one. Upon the question of vgon Ribbentrop as to what purpose the desired General Staff conferences were to have, not much more was brought forward than the Hungarian desire of a mutual inventory of military material and preparedness for the Czech conflict. The clear political basis for such a conflict—the time of a Hungarian intervention—was not obtained.

In the meantime, more positive language was used by Von Horthy in his talk with the Führer. He wished not to hide his doubts with regard to the English attitude, but he wished to put on record Hungary's intention to participate. The Hungarian Ministers were, and remained even later, more skeptical since they feel more strongly about the immediate danger for Hungary with its unprotected flanks.

When von Imredy had a discussion with the Führer in the afternoon he was very relieved when the Führer explained to him that in regard to the situation in question he demanded nothing of Hungary. He himself would not know the time. Whoever wanted to join the meal would have to participate in the cooking as well. Should Hungary wish conferences of the General Staffs he would have no objections.

August 23, 1938: From a German Foreign Office note on a conversation with Ambassador Attolico signed "R" for Ribbentrop:

August 25, 1938: From another German Foreign Office note:

August 27, 1938: From yet another German Foreign Office note:

September 6, 1938 Jodl's Diary:

September 16, 1938: From a telegram from the Foreign Office in Berlin to the Legation in Prague:

September 17, 1938: From the Reich Foreign Office, Most urgent:

September 24, 1938: To the Reich Foreign Office:

September 28, 1938: Hitler speaks in Berlin:

September 29, 1938 Muenchen Konferenz: The Munich Conference concludes.

From Ribbentrop's IMT Testimony: Then came the Munich

conference. I take it I need not go into the details of this conference; I

should like only to describe briefly the results of it. The Führer

explained to the statesmen, with the aid of a map, the necessity, as he saw

it, of annexing a particular part of the Sudetenland to the German Reich to

reach final satisfaction. A discussion arose; Mussolini, the Italian Chief

of Government, agreed in general with Hitler's ideas. The English Prime

Minister made at first certain reservations and also mentioned that perhaps

the details might be discussed with the Czechs, with Prague.

Daladier, the French Minister, said, as far as I recall, that he thought

that since this problem had already been broached, the four great powers

should make a decision here and now. In the end this opinion was shared by

all the four statesmen; as a result the Munich Agreement was drawn up

providing that the Sudetenland should be annexed to Germany as outlined on

the maps that were on hand. The Führer was very pleased and happy about

this solution, and, with regard to other versions of this matter which I

have heard during the Trial here, I should like to emphasize here once more

particularly that I also was happy. We all were extremely happy that in this

way in this form the matter had been solved.

From Ribbentrop's IMT Testimony: The Munich Agreement is

well known. Its contents were the following: Germany and England should

never again wage war; the naval agreement on the ratio of 100 to 35 was to

be permanent and, in important matters, consultations were to be resorted

to. Through this agreement the atmosphere between Germany and England was

undoubtedly cleared up to a certain degree. It was to be expected that the

success of this pact would lead to a final understanding. The disappointment

was great when, a few days after Munich, rearmament at any cost was

announced in England.

Then England started on a policy of alliance and close relationship with

France. In November 1938 trade policy measures were taken against Germany,

and in December 1938 the British Colonial Secretary made a speech in which a

"no" was put to any revision of the colonial question. Contact with the

United States of America was also established. Our reports of that period,

as I. remember them, showed an increased--I should like to say--stiffening

of the English attitude toward Germany; and the impression was created in

Germany of a policy which practically aimed at the encirclement of

Germany.

From Ribbentrop's IMT Testimony: There had always been

the minority problem in Poland, which had caused great difficulties. Despite

the agreement of 1934, this situation had not changed. In the year 1938 the

'de-Germanization' measures against German minorities were continued by

Poland. Hitler wished to reach some clear settlement with Poland, as well as

with other countries. Therefore he charged me, I believe during October

1938, to discuss with the Polish ambassador a final clarification of the

problems existing between Germany and Poland... There were two questions:

One, the minority problem, was the most burning one; the second problem was

the question of Danzig and the Corridor, that is to say, of a connection

with East Prussia. ....

It is clear that these two questions were the problems that had caused the

greatest difficulties since Versailles. Hitler had to solve these problems

sooner or later one way or another. I shared this point of view. Danzig was

exposed to continual pressure by the Poles; they wanted to "Polandize"

Danzig more and more and by October of 1938 from 800,000 to a million

Germans, I believe, had been expelled from the Corridor or had returned to

Germany. ....

The Polish Ambassador was reticent at first. He did not commit himself, nor

could he do so. I naturally approached him with the problem in such a way

that he could discuss it at ease with his government, and did not request,

so to speak, a definitive answer from him. He said that of course he saw

certain difficulties with reference to Danzig, and also a corridor to East

Prussia was a question which required much consideration. He was very

reticent, and the discussion ended with his promise to communicate my

statements, made on behalf of the German Government, to his government, and

to give me an answer in the near future.

November 11, 1938: The US ambassador to Germany is recalled.

From Ribbentrop's IMT Testimony: We never really found

out the details, and we very much regretted it, as it forced us to recall

our own Ambassador in Washington, at least to call him back to make a

report. It is, however, evident that this measure was determined by the

whole attitude of the United States. Many incidents took place about that

time which gradually convinced the Fuehrer that sooner or later they would

bring the United States into the war against us. Permit me to mention a few

examples. President Roosevelt's attitude was defined for the first time in

the 'quarantine speech' which he made in 1937. The press then started an

energetic campaign.

After the ambassador was recalled the situation

grew more critical and the effect began to make itself felt in every sphere

of German-American relations. I believe that many documents dealing with the

subject have been published in the meantime and that a number of these have

been submitted by the Defense, dealing, for instance, with the attitude

adopted by certain United States diplomats at the time of the Polish crisis;

the cash-and-carry clause was then introduced which could benefit only

Germany's enemies; the ceding of destroyers to England; the so-called

Lend-Lease Bill later on; and in other fields the further advance of the

United States towards Europe: The occupation of Greenland, Iceland, on the

African Continent, et cetera; the aid given to Soviet Russia after the

outbreak of this war. All these measures strengthened the Fuehrer's

conviction that sooner or later he would certainly have to reckon with a war

against America. There is no doubt that the Führer did not, in the first

instance, want such a war; and I may say that I myself, as I think you will

see from many of the documents submitted by the Prosecution, again and again

did everything I could, in the diplomatic field, to keep the United States

out of this war.

December 6, 1938: Ribbentrop visits Paris, where he and the French foreign minister, Georges Bonnet, sign a grand-sounding but largely meaningless Declaration of Franco-German Friendship. Ribbentrop is later to claim that Bonnet told him that France recognized Eastern Europe as being within Germany's sphere of influence.

January 21, 1939: From the minutes of Hitler's reception of the Czech Foreign Affairs Minister, Chvalkovsky:

The Führer thanked him for his statements. The foreign policy of a people is determined by its home policy. It is quite impossible to carry out a foreign policy of type 'A' and at the same time a home policy of type 'B.' It could succeed only for a short time. From the very beginning the development of events in Czechoslovakia was bound to lead to a catastrophe. This catastrophe had been averted thanks to the moderate conduct of Germany. Had Germany not followed the National Socialist principles which do not permit of territorial annexations the fate of Czechoslovakia would have followed another course. Whatever remains today of Czechoslovakia has been rescued not by Benes, but by the National Socialist tendencies. ....

For instance, the strength of the Dutch and Danish armies rests not in themselves alone but in realizing the fact that the whole world was convinced of the absolute neutrality of these states. When war broke out, it was well known that the problem of neutrality was one of extreme importance to these countries. The case of Belgium was somewhat different, as that country had an agreement with the French General Staff. In this particular case Germany was compelled to forestall possible eventualities. These small countries were defended not by their armies but by the trust shown in their neutrality. ....

Chvalkovsky, backed by Mastny, again spoke about the situation in Czechoslovakia and about the healthy farmers there. Before the crisis, the people did not know what to expect of Germany. But when they saw that they would not be exterminated and that the Germans wished only to lead their people back home, they heaved a sigh of relief. .... World propaganda, against which the Fuehrer had been struggling for so long a time, was now focused on tiny Czechoslovakia. Chvalkovsky begged the Führer to address, from time to time, a few kind words to the Czech people. That might work miracles. The Führer is unaware of the great value attached to his words by the Czech people. If he would only openly declare that he intended to collaborate with the Czech people--and with the people, themselves, not with the Minister for Foreign Affairs--all foreign propaganda would be utterly defeated. The Fuehrer concluded the conversation by expressing his belief in a promising future.

January 25, 1939: From a speech by Ribbentrop in Warsaw:

January 25, 1939: Polish Foreign Minister Beck visits Hitler at Berchtesgaden.

From Ribbentrop's IMT Testimony: I was present at that

conversation. The result was that Adolf Hitler informed Beck, once more in

detail, of his desire for good German-Polish relations. He said that a

completely new solution would have to be found in regard to Danzig, and that

a corridor to East Prussia should not give rise to insurmountable

difficulties. During this conversation Mr. Beck was rather receptive. He

told the Fuehrer that naturally the question of Danzig was difficult because

of the mouth of the Vistula, but he would think the problem over in all its

details. He did not at all refuse to discuss this problem, but rather he

pointed out the difficulties which, due to the Polish attitude, confronted a

solution of the problem. ....

After the meeting at Berchtesgaden with the Fuehrer, I had another lengthy

conversation with Beck in Munich. During this conversation Beck explained to

me again that the problem was very difficult, but that he would do

everything he could; he would speak to his governmental colleagues, and one

would have to find a solution of some kind. On this occasion we agreed that

I would pay him a return visit in Warsaw.

During this visit we also spoke about the minority question, about Danzig

and the Corridor. During this conversation the matter did not progress

either; Mr. Beck rather repeated the arguments why it was difficult. I told

him that it was simply impossible to leave this problem, the way it was

between Germany and Poland. I pointed out the great difficulties encountered

by the German minorities and the undignified situation, as I should like to

put it, that is, the always undignified difficulties confronting Germans who

wanted to travel to East Prussia. Beck promised to help in the minority

question, and also to re-examine the other questions. Then, on the following

day, I spoke briefly with Marshal Smygly-Rydz, but this conversation did not

lead to anything.

These examples from reports from authorities abroad can, if desired, be amplified. They confirm the correctness of the expectation that criticism of the measures for excluding Jews from German Lebensraum, which were misunderstood in many countries for lack of evidence, would be only temporary and would swing in the other direction the moment the population saw with its own eyes and thus learned what the Jewish danger was to them. The poorer and therefore the more burdensome the immigrant Jew is to the country absorbing him, the stronger this country will react and the more desirable is this effect in the interest of German propaganda. The object of this German action is to be a future international solution of the Jewish question, dictated not by false compassion for the "United Religious Jewish Minority" but by the full consciousness of all peoples of the danger which it represents to the racial composition of the nations.

From Ribbentrop's IMT Testimony: I saw this circular

here for the first time. Here are the facts: There was a section in the

Foreign Office which was concerned with Party matters and questions of

ideology. That department undoubtedly co-operated with the competent

departments of the Party. That was not the Foreign Office itself. I saw the

circular here. It seems to me that it is on the same lines as most of the

circulars issued at the time for the information and training of officials,

and so on. It even might possibly have gone through my office, but I think

that the fact that it was signed by a section chief and not by myself or by

the state secretary, should prove that I did not consider the circular very

important even if I did see it.

Even if it did go through my office or pass me in some other way, I

certainly did not read it because in principle I did not read such long

documents, but asked my assistants to give me a short summary of the