June 22, 1941: Operation Barbarossa (Unternehmen Barbarossa)—Nazi Germany's stunning invasion of the Soviet Union—begins as 4.5 million troops of the Axis powers invade the USSR along an 1,800 mile front.

From Keitel's IMT testimony: I have to say too that the intelligence service of the OKW, Admiral Canaris, placed at my disposal or at the Army's disposal very little material because the Russian area was closely sealed against German intelligence. In other words, there were gaps up to a certain point ... Halder reported that there were 150 divisions of the Soviet Union deployed along the line of demarcation. Then there were aerial photographs of a large number of airdromes. In short, there was a degree of preparedness on the part of Soviet Russia, which could at any time lead to military action. Only the actual fighting later made it clear just how far the enemy had been prepared. I must say, that we fully realized all these things only during the actual attack.

July 2, 1941: Heydrich sends an order setting out the verbal instructions to be given to the Einsatzgruppen (Operational Groups - paramilitary death squads) in the occupied Soviet territories:July 3, 1941: Stalin addresses the USSR by way of radio:

July 10, 1941: From Ribbentrop to the German Ambassador in Tokyo:

From Ribbentrop's IMT testimony: The war against Russia had started, and I tried at the time—the Führer held the same view—to get Japan into the war against Russia in order to end the war with Russia as soon as possible. That was the meaning of that telegram.

July 10, 1941: Ostrov and Pskov are captured and the German 18th Army reaches Narva and Kingisepp. This has the effect of creating siege positions from the Gulf of Finland to Lake Ladoga, with the eventual aim of isolating Leningrad from all directions.July 16, 1941: From a top-secret memorandum (prepared by Martin Bormann) of a conference at the Führer's headquarters concerning the war in the East attended by Hitler, Lammers, Göring, Keitel, Rosenberg, and Bormann:

Our conduct therefore ought to be:

1) To do nothing which might obstruct the final settlement, but to prepare for it only in secret;

2) To emphasize that we are liberators.

In particular: The Crimea has to be evacuated by all foreigners and to be settled by Germans only. In the same way the former Austrian part of Galicia will become Reich Territory. Our present relations with Romania are good, but nobody knows what they will be at any future time. This we have to consider, and we have to draw our frontiers accordingly. One ought not to be dependent on the good will of other people. We have to plan our relations with Romania in accordance with this principle. On principle, we have now to face the task of cutting up the giant cake according to our needs, in order to be able: First, to dominate it; second, to administer it; and third, to exploit it. The Russians have now ordered partisan warfare behind our front. This partisan war again has some advantage for us; it enables us to eradicate everyone who opposes us.

Principles: Never again must it be possible to create a military power west of the Urals, even if we have to wage war for a hundred years in order to attain this goal. Every successor of the Führer should know security for the Reich exists only if there are no foreign military forces west of the Urals. It is Germany who undertakes the protection of this area against all possible dangers. Our iron principle is and has to remain: We must never permit anybody but the Germans to carry arms...

The Führer emphasizes that the entire Baltic country will have to be incorporated into Germany. At the same time, the Crimea, including a considerable hinterland (situated north of the Crimea), should become Reich territory; the hinterland should be as large as possible. Rosenberg objects to this because of the Ukrainians living there. Note by Bormann: (Incidentally: It occurred to me several times that Rosenberg has a soft spot for the Ukrainians; thus he desires to aggrandize the former Ukraine to a considerable extent.) The Führer emphasizes furthermore that the Volga colony, too, will have to become Reich territory, also the district around Baku; the latter will have to become a German concession (military colony).

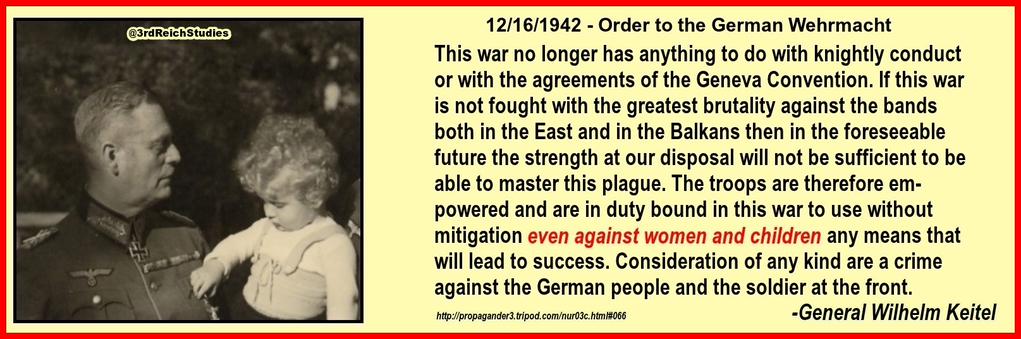

July 27, 1941: From an order signed by Keitel:

a) All of files up to the rank of 'general commands' inclusive b) group commands of the armored troops c) army commands and offices of equal rank, if there is an inevitable danger that they might fall into the hands of unauthorized persons. The validity of the decree is not affected by the destruction of the copies. In accordance with Paragraph III, it remains the personal responsibility of the commanding officers to see to it that the offices and legal advisers are instructed in time and that only the sentences are confirmed which correspond to the political intentions of the Supreme Command. This order will be destroyed together with the copies of the Fuehrer's decree.

August 4, 1941 Stalin to FDR:

August 14, 1941: Churchill and FDR release a joint declaration; the Atlantic Charter:

August 16, 1941: Joseph Stalin, acting as People's Commissar of Defense, releases Order No. 270, prohibiting any Soviet soldier from surrendering: “There are no Russian prisoners of war, only traitors.” The order demands anyone deserting or surrendering to be killed on the spot, and subjects their families to arrest and their wives to be sent to labor camps.

August 24, 1941: Finnish President Ryti, who had declared in numerous speeches to the Finnish Parliament that the aim of the war is to gain more territories in the east and create a 'Greater Finland,' will later declare:

August 30, 1941: The last rail connection to Leningrad is severed.

August 31 1941: Finnish military leader Mannerheim orders a stop to the offensive when the Finnish advance reaches the 1939 border with the USSR.

September 8 1941: German forces succeed in surrounding and isolating the city of Leningrad. Artillery bombardments, which had begun in August 1941, increase in intensity during 1942 and will be stepped up further during 1943. German shelling's and bombings will kill 5,723 and wound 20,507 civilians in Leningrad during the length of the siege.

September 8, 1941: Keitel's OKW issues a regulation for the treatment of Soviet POW's. It states that Russian soldiers will fight by any methods for the idea of Bolshevism and that consequently they have lost any claim to treatment in accordance with the Geneva Convention. Stern measures are to be employed against them, including the free use of weapons. The politically undesirable prisoners are to be segregated from the others and turned over to 'special purpose units' of the Security Police and the Security Service. There is to be the closest cooperation between the military commanders and these police units.

From Keitel's IMT testimony: Perhaps I can say by way of introduction that these directives were not issued until September, which can be attributed to the fact that at first an order by Hitler existed, saying that Russian prisoners of war were not to be brought back to Reich territory. This order was later on rescinded. Now, regarding the directive of 8 September 1941, the full text of which I have before me, I should like to say that all these instructions have their origin in the idea that this was a battle of nationalities, for the initial phrase reads, "Bolshevism is the deadly enemy of National Socialist Germany." That, in my opinion, immediately shows the basis on which these instructions were made and the motives and ideas from which they sprang. It is a fact that Hitler, as I explained yesterday, did not consider this a battle between two states to be waged in accordance with the rules of international law but as a conflict between two ideologies. There are also several statements in the document regarding selection from two points of view: Selection of people who seem, if I may express it in this way, not dangerous to us; and the selection of those who, on account of their political activities and their fanaticism, had to be isolated as representing a particularly dangerous threat to National Socialism.

Turning to the introductory letter, I may say that it has already been presented here by the Prosecutor of the Soviet Union. It is a letter from the Chief of the Intelligence Service of the OKW, Admiral Canaris, reminding one of the general order which I have just mentioned and adding a series of remarks in which he formulates and emphasizes his doubts about the decree and his objections to it. About the memorandum which is attached I need not say any more. It is an extract, and also the orders which the Soviet Union issued in their turn I think on 1 July, for the treatment of prisoners of war, that is, the directives for the treatment of German prisoners of war. I received this on 15 September, whereas the other order had been issued about a week earlier; and after studying this report from Canaris, I must admit I shared his objections. Therefore I took all the papers to Hitler and asked him to cancel the provisions and to make a further statement on the subject. The Führer said that we could not expect that German prisoners of war would be treated according to the Geneva Convention or international law on the other side. We had no way of investigating it and he saw no reason to alter the directives he had issued on that account. He refused point-blank, so I returned the file with my marginal notes to Admiral Canaris. The order remained in force... ...

According to my own personal observations and the reports which have been put before me, the practice was, if I may say so, very much better and more favorable than the very severe instructions first issued when it had been agreed that the prisoners of war were to be transported to Germany. At any rate, I have seen numerous reports stating that labor conditions, particularly in agriculture, but also in war economy and in particular in the general institution of war economy such as railways, the building of roads, and so on, were considerably better than might have been expected, considering the severe terms of the instructions.

1. Since the beginning of the campaign against Soviet Russia, Communist insurrection movements have broken out everywhere in the area occupied by Germany. The type of action taken is growing from propaganda measures and attacks on individual members of the Armed Forces into open rebellion and widespread guerilla warfare. It can be seen that this is a mass movement centrally directed by Moscow, which is also responsible for the apparently trivial isolated incidents in areas which up to now have been otherwise quiet. In view of the many political and economic crises in the occupied areas, it must, moreover, be anticipated that nationalist and other circles will make full use of this opportunity of making difficulties for the German occupying forces by associating themselves with the Communist insurrection. This creates an increasing danger to the German war effort, which shows itself chiefly in general insecurity for the occupying troops, and has already led to the withdrawal of forces to the main centers of disturbance.

2. The measures taken up to now to deal with this general Communist insurrection movement have proved inadequate. The Führer has now given orders that we take action everywhere with the most drastic means, in order to crush the movement in the shortest possible time. Only this course, which has always been followed successfully throughout the history of the extension of influence of great peoples, can restore order.

3. Action taken in this matter should be in accordance with the following general directions: a. It should be inferred in every case of resistance to the German occupying forces, no matter what the individual circumstances, that it is of Communist origin. b. In order to nip these machinations in the bud the most drastic measures should be taken immediately and on the first indication, so that the authority of the occupying forces may be maintained and further spreading prevented. In this connection it should be remembered that a human life in the countries concerned frequently counts for nothing, and a deterrent effect can be attained only by unusual severity.

The death penalty for 50-100 Communists should generally be regarded in these cases as suitable atonement for one German soldier's death. The way in which sentence is carried out should still further increase the deterrent effect. The reverse course of action, that of imposing relatively lenient penalties and of being content, for purposes of deterrence, with the threat of more severe measures does not accord with these principles and shall not be followed...The commanding officers in the occupied territories shall see to it that these principles are made known without delay to all military establishments concerned in dealing with Communist measures of insurrection.

From Keitel's IMT testimony: Document UK-25, the Führer Order of the 16 September 1941, as has just been stated, is concerned with communist uprisings in occupied territories, and the fact that this is a Führer order has already been mentioned. I must clarify the fact that this order, so far as its contents are concerned, referred solely to the Eastern regions, particularly to the Balkan countries. I believe that I can prove this by the fact that there is attached to this document a distribution list, that is, a list of addresses beginning, "Wehrmacht Commander Southeast for Serbia, Southern Greece, and Crete." This was, of course, transmitted also to other Wehrmacht commanders and also to the OKH with the possibility of its being passed on to subordinate officers.

I believe that this document, which, for the sake of saving time, I need not read here, has several indications that the assumption on the part of the French Prosecution that this is the basis for the hostage law to be found in Document Number 1588-PS is false, and that there is no causal nexus between the two. It is true that the date of this hostage law is also September—the number is hard to read—but, as far as its contents are concerned, these two matters are, in my opinion, not connected. Moreover, the two military commanders in France and Belgium never received this order from the OKW, but they may have received it through the OKH, a matter which I cannot check because I do not know. Regarding this order of 16 September 1941, I should like to say that its great severity can be traced back to the personal influence of the Fuehrer. The fact that it is concerned with the Eastern region is already to be seen from the contents and from the introduction and does not need to be substantiated any further. It is correct that this order of 16 September 1941 is signed by me. ...

I pointed out that these instructions were addressed in the first place to the Commander-in-Chief of the Wehrmacht offices in the Southeast; that is, the Balkan regions, where extensive partisan warfare and a war between the leaders had assumed enormous proportions, and secondly, because the same phenomena had been observed and established on the same or similar scale in certain defined areas of the occupied Soviet territory. ...I signed the order and by doing so I assumed responsibility within the scope of my official jurisdiction. ...I knew from years of experience that in the Southeastern territories and in certain parts of the Soviet territory, human life was not respected to the same degree. ...I signed the order but the figures contained in it are alterations made personally by Hitler himself. ...The idea was that the only way of deterring them was to demand several sacrifices for the life of one soldier, as is stated here. ...Then I must say that with reference to the underlying principle there was a difference of opinion, the final results of which I no longer feel myself in a position to justify, since I added my signature on behalf of my department. There was a fundamental difference of opinion on the entire question.

I. All Frenchmen held in custody of whatever kind, by the German authorities or on behalf of German authorities in France, are to be considered as hostages as from 23 August. If any further incident occurs, a number of these hostages are to, be shot, to be determined according to the gravity of the attempt.'

2. On 19 September 1941 by an announcement to the Plenipotentiary of the French Government attached to the Military Commander in France, I ordered that, as from 19 September 1941, all French males who are under arrest of any kind by the French authorities or who are taken into custody because of Communist or anarchistic agitation are to be kept under arrest by the French authorities also on behalf of the Military Commander in France.

3. On the basis of my notification of the 22d of August 1941 and of my order of the 19th of September 1941 the following groups of persons are therefore hostages:

(a) All Frenchmen who are kept in detention of any kind whatsoever by the German authorities, such as police custody, imprisonment on remand, or penal detention.

(b) All Frenchmen who are kept in detention of any kind whatsoever by the French authority on behalf of the German, authorities. This group includes:

(aa) All Frenchmen who are kept in detention of any kind whatsoever by the French authorities because of Communist or anarchist activities.

(bb) All Frenchmen on whom the French penal authorities impose prison terms at the request of the German military courts and which the latter consider justified.

(cc) All Frenchmen who are arrested and kept in custody by the French authorities upon demand of the German authorities or who are being handed over by the Germans to French authorities with the order to keep them under arrest.

(c) Stateless inhabitants who have already been living for some time in France are to be considered as Frenchmen within the meaning of my notification of the 22d of August 1941'.

III. Release from detention. Persons who were not yet in custody on 22 August 1941 or on 19 September 1941 but who were arrested later or are still being arrested are hostages as from the date of detention if the other conditions apply to them. The release of arrested persons authorized on account of expiration of sentences, lifting of the order for arrest, or for other reasons will not be affected by my announcement of 22 August 1941. Those released are no longer hostages. In as far as persons are in custody of any kind with the French authorities for Communist or anarchist activity, their release is possible only with my approval as I have informed the French Government....

VI. Lists of hostages. If an incident occurs which according to my announcement of 22 August 1941 necessitates the shooting of hostages, the execution must immediately follow the order. The district commanders, therefore, must select for their own districts from the total number of prisoners (hostages es) those who, from a practical point of view, may be considered for execution and enter them on a list of hostages. These lists of hostages serve as a basis for the proposals to be submitted to me in the case of an execution.

I. According to the observations made so far, the perpetrators of outrages originate from Communist or anarchist terror gangs. The district commanders are, therefore, to select from those in detention (hostages), those persons who, because of their Communist or anarchist views in the past or their positions in such organizations or their former attitude in other ways, are most suitable for execution.

In making the selection it should be borne in mind that the better known the hostages to be shot, the greater will be the deterrent effect on the perpetrators, themselves, and on those persons who, in France or abroad, bear the moral responsibility—as instigators or by their propaganda—for acts of terror and sabotage. Experience shows that the instigators and the political circles interested in these plots are not concerned about the life of obscure followers, but are more likely to be concerned about the lives of their own former officials. Consequently, we must place at the head of these lists:

(a) Former deputies and officials of Communist or anarchist organizations.

(b) Persons (intellectuals) who have supported the spreading of Communist ideas by word of mouth or writing.

(c) Persons who have proved by their attitude that they are particularly dangerous.

(d) Persons who have collaborated in the distribution of leaflets...

2. Following the same directives, a list of hostages is to be prepared from the prisoners with De Gaullist sympathies.

3. Racial Germans of French nationality who are imprisoned for Communist or anarchist activity may be included in the list. Special attention must be drawn to their German origin on the attached form. Persons who have been condemned to death but who have been pardoned may also be included in the lists.... ...

5. The lists have to record for each district about 150 persons and for the Greater Paris Command about 300 to 400 people. The district chiefs should always record on their lists those persons who had their last residence or permanent domicile in their districts, because the persons to be executed should, as far as possible, be taken from the district where the act was committed.... "The lists are to be kept up to date. Particular attention is to be paid to new arrests and releases.' ...

VII. Proposals for executions: In case of an incident which necessitates the shooting of hostages, within the meaning of my announcement of 22 August 1941, the district chief in whose territory the incident happened is to select from the list of hostages persons whose execution he wishes to propose to me. In making the selection he must, from the personal as well as local point of view, draw from persons belonging to a circle which presumably includes the guilty...

For execution, only those persons who were already under arrest at the time of the crime may be proposed. The proposal must contain the names and number of the persons proposed for execution, that is, in the order in which the choice is recommended...When the bodies are buried, the burial of a large number in a common grave in the same cemetery is to be avoided, in order not to create places of pilgrimage which, now or later, might form centers for anti-German propaganda. Therefore, if necessary, burials must be carried out in various places.

From Keitel's IMT testimony: It is possible, and I do recall one such case, Stulpnagel called me up from Paris on such a matter because he had received an order from the Army to shoot a certain number of hostages for an attack on members of the German Wehrmacht. He wanted to have this order certified by me. That happened and I believe it is confirmed by a telegram, which has been shown to me here. It is also confirmed that at that time I had a meeting with Stulpnagel in Berlin. Otherwise, the relations between myself and these two military commanders were limited to quite exceptional matters, in which they believed that with my help they might obtain certain support with regard to things that were very unpleasant for them, for example, in such questions as labor allocation, that is, workers from Belgium or France destined for Germany, where also, in one case, conflicts arose between the military commanders and their police authorities. In these cases I was called up directly in order to mediate.

October 1, 1941: From an order signed by Keitel:From Keitel's IMT testimony: I was not at all particular and the idea did not originate with me; but it is in accordance with the instructions, the official regulations, regarding hostages which I discussed yesterday or on the day before and which state that those held as hostages must come from the circles responsible for the attacks. That is the explanation, or confirmation, of that as far as my memory goes. ...I have already explained how orders for shooting hostages, which were also given, were to be applied and how they were to be carried out in the case of those deserving of death and who had already been sentenced. ...it says only that hostages must be taken; but it says nothing about shooting them. ...I personally had different views on the hostage system, but I signed it, because I had been ordered to do so.

October 3, 1941: Hitler opens up the charitable Winter Aid campaign with a speech at the Sportpalast:October 7, 1941: From a top secret order of the Supreme Command of the Armed Forces signed by Jodl:

From Keitel's IMT testimony: I think it was my last or the next to the last visit to Von Leeb where the questions of capitulation, that is to say, the question of the population of Leningrad, played an important role, which worried him very much at that time because there were certain indications that the population was streaming out of the city and infiltrating into his area. I remember that at that time he asked me to make the suggestion to the Führer that, as he could not take over and feed 1 million civilians within the area of his army group, a sluice, so to speak, should be made towards the east, that is, the Russian zone, so that the population could flow out in that direction. I reported that to the Führer at that time. ...According to Von Leeb a certain pressure exerted by the population to get through the German lines made itself felt at the time.

October 25, 1941: US Department of State Bulletin:October 29, 1941: From Appendix 1 to Operational Order Number 14 of the Chief of the Security Police and SD:

November 7, 1941: Göring, at a conference at the Air Ministry:

For employment in the interior and the Protectorate the following are to have priority:

(a) At the top, the coal mining industry. Order by the Fuehrer to investigate all mines as to suitability for employment of Russians, in some instances manning the entire plant with Russian laborers.

(b) Transportation (construction of locomotives and cars, repair shops, etc.). Railroad-repair and factory workers are to be sought out from the prisoners of war. Rail is the most important means of transportation in the East.

(c) Armament industries. Preferably factories of armor and guns. Possibly also construction of parts for aircraft engines. Suitable complete sections of factories to be manned exclusively by Russians if possible.

For the remainder, employment in groups. Use in factories of tool machinery, production of farm tractors, generators, etc. In emergency, erect in some places barracks for casual workers who are used in unloading units and for similar purposes. (Reich Minister of the Interior through communal authorities.) OKW/AWA is competent for procuring Russian prisoners of war.

Employment through Planning Board for employment of all prisoners of war. If necessary, offices of Reich commissariats. No employment where danger to men or supply exists, that is, factories exposed to explosives, waterworks, power-works, etc. No contact with German population, especially no 'solidarity.' German worker as a rule is foreman of Russians. Food is a matter of the Four Year Plan. Procurement of special food (cats, horses, etc. Clothes, billeting, messing somewhat better than at home where part of the people live in caves. Supply of shoes for Russians; as a rule wooden shoes, if necessary install Russian shoe repair shops. Examination of physical fitness in order to avoid importation of diseases. Clearing of mines as a rule by Russians; if possible by selected Russian engineer troops.

November 9, 1941: From a memorandum entitled 'Transportation of Russian Prisoners of War, destined for Execution, into the Concentration Camps’:

In order to prevent, if possible, similar occurrences in the future, I therefore order that, effective from today on, Soviet Russians declared definitely suspect and obviously marked by death (for example with hunger-typhus) and therefore not able to withstand the exertions of even a short march on foot shall in the future, as a matter of basic principle, be excluded from the transport into the concentration camps for execution.

From Keitel's IMT testimony: The OKW was responsible in the case of incidents which violated general orders, that is, basic instructions issued by the OKW, or in the case of failure to exercise the right to inspect (POW camps). In such circumstances I would say that the OKW was responsible. ...At first, in the early days of the war, (the OKW exercised its right to inspect camps) through an inspector of the Prisoners of War Organization (the KGW), who was at the same time the office or departmental chief of the department KGW in the General Office of the Armed Forces. In a certain sense, he exercised a double function. Later on, after 1942 I believe, it was done by appointing an inspector general who had nothing to do with the correspondence or official work on the ministerial side. ...

If a protecting power wished to send a delegation to inspect camps, that was arranged by the department or the inspector for the prisoner-of-war matters, and he accompanied the delegation. Perhaps I ought to say that, as far as the French were concerned, Ambassador Scapini carried out that function personally and that a protecting power did not exist in this form. ...I do not know whether the procedure adopted in camps was always in accordance with the basic instructions, which were to render possible a direct exchange of views between prisoners of war and visitors from their own countries. As a general rule, it was allowed and made possible. ...

I did concern myself with the general instructions. Apart from that, my being tied to the Fuehrer and to headquarters naturally made it impossible for me to be in continuous contact with my offices. There were, however, the KGW branch office and the inspector, as well as the Chief of the General Armed Forces Office who was, in any case, responsible to me and dealt with these matters. These three departments had to deal with the routine work; and I, myself, was called on when decisions had to be made and when the Führer interfered in person, as he frequently did, and gave orders of his own. ...It is true that in this connection there was a difference in treatment due to the view, frequently stated by the Führer, that the Soviet Union on their part had not observed or ratified the Geneva Convention. It was also due to the part played by "ideological conceptions regarding the conduct of the war." The Fuehrer emphasized that we had a free hand in this field.

From Keitel's IMT testimony: May I say, first of all, that there was constant friction between Himmler and the corresponding police services and the departments of the Wehrmacht which worked in this sphere and that this friction never stopped. It was apparent right from the first that Himmler at least desired to have the lead in his own hands, and he never ceased trying to obtain influence of one kind or another over prisoner-of-war affairs. The natural circumstances of escapes, recapture by police, searches and inquiries, the complaints about insufficient guarding of prisoners, the insufficient security measures in the camps, the lack of guards and their inefficiency—all these things suited him; and he exploited them in talks with Hitler, when he continually accused the Wehrmacht behind its back, if I may use the expression, of every possible shortcoming and failure to carry out their duty. As a result of this Hitler was continually intervening, and in most cases I did not know the reason. He took up the charges and intervened constantly in affairs so that the Wehrmacht departments were kept in what I might term a state of perpetual unrest. In this connection, since I could not investigate matters myself, I was forced to give instructions to my departments in the OKW. ...

He (Himmler) wanted not only to gain influence but also, as far as possible, to have prisoner-of-war affairs under himself as Chief of Police in Germany so that he would reign supreme in these matters, if I may say so. ...

The searches and inquiries, made at certain intervals in Germany for escaped persons, made it clear that the majority of these prisoners of war did not go back to the camps from which they had escaped so that obviously they had been retained by police departments and probably used for labor under the jurisdiction of Himmler. Naturally, the number of escapes increased every year and became more and more extensive. For that, of course, there are quite plausible reasons. ...

The departments which dealt with this were the State Labor Offices in the so-called Reich Labor Allocation Service, which had originally been in the hands of the Labor Minister and was later on transferred to the Plenipotentiary for the Allocation of Labor. In practice it worked like this. The State Labor Offices applied for workers to the Army district commands which had jurisdiction over the camps. These workers were supplied as far as was possible under the existing general directives. ...

In general, of course, they had to supervise it, so that allocation was regulated according to the general basic orders. It was not possible, of course, and the inspector was not in a position to check on how each individual was employed; after all, the army district commanders and their generals for the KGW were responsible for that and were the appropriate persons. The actual fight, as I might call it, for prisoner-of-war labor did not really start until 1942. Until then, such workers had been employed mainly in agriculture and the German railway system and a number of general institutions, but not in industry. This applies especially to Soviet prisoners of war who were, in the main, agricultural workers.

(The Japanese Ambassador continues his dispatch:) Concerning this point, in view of the fact that Ribbentrop has said in the past that the United States would undoubtedly try to avoid meeting German troops, and from the tone of Hitler's recent speech as well as that of Ribbentrop's, I feel that the German attitude toward the United States is being considerably stiffened. There are indications at present that Germany would not refuse to fight the United States if necessary...

In any event Germany has absolutely no intention of entering into any peace with England. We are determined to remove all British influence from Europe. Therefore, at the end of this war, England will have no influence whatsoever in international affairs. The island empire of Britain may remain, but all of her other possessions throughout the world will probably be divided three ways by Germany, the United States and Japan. In Africa, Germany will be satisfied with, roughly, those parts which were formerly German colonies. Italy will be given the greater share of the African colonies. Germany desires, above all else, to control European Russia.

(Quoting) Japanese Ambassador: "I am fully aware of the fact that Germany's war campaign is progressing according to schedule smoothly. However, suppose that Germany is faced with the situation of having not only Great Britain as an actual enemy but also all of those areas in which Britain has influence, and those countries which have been aiding Britain as actual enemies, as well. Under such circumstances, the war area will undergo considerable expansion, of course. What is your opinion of the outcome of the war under such an eventuality. Ribbentrop: We would like to end this war during next year. However, under certain circumstances it is possible that it will have to be continued into the following year. Should Japan become engaged in a war against the United States, Germany, of course, would join the war immediately. There is absolutely no possibility of Germany's entering into a separate peace with the United States under such circumstances. The Führer is determined on that point."

From Keitel's IMT testimony: In the course of all this time, until the Japanese entry into the war against America, there were two points of view that were the general directives or principles which Hitler emphasized to us. One was to prevent America from entering the war under any circumstances; consequently to renounce military operations in the seas, as far as the Navy was concerned. The other, the thought that guided us soldiers, was the hope that Japan would enter the war against Russia; and I recall that around November and the beginning of December 1941, when the advance of the German armies west of Moscow was halted and I visited the front with Hitler, I was asked several times by the generals, "When is Japan going to enter the war?"

The reasons for their asking this were that again and again Russian Far East divisions were being thrown into the fight via Moscow, that is to say, fresh troops coming from the Far East. That was about 18 to 20 divisions, but I could not say for certain. I was present in Berlin during Matsuoka's visit, and I saw him also at a social gathering, but I did not have any conversation with him. All the deductions that might be made from Directive 24, C-75, and which I have learned about from the preliminary examination during my interrogation, are without any foundation for us soldiers, and there is no justification for anyone's believing that we were guided by thoughts of bringing about a war between Japan and America, or of undertaking anything to that end. In conclusion, I can say only that this order was necessary because the branches of the Wehrmacht offered resistance to giving Japan certain things, military secrets in armament production, unless she were in the war.

From Keitel's IMT testimony: During the winter of 1941-42 the problem of replacing soldiers who had dropped out arose, particularly in the eastern theater of war. Considerable numbers of soldiers fit for active service were needed for the front and the armed services. I remember the figures. The army alone needed replacements numbering from 2 to 2.5 million men every year. Assuming that about 1 million of these would come from normal recruiting and about half a million from rehabilitated men, that is, from sick and wounded men who had recovered, that still left 1.5 million to be replaced every year. These could be withdrawn from the war economy and placed at the disposal of the services, the Armed Forces. From this fact resulted the close correlation between the drawing off of these men from the war economy and their replacement by new workers. This manpower had to be taken from the prisoners of war on the one hand and Plenipotentiary Sauckel, whose functions may be summarized as the task of procuring labor, on the other hand. This connection kept bringing me into these matters, too, since I was responsible for the replacements for all the Wehrmacht—Army, Navy, and Air Force—in other words, for the recruiting system. That is why I was present at discussions between Sauckel and the Führer regarding replacements and how these replacements were to be found. ...

Up to 1942 or thereabouts we had not used prisoners of war in any industry even indirectly connected with armaments. This was due to an express prohibition issued by Hitler, which was made by him because he feared attempts at sabotaging machines, production equipment, et cetera. He regarded things of that kind as probable and dangerous. Not until necessity compelled us to use every worker in some capacity in the home factories did we abandon this principle. It was no longer discussed; and naturally prisoners of war came to be used after that in the general war production, while my view which I, that is the OKW, expressed in my general orders, was that their use in armament factories was forbidden; I thought that it was not permissible to employ prisoners of war in factories which were exclusively making armaments, by which I mean war equipment, weapons, and munitions. For the sake of completeness, perhaps I should add that an order issued by the Führer at a later date decreed further relaxation of the limitations of the existing orders. I think the Prosecution stated that Minister Speer is supposed to have spoken of so many thousands of prisoners of war employed in the war economy.

I may say, however, that many jobs had to be done in the armament industry which had nothing to do with the actual production of arms and ammunition. ...there are documents to show that prisoners of war in whose case the disciplinary powers of the commander were not sufficient were singled out and handed over to the Secret State Police. Finally, I have already mentioned the subject of prisoners who escaped and were recaptured, a considerable number of whom, if not the majority, did not return to their camps. Instructions on the part of the OKW or the Chief of Prisoners of War Organization ordering the surrender of these prisoners to concentration camps are not known to me and have never been issued. But the fact that, when they were handed over to the police, they frequently did end up in the concentration camps has been made known here in various ways, by documents and witnesses. That is my explanation.

December 7, 1941 Nacht und Nebel (Night and Fog) Decree:

I. Within the occupied territories, the adequate punishment for offences committed against the German State or the occupying power which endanger their security or a state of readiness is on principle the death penalty.

II. The offences listed in paragraph I as a rule are to be dealt with in the occupied countries only if it is probable that sentence of death will be passed upon the offender, at least the principal offender, and if the trial and the execution can be completed in a very short time. Otherwise the offenders, at least the principal offenders, are to be taken to Germany.

III. Prisoners taken to Germany are subjected to military procedure only if particular military interests require this. In case German or foreign authorities inquire about such prisoners, they are to be told that they were arrested, but that the proceedings do not allow any further information.

IV. The Commanders in the occupied territories and the Court authorities within the framework of their jurisdiction, are personally responsible for the observance of this decree.

V. The Chief of the High Command of the Armed Forces determines in which occupied territories this decree is to be applied. He is authorized to explain and to issue executive orders and supplements. The Reich Minister of Justice will issue executive orders within his own jurisdiction.

From Keitel's IMT testimony: I must state that it is perfectly clear to me that the connection of my name with this so-called Nacht und Nebel order is a serious charge against me, even though it can be seen from the documents that it is a Führer order. Consequently I should like to state how this order came about.

Since the beginning of the Eastern campaign and in the late autumn of 1941 until the spring of 1942, the resistance movements, sabotage and everything connected with it increased enormously in all the occupied territories. From the military angle it meant that the security troops were tied down, having to be kept on the spot by the unrest. That is how I saw it from the military point of view at that time. And day by day, through the daily reports we could picture the sequence of events in the individual occupation sectors. It was impossible to handle this summarily; rather, Hitler demanded that he be informed of each individual occurrence, and he was very displeased if such matters were concealed from him in the reports by military authorities. He got to know about them all the same.

In this connection, he said to me that it was very displeasing to him and very unfavorable to establishing peace that, owing to this, death sentences by court-martial against saboteurs and their accomplices were increasing; that he did not wish this to occur, since from his point of view it made appeasement and relations with the population only more difficult. He said at that time that a state of peace could be achieved only if this were reduced and if, instead of death sentences—to shorten it—in case a death sentence could not be expected and carried out in the shortest time possible, as stated here in the decree, the suspect or guilty persons concerned—if one may use the word 'guilty'—should be deported to Germany without the knowledge of their families and be interned or imprisoned instead of lengthy court-martial proceedings with many witnesses. I expressed the greatest misgivings in this matter and know very well that I said at that time that I feared results exactly opposite to those apparently hoped for. I then had serious discussions with the legal adviser of the Wehrmacht, who, had similar scruples, because there was an elimination of ordinary legal procedures. I tried again to prevent this order from being issued or to have it modified.

My efforts were in vain. The threat was made to me that the Minister of Justice would be commissioned to issue a corresponding decree, should the Wehrmacht not be able to do so. Now may I refer to details only insofar as these ways were provided in this order, L-90, of preventing arbitrary application, and these were primarily as follows: The general principles of the order provided expressly that such deportation or abduction into Reich territory should take place only after regular court-martial proceedings, and that in every case the officer in charge of jurisdiction, that is, the divisional commander must deal with the matter together with his legal adviser, in the legal way, on the basis of preliminary proceedings. I must say that I believed then that every arbitrary and excessive application of these principles was avoided by this provision. You will perhaps agree with me that the words in the order, "It is the will of the Fuehrer after long consideration..." put in for that purpose, were not said without reason and not without the hope that the addressed military commander would also recognize from this that this was a method of which we did not approve and did not consider to be right.

Finally we introduced a reviewing procedure into the order so that through the higher channels of appeal, that is, the Military Commander in France and the Supreme Command or Commander of the Army, it would be possible to try the case legally by appeal proceedings if the verdict seemed open to question, at least, within the meaning of the decree. I learned here for the first time of the full and monstrous tragedy, namely, that this order, which was intended only for the Wehrmacht and for the sole purpose of determining whether an offender who faced a sentence in jail could be made to disappear by means of this Nacht und Nebel procedure, was obviously applied universally by the police, as testified by witnesses whom I have heard here, and according to the Indictment which I also heard, and so the horrible fact of the existence of whole camps full of people deported through the Nacht und Nebel procedure has been proved. In my opinion, the Wehrmacht, at least I and the military commanders of the occupied territories who were connected with this order, did not know of this.

At any rate it was never reported to me. Therefore this order, which in itself was undoubtedly very dangerous and disregarded certain requirements of law such as we understood it, was able to develop into that formidable affair of which the Prosecution have spoken. The intention was to take those who were to be deported from their home country to Germany, because Hitler was of the opinion that penal servitude in wartime would not be considered by the persons concerned as dishonorable in cases where it was a question of actions by so-called patriots. It would be regarded as a short detention which would end when the war was over. These reflections have already been made in part in the note. If you have any further questions, please put them. ...

The order that was given at that time was that these people should be turned over to the German authorities of justice. This letter signed "by order" and then the signature, was issued 8 weeks later than the decree itself by the Amt Ausland/Abwehr im Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (Foreign Affairs/Defense Office of the Armed Forces High Command) as I can see from my official correspondence. It indicates the conferences, that is, the agreements, which had to be reached at that time, regarding the method by which these people were to be taken from their native countries to Germany. They were apparently conducted by this Amt Abwehr, which evidently ordered police detachments as escorts. That can be seen from it. I might mention in this connection—I must have seen it—that it did not seem objectionable at that time, because I could have, and I had, no reason to assume that these people were being turned over to the Gestapo, frankly speaking, to be liquidated, but that the Gestapo was simply being used as the medium in charge of the transportation to Germany. I should like to emphasize that particularly, so that there can be no doubt that it was not our idea to do away with the people as was later done in that Nacht und Nebel camp.

[For much detail see, Click here.]

December 11, 1941: Hitler declares war on the United States before the Reichstag:

From Inside the Third Reich by Albert Speer: In keeping with his character, Hitler gladly sought advice from persons who saw the situation even more optimistically and elusively than he himself. Keitel was often one of those. When the majority of the officers would greet Hitler's decisions with marked silence, Keitel would frequently feel called upon to speak up in favor of the measure. Constantly in Hitler's presence, he had completely succumbed to his influence. From an honorable, solidly respectable general he had developed in the course of years into a servile flatterer with all the wrong instincts. Keitel hated his own weakness; but the hopelessness of any dispute with Hitler had ultimately brought him to the point of not even trying to form his own opinion. If, however, he had offered resistance and stubbornly insisted on a view of his own, he would merely have been replaced by another Keitel.

December 12, 1941: Keitel defends the Night and Fog Decree:January 3, 1942: From a Hitler Order:

February 8, 1942: While departing by plane from a meeting with Hitler at the Wolf's Lair (Wolfsschanze) at Rastenburg, builder of the Autobahn Dr. Fritz Todt, director of the Organization Todt and Reichsminister of Armaments, dies as his Junker 52 aircraft mysteriously explodes. He will be buried in the Invalidenfriedhof (The Invalids' Cemetery), located in the Scharnhorst-Strasse in Berlin and become the first holder (posthumously) of the Deutscher Orden (German Order). Note: It has been suggested that Todt was the victim of an assassination plot, but no evidence has ever been found to corroborate the intriguing notion.

From Keitel's US SBS interview:

Q: What was the reason for the considerable increase in production? Was the increase due to the urgent need or due to the skill of Minister Speer?

Keitel: All included, Speer's secret was the drawing of factories of similar production together. By employing them all on the same work he demanded higher accomplishments.

Q: Who formulated the program?

Keitel: Speer. The requirements came directly from the Führer after conference between the OKW and myself, and in the case of tanks, the Inspector General of Armored Forces. I have seen a case where industry said in the case of flak guns that they could produce 200 and the Führer demanded 500. Then the industry would say that they probably might produce 350, whereupon the Führer would call the leading industrialists and have a conference with them. He told them to think the matter over; and the next day they would tell him that they would try to produce those 500.

Q: Would you say, in general, that the requirements of the Wehrmacht were met?

Keitel: In general, the requirements were nearly always met and in some cases exceeded. An all inclusive program would be formulated and presented to the Führer. He would look at the figures and then start correcting them. He always wanted more and we (the people from OKW) could never refuse having more, but as a result of that the plant management would then request the release of additional men from the Armed Forces in order to meet the increased program, and then the Führer would usually decide that these men had to be released to that factory under all circumstances. But Speer's biggest difficulties were the frequent changes in the requirements and the necessary change-over that had to follow. I do believe that the continuous changes have caused the Speer Ministry tremendous difficulties.

The Supreme Commanders often came to Hitler and complained of not having enough of some items. Hitler would immediately telephone to Speer and the conversation would develop something like this. 'Speer, how many searchlights are you producing? '1,000,' was the reply. 'All right, we will make it 5,000' and Speer would reply that he could not do it. Whereupon Hitler would say 'Think it over until tomorrow, I want 5,000 and that is my order.' So Speer would start and try all possibilities and even though he probably was not able to produce 5,000, the next month would at least yield 2,000; and when he came to the Führer he was told: 'You must demand the impossible in order to get the maximum.'

Q: Was the Wehrmacht satisfied with the work of Speer in general?

Keitel: We had a very good and loyal work relationship with Speer. He decided upon a lot of things himself, without Hitler, as for instance when more spades were needed. I, personally, had very heavy fights with him with regard to manpower, and at the same time, I had to worry about Speer having all the people he needed for his production.

Q: Do you think that Speer's demands for labor were reasonable?

Keitel: I had at least to try to press him down, and we also succeeded in the last two years in again extricating a considerable number of young soldiers out of the armament industry, due in large part to the rationalization of production in different factories. [Note: The US SBS will conclude that Speer’s efforts prolonged the war by as many as two years. -W]

From Keitel's US SBS interview: Q: Would the production have been higher without Hitler's interference?

Keitel: No, it was due to his personal influence that I ordered General Buhle to deal with the development of these problems. When then, the Supreme Commander of the East came to report, Hitler would ask him at the end; 'What are you short of?' He would complain that ammunition or guns were lacking. As a result of these conferences Hitler would sit down at the end of the day and look through his lists. In those lists Speer had to note in every month the monthly production for all kinds of armaments, ammunition and equipment in both the required and actually produced numbers. Here the Fuehrer had a picture of how for instance, the production of machine guns developed. If somebody came in and demanded those things, he would be immediately able to check them and said: 'Here I must demand something immediately.' The same evening he would call me or General Buhle, who knew a lot about these things and became Hitler's right hand in these matters. Then he would talk to Speer the next morning and give him the orders... ...

The last day of each month at 6 o'clock in the afternoon, you could not stop the Führer from telephoning Speer and asking him about the number of the current month's production. The next morning, he would call the Chiefs of Staff of the Armed Forces and tell them what the monthly production was, so that they could figure that in their plans. But when told that next month's production would not be available operationally for quite a period of time, he would say: 'But regardless, gentlemen, this is what you shall have."

February 24, 1942: Hitler speaks to the Reich via radio:

March 1, 1942: From a signed Hitler Order:

March 21, 1942: Sauckel is appointed Generalbevollmächtigter für den Arbeitseinsatz (General Plenipotentiary for the Allocation of Labor).

From Keitel's IMT testimony: As far as I know, workers came from occupied territories, especially those in the West: Belgium, Holland—I do not know about Holland, but certainly France—to Germany. According to what I heard, I understood at the time that it was done by recruiting volunteers. I think I remember that General von Stulpnagel, the military commander of Paris, told me in Berlin once during a meeting that more than 200,000 had volunteered, but I cannot remember exactly when that was. ...the OKW had nothing to do with it. These questions were handled through the usual channels, the OKH, the Military Commanders in France and in Belgium and Northern France with the competent central authorities of the Reich at home, the OKW never had anything to do with it. ...

In occupied territories with civilian administration, the Wehrmacht was excluded from any executive powers in the administration, so that in these territories the Wehrmacht and its services had certainly nothing to do with it. Only in those territories which were still operational areas for the Army were executive powers given to military troops, high commanders, army commanders, et cetera. The OKW did not come into the official procedure here either. ...

The view held by Plenipotentiary Sauckel can obviously be explained by the fact that he knew neither the official service channels nor the functions of the Wehrmacht, that he saw me at one or two discussions on the furnishing of manpower, and, thirdly, that he sometimes came to see me when he had made his report and received his orders alone. He had probably been given orders to do so, in Hitler's usual way: Go and see the Chief of the OKW; he will do the rest. The OKW had no occasion to do anything. The OKW had no right to give orders, but in Sauckel's case I did take over the job of informing the OKH or the technical departments in the General Quartermaster's office. I have never issued orders or instructions of my own to the military commanders or other services in occupied territories. It was not one of the functions of the OKW.

April 17-19, 1942: After learning German and memorizing a map of the surrounding area, General Giraud lowers himself down the cliff of the mountain fortress where he is imprisoned. With shaved moustache, he eventually makes his way back to Vichy France.

From Lahousen's IMT testimony: The name 'Gustav' was applied not to an operation but to an undertaking similar to the one which was demanded for the elimination of Marshal Weygand. ...'Gustav' was the expression used by the Chief of the OKW (Keitel) as a cover name to be used in conversations on the question of General Giraud. ...The Chief of the OKW, Keitel, gave an order of this kind to Canaris, not in writing but an oral order. ...I knew of this order in the same way as certain other chiefs of the sections, that is Bentivegni, Chief of Abwehr Section I, Pieckenbrock and a few other officers. We all heard it at a discussion with Canaris. ...The essential part of this order was to eliminate Giraud, in a fashion similar to Weygand. ...I mean the same as in the case of Marshal Weygand, that is, it was intended and ordered that he was to be killed. ...

This order was given to Canaris several times. I cannot say for certain when it was given for the first time as I was not present in person. It was probably after the flight of Giraud from Konigstein and prior to the attempt on the life of Heydrich, in Prague. According to my notes, this subject was discussed with me by Keitel in July of the same year, in the presence of Canaris. ...I cannot repeat his (Keitel's) exact words, but the meaning was that he proclaimed the intention of having Giraud killed, and asked me, as in the case of Weygand, how the matter was progressing or had progressed so far. ..I cannot remember the exact words (I used). I probably gave some evasive answer, or one that would permit gaining time. ...

According to my recollection, this question was once more discussed in August. The exact date can be found in my notes. Canaris telephoned me in my private apartment one evening and said impatiently that Keitel was urging him again about Giraud, and the section chiefs were to meet the next day on this question. The next day the conference was held and Canaris repeated in this larger circle what he had said to me over the phone the night before. That is, he was being continually pressed by Keitel that something must at last be done in this matter. Our attitude was the same as in the matter of Weygand. All those present rejected flatly this new demand to initiate and to carry out a murder. We mentioned our decision to Canaris, who also was of the same opinion and Canaris thereupon went down to Keitel in order to induce him to leave the Military Abwehr out of all such matters and requested that, as agreed prior to this, such matters should be left entirely to the SD.

In the meantime, while we were all there, I remember Pieckenbrock spoke, and I remember every word he said. He said it was about time that Keitel was told clearly that he should tell his Herr Hitler that we, the Military Abwehr, were no murder organization like the SD or the SS. After a short time, Canaris came back and said it was now quite clear that he had convinced Keitel that we, the Military Abwehr, were to be left out of such matters and further measures were to be left to the SD. I must observe here and recall that Canaris had said to me, once this order had been given, that the execution must be prevented at any cost. He would take care of that and I was to support him. ...

A little later, it must have been September, the exact date has been recorded, Keitel, then chief of the OKW, rang me up in my private apartment. He asked me, "What about 'Gustav'? You know what I mean by 'Gustav'?" I said, "Yes, I know." "How is the matter progressing? I must know, it is very urgent." I answered, "I have no information on the subject. Canaris has reserved this matter for himself, and Canaris is not here, he is in Paris." Then came the order from Keitel, or rather, before he gave the order, he put one more question: "You know that the others are to carry out the order?" By "the others," he meant the SS and SD. I answered, "Yes, I know." Then came an order from Keitel to immediately inquire of Mueller how the whole matter was progressing. "I must know it immediately," he said. I said, "Yes," but went at once to the office of the Ausland Abwehr, General Oster, and informed him what had happened, and asked for his advice as to what was to be done in this matter which was so extremely critical and difficult for Canaris and me. I told him—Oster already knew as it was—that Canaris so far had not breathed a word to the SD concerning what it was to do, that is, murder Giraud.

General Oster advised me to fly to Paris immediately and to inform Canaris and to warn him. I flew the next day to Paris and met Canaris at a hotel at dinner in a small circle, which included Admiral (Leopold) Bürckner, and I told Canaris what had happened. Canaris was horrified and amazed, and for a moment he saw no way out. During the dinner Canaris asked me in the presence of Bürckner and two other officers, that is, Colonel Rudolph, and another officer whose name I have forgotten, as to the date when Giraud had fled from Konigstein and when the Abwehr III conference had been held in Prague and at what time the assassination of Heydrich had taken place. I gave these dates, which I did not know by memory, to Canaris. When he had the three dates, he was visibly relieved, and his saddened countenance took on new life. He was certainly relieved in every way.

I must add that—at this important conference of the Abwehr III Heydrich was present. It was a meeting between Abwehr III and SD officials who were collaborating with it-officials who were also in the counterintelligence. Canaris then based his whole plan on these three dates. His plan was to attempt to show that at this conference he had passed on the order to Heydrich, to carry out the action. That is to say, his plan was to exploit Heydrich's death to wreck the whole affair. The next day we flew to Berlin, and Canaris reported to Keitel that the matter was taking its course, and that Canaris had given Heydrich the necessary instructions at the Abwehr III conference in Prague, and that Heydrich had prepared everything, that is, a special purpose action had been started in order to have Giraud murdered, and with that the matter was settled and brought to ruin. ...Nothing more happened. Giraud fled to North Africa, and much later only I heard that Hitler was very indignant about this escape, and said that the SD had failed miserably- so it is said to be written in shorthand notes in the records of the Hauptquartier (Headquarters) of the Führer. The man who told me this is in the American zone.

From Keitel's IMT testimony: Giraud's successful escape from the Fortress of Konigstein near Dresden on 19 April 1942 created a sensation; and I was severely reprimanded about the guard of this general's camp, a military fortress. The escape was successful despite all attempts to recapture the general, by police or military action, on his way back to France. Canaris had instructions from me to keep a particularly sharp watch on all the places at which he might cross the frontier into France or, Alsace-Lorraine, so that we could recapture him. The police were also put on to this job; 8 or 10 days after his escape it was made known that the general had arrived safely back in France. If I issued any orders during this search I probably used the words I gave in the preliminary interrogations, namely, "We must get the general back, dead or alive." I possibly did say something like that. He had escaped and was in France.

Second phase: Efforts, made through the Embassy by Abetz and Foreign Minister Ribbentrop to induce the general to return to captivity of his own accord, appeared not to be unsuccessful or impossible, as the general had declared himself willing to go to the occupied zone to discuss the matter. I was of the opinion that the general might possibly do it on account of the concessions hitherto made to Marshal Petain regarding personal wishes in connection with the release of French generals from captivity. The meeting with General Giraud took place in occupied territory, at the staff quarters of a German Army Corps, where the question of his return was discussed. The Military Commander informed me by telephone of the general's presence in occupied territory, in the hotel where the German officers were billeted. The commanding general suggested that if the general would not return voluntarily it would be a very simple matter to apprehend him if he were authorized to do so. I at once refused this categorically for I considered it a breach of faith. The general had come trusting to receive proper treatment and be returned unmolested.

Third phase: The attempt or desire to get the general back somehow into military custody arose from the fact that Canaris told me that the general's family was residing in territory occupied by German troops; and it was almost certain that the general would try to see his family, even if only after a certain period of time and when the incident had been allowed to drop. He suggested to me to make preparations for the recapture of the general if he made a visit of this kind in occupied territory. Canaris said that he himself would initiate these preparations through his Counterintelligence office in Paris and through his other offices. Nothing happened for some time; and it was surely quite natural for me to ask on several occasions, no matter who was with Canaris or if Lahousen was with him, "What has become of the Giraud affair?" or, in the same way, "How is the Giraud case getting on?" The words used by Mr. Lahousen were, "It is very difficult; but we shall do everything we can." That was his answer. Canaris made no reply. That strikes me as significant only now; but at the time it did not occur to me. ...

Fourth phase. This began with Hitler's saying to me: "This is all nonsense. We are not getting results. Counterintelligence is not capable of this and cannot handle this matter. I will turn it over to Himmler and Counterintelligence had better keep out of this, for they will never get hold of the general again." Admiral Canaris said at the time that he was counting on having the necessary security measures taken by the French secret state police in case General Giraud went to the occupied zone; and a fight might result, as the general was notoriously a spirited soldier, a man of 60 who lowers himself 45 meters over a cliff by means of a rope—that is how he escaped from Konigstein.

Fifth phase: According to Lahousen's (Generalmajor Erwin von Lahousen) explanation in Berlin, Canaris desire to transfer the matter to the Secret State Police, which Lahousen said was done as a result of representations from the departmental heads, was because I asked again how matters stood with Giraud and he wanted to get rid of this awkward mission. Canaris came to me and asked if he could pass it on to the Reich Security Main Office or to the police. I said yes, because the Fuehrer had already told me repeatedly that he wanted to hand it over to Himmler. Next phase: I wanted to warn Canaris some time later, when Himmler came to see me and confirmed that he had received orders from Hitler to have Giraud and his family watched unobtrusively and that I was to stop Canaris from taking any action in the case. He had been told that Canaris was working along parallel lines. I immediately agreed.

Now we come to the phase which Lahousen has described at length. I had asked about "Gustav" and similar questions. I wanted to direct Canaris immediately to stop all his activities in the matter, as Hitler had confirmed the order. What happened in Paris according to Lahousen's detailed reports, that excuses were sought, et cetera, that the matter was thought to be very mysterious, that is, Gustav as an abbreviation for the G in Giraud, all this is fancy rather than fact. I had Canaris summoned to me at once, for he was in Paris and not in Berlin. He had done nothing at all, right from the start. He was thus in a highly uncomfortable position with regard to me for he had lied to me. When he came I said only, "You will have nothing more to do in this matter; keep clear of it." Then came the next phase: The general's escape without difficulty to North Africa by plane, which was suddenly reported—if I remember correctly—before the invasion of North Africa by the Anglo-American troops. That ended the business. No action was ever taken by the Counterintelligence whom I had charged to watch him, or by the police; and I never even used the words to do away with the general. Never!

The final phase of this entire affair may sound like a fairy tale, but it is true nevertheless. The general sent a plane from North Africa to Southern France near Lyons in February or March 1944, with a liaison officer who reported to the Counterintelligence and asked if the general could return to France and what would happen to him on landing in France. The question was turned over to me. Generaloberst Jodl is my witness that these things actually happened. The chief of the Counterintelligence Office involved in this matter was with me. The answer was: "Exactly the same treatment as General Weygand who is already in Germany. There is no doubt that the Fuehrer will agree." Nothing actually did happen, and I heard no more about it. But these things actually happened. ...

I had only an unobtrusive watch kept on the family's residence in order to receive information of any visit which he might have planned. But no steps of any kind were ever taken against the family. It would have been foolish in this case. ...I never gave such an order (to kill Giraud), unless the phrase "We must have him back, dead or alive" may be considered of weight in this respect. I never gave orders that the general was to be killed or done away with, or anything of the kind. Never.

From The Unseen War in Europe by John H. Waller: (Admiral) Canaris had been under orders from Hitler to spare no effort in tracking down Giraud and having him killed before he could cause difficulties for Vichy and the Germans. This project was known as Operation Gustav. But despite prodding from General Keitel and a bounty of one hundred thousand marks offered to the public by Hitler for information of Giraud's whereabouts, the French fugitive was able to evade capture by the Abwehr. Canaris in fact had no intention of capturing Giraud. From the beginning he would not be party to the French General's assassination and let Keitel know that the operation was not the sort of thing the Abwehr would undertake. He protested that unlike the SD, his organization was not a band of assassins. Canaris had, however, made an effort to discover the general's intentions before he made his escape.

Because of Hitler's intense interest in this matter, the Abwehr dispatched an agent to get in touch with Giraud and try to ascertain whether the general believed the Americans and British would try to land somewhere in North or northwestern Africa in early 1943 and whether he intended to plan any significant role in the future. The agent was also instructed to discover and comment on the prospect of French resistance to such landings. Churchill showed great concern about Giraud when this German message, broken at Bletchley in late September 1942, was shown to him. He scrawled in the margin of the text that Giraud should be duly warned he might be questioned by a German-sent agent about his knowledge of Allied intentions to open a second front and his own intentions in French North Africa. Canaris was playing a dangerous game in defying and evading Hitler's order to kill Giraud. His inaction could not be easily explained if he were found out, but he seized on Heydrich's death to lie to Keitel, telling him that he had turned over the operation to the late SD chief. It had therefore been Heydrich, now unable to defend himself, who had to bear responsibility for letting Giraud slip through the SS dragnet and collaborate with the Allies in North Africa.

At the same time machine gunners, without any warning, shot at inhabitants who approached their burning houses; some of the residents were bound, sprayed with gasoline and thrown into the burning buildings...In their insane fury against the Soviet people, which was caused by defeats suffered at the front, the commanding general of the 2d German Panzer Army, General Schmidt, and the commander of the Orel administrative region and military commander of that city, Major General Hamann, had created special demolition commandos for the destruction of towns, villages, and collective farms of the Orel region. These commandos, plunderers, and arsonists destroyed everything in the path of their retreat. They destroyed cultural monuments and works of art of the Russian people, burned down cities, towns, and villages.

May 1, 1942: People's Commissar of Defense Stalin releases Order No. 130:

The Hitlerite imperialists have occupied vast territories in Europe, but they have not broken the will to resistance of the European peoples. The struggle of the enslaved peoples against the regime of the German-fascist highwaymen is beginning to assume general scope. Sabotage at war plants, the blowing up of German ammunition stores, the wrecking of German troop trains and the killing of German soldiers and officers have become everyday occurrences in all the occupied countries. All Yugoslavia and the German-occupied Soviet areas are swept by the flames of partisan warfare. All these circumstances have led to a weakening of the German rear, which means the weakening of fascist Germany as a whole...

May 5, 1942: Jodl finally convinces Hitler to, in effect, cancel the infamous Commissar Order (See June 6, 1941). (Maser)

July 1-27, 1942: The advance of Axis troops on Alexandria is blunted by the Allies at the First Battle of El Alamein.

From Keitel's SBS interview: In North Africa we had seen for the first time the strength of the Allied Air Force and its effective operations during the battle of El Alamein. It was there for the first time that we felt the effect of an air force against ground operations. That strength was not expected. It came as a surprise." ...

Q: What reasons lie behind the failure of Rommel to achieve success in Cyrenaica and Libya? What prevented adequate supplies from reaching Rommel?

Keitel: It was the breakdown of the supply system. The reason for it was that the Italians did not live up to the minimum expectations a far as transportation and the security of transport was concerned. Therefore, they were not able to bring up the bare necessities of supplies.

The Operational Staff of the Navy (SKL) applied on the 29th May for permission to attack the Brazilian sea and air forces. The SKL considers that a sudden blow against the Brazilian war ships and merchant ships is expedient at this juncture because defense measures are still incomplete, because there is the possibility of achieving surprise, and because Brazil is actually fighting Germany at sea.

July 28, 1942: From Stalin's Order (#227) for the Defense of the Soviet Union:

August 6, 1942: To the Commandant de la Police de Surete et du SD:

From Keitel's IMT testimony: As I have already described in connection with the Nacht und Nebel Decree, sabotage acts, the dropping of agents by parachute, the parachuting of arms, ammunition, explosives, radio sets and small groups of saboteurs reached greater and greater proportions. They were dropped at night from aircraft in thinly populated regions. This activity covered the whole area governed by Germany at that time. It extended from the west over to Czechoslovakia and Poland, and from the East as far as the Berlin area. Of course, a large number of the people involved in these actions were captured and much of the material was taken. This memorandum was to rally all offices, outside the Wehrmacht, as well, police and civilian authorities, to the service against this new method of conducting the war, which was, to our way of thinking, illegal, a sort of "war in the dark behind the lines."