June 7, 1945: Justice Jackson sends off a progress report to President Truman:

July 16, 1945: Since May, the Allies have been collecting Nazis and tossing the high-ranking ones into a former hotel in Mondorf, Luxembourg, affectionately referred to as 'Ashcan.' On this day, Ashcan's commander, Colonel Burton C. Andrus, takes representatives of the world's Press on a tour of the facility to squash rumors that the prisoners are living the high-life. "We stand for no mollycoddling here," Andrus proclaims. "We have certain rules and the rules are obeyed... ...they roll their own cigarettes." (Tusa)

July 19, 1945 International Conference on Military Trials: From the minutes of this days Conference Session:

July 31, 1945: From the letters of Thomas Dodd, Executive Trial Counsel for the Prosecution at Nuremberg:

August 8, 1945: The London Agreement is signed.

August 12, 1945: Justice Jackson releases a statement to the American press:

August 12, 1945: Colonel Andrus and his 15 Ashcan prisoners are loaded onto a US C-47 transport plane bound for Nuremberg. As they fly above Germany, Goering continually points out various geographical features below, such as the Rhine, telling Ribbentrop to take one last look as he is unlikely to ever get the opportunity again. Streicher becomes air-sick. (Tusa)

August 25, 1945 International Conference on Military Trials: Representatives of the Big Four (Jackson, Fyfe, Gros, and Niktchenko), agree on a list of 22 defendants, 21 of which are in custody. The 22nd, Martin Bormann, is presumed to be in Soviet custody, but Niktchenko cannot confirm it. The list is scheduled to be released to the press on August 28. (Conot)

August 28, 1945 International Conference on Military Trials: Just in time to delay the release of the names of the final 22, Niktchenko informs the other three Allied representatives that, unfortunately, Bormann is not in Soviet custody. However, he announces that the valiant Red Army has captured two vile Nazis, Erich Raeder, and Hans Fritzsche, and offers them up for trial. Though neither man was on anyone's list of possible major defendants, it emerges that their inclusion has become a matter of Soviet pride; Raeder and Fritzsche being the only two ranking Nazis unlucky enough to have been caught in the grasp of the advancing Russian bear. (Conot)

August 29, 1945 International Conference on Military Trials: With the additions of Raeder and Fritzsche, the final list of 24 defendants is released to the press. Bormann, though not in custody (or even alive), is still listed. (Conot, Taylor)

August 29, 1945: The Manchester Guardian reacts to the release of the list of defendants:

August 30, 1945: The Glasgow Herald reacts to the release of the list of defendants:

September 17, 1945: From the letters of Thomas Dodd:

October 5, 1945: Andrus loses his first German prisoner to suicide; Dr Leonard Conti, Hitler's Head of National Hygiene.

October 19, 1945: British Major Airey Neave presents each defendant in turn with a copy of the indictment. Gilbert, the Nuremberg psychologist, asks the accused to write a few words on the documents margin indicating their attitude toward the development. Funk: "If I have been made guilty of the acts ... through error or ignorance, then my guilt is a human tragedy and not a crime." (Tusa)

October 25, 1945: Andrus loses yet another Nazi as Defendant Dr Robert Ley, Hitler's head of the German Labor Front (Deutsche Arbeitsfront, DAF), commits suicide in his Nuremberg cell. Scorecard: There are now officially 23 indicted defendants; 22 of these are actually alive and in Allied custody.

October 29, 1945: Only seven of the defendants have obtained counsel by this date. Major Neave, while serving the Indictment to the defendants, had offered to assist them in obtaining counsel. Note: Eighteen of the forty-eight German lawyers who eventually participate in the trial will have Nazi backgrounds. (Conot, Maser, Taylor)

1945: Prior to the trial, the defendants are given an IQ test. Administered by Dr. Gilbert, the Nuremberg Prison psychologist, and Dr. Kelly, the psychiatrist, the test includes ink blots and the Wechsler-Bellevue test. Funk: 124. Note: After the testing, Gilbert comes to the conclusion that all the defendants are "intelligent enough to have known better." Andrus is not impressed by the results: "From what I've seen of them as intellects and characters I wouldn't let one of these supermen be a buck sergeant in my outfit." (Tusa)

November 19, 1945: After a last inspection by Andrus, the defendants are escorted handcuffed into the empty courtroom and given their assigned seats. Schacht, having been assigned the seat next to Streicher, is somehow able to switch places with Funk. For the first time ever, Funk, a constant fidgeter, now precedes Schacht. During the trial Schacht will ignore Funk's attempts at conversation, pretending disinterest with the entire affair. (Speer, Conot, Tusa)

November 19, 1945: The day before the opening of the trial, a motion is filed on behalf of all defense counsel:

November 20, 1945 Nuremberg Tribunal: On day 1 of the historic trial, the prosecutors take turns reading the Indictment in court. Unfortunately, no one had given any thought to the prisoners lunch break, so, for the first and only time during 218 days of court, the defendants eat their midday meal in the courtroom itself. This is the first opportunity for the entire group to mingle, and though some know each other quite well, their are many who've never met. (Tusa, Conot)

November 21, 1945 Nuremberg Tribunal: On day 2, the defendants enter their pleas: "The President: I will now call upon the defendants to plead guilty or not guilty to the charges against them. They will proceed in turn to a point in the dock opposite to the microphone ... Funk: "I declare myself not guilty."

November 21, 1945 Nuremberg Tribunal: Immediately following the pleas of the defendants, Justice Jackson delivers his opening statement:

November 22, 1945 Nuremberg Tribunal: Major Frank Wallis, Assistant Trial Counsel for the United States, presents the case known as the Common Plan or Conspiracy:

November 29, 1945: The prosecution presents as evidence a film shot by US troops as they were liberating various German concentration camps. That evening in his cell, Funk is incapable of coherent conversation. Tears run down his face as he mumbles, "Terrible, terrible..." Later he will deny any knowledge to Gilbert: "Do you think I had the slightest notion about gas wagons and such horrors?" He then reminded Gilbert that it was he, Funk, who had saved the French franc from devaluation during German occupation. (Heydecker, Tusa)

December 11, 1945 Nuremberg Tribunal: The Chicago Daily News describes Funk in court: "...with a whining expression on his round, Humpty-Dumpty face, Funk, the smallest of the defendants, resembles a gnome who has lost his last friend."

December 14, 1945 Nuremberg Tribunal: The tendency of some of the defendants to denounce, or at least criticize Hitler on the stand, leads to an outburst by Göring during lunch: "You men knew the Führer. He would have been the first one to stand up and say 'I have given the orders and I take full responsibility.' But I would rather die ten deaths than to have the German sovereign subjected to this humiliation." Keitel fell silent, but Frank was not crushed: "Other sovereigns have stood before courts of law. He got us into this." Funk, Dönitz, Keitel and Schirach suddenly get up and leave Göring's table." (Tusa)

December 20, 1945 Nuremberg Tribunal: After this days session, the trial adjourns until Wednesday, the 2nd of January. (Conot)

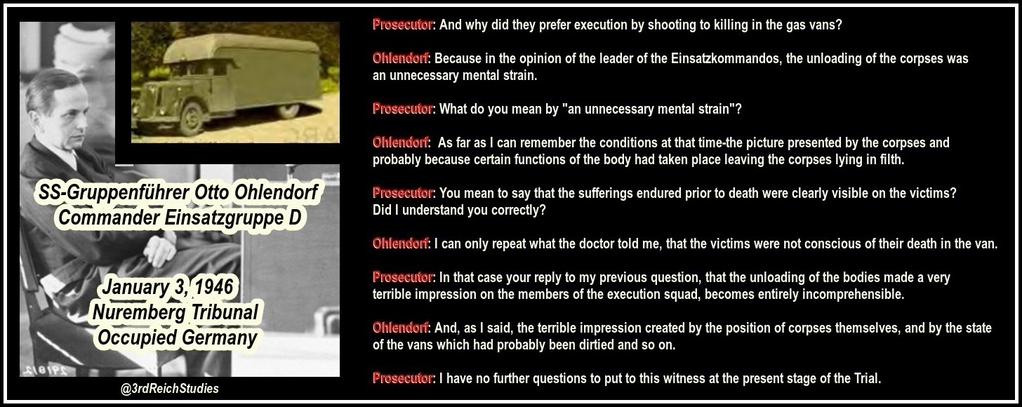

January 3, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On day 26, Otto Ohlendorf testifies for the defense concerning the murder of hundreds of thousands of Jews by the Einsatz groups. (Gilbert)

January 11, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On day 32 of deliberations, Lieutenant Bernhard Meltzer, Assistant Trial Counsel for the United States, presents the case against Funk:

January 11, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On Day 32 of deliberations, the prosecution calls Dr. Franz Blaha, former prisoner of Dachau, to the stand.

February 15, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: Colonel Andrus tightens the rules for the defendants by imposing strict solitary confinement. This is part of a strategy designed to minimize Göring's influence among the defendants. (Tusa)

February 16, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: The Daily Mail describes Funk in court: "...yellow, heavy-jowled, he crouches over the dock and scratches his chin with a curiously Simian gesture."

January 28, 1946: From the diary of the British Alternate Judge, Mr. Justice Birkett:

February 22, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: In a further move to minimize his influence, Göring is now required to eat alone during the courts daily lunch break. The other defendants are split up into groups, with Funk sharing a table with Fritzsche, Schirach and Speer in the so-called Youth Lunchroom. (Speer, Tusa)

April 8, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On Day 102, Funks defense cross-examines Hans Heinrich Lammers.

May 1, 1946 From the letters of Thomas Dodd:

From Justice at Nuremberg by Robert E. Conot: Walter Funk followed Schacht into the witness stand as he had succeeded him in the Hitler administration; and there could have been no starker example of the manner in which men of talent had been precipitated out of the regime in favor of sycophantic sybarites. Slumping down into his chair as if attempting to hide in it, the flabby, hypochondriac Funk mumbled and slurred his words so badly that the interpreters and stenographers had difficulty understanding him. Parker called him "a pitiful little man in bad health"—precisely the impression Funk wanted to create . . . .

Like Göring, Funk had been addicted to jewelry and high living, and carried a watch made out of a glittering dollar gold piece. He loved cigars, drinking, and all-night parties. A talking compendium of risqué jokes, Funk had attempted to pass himself off as one of the world's great lechers. These sexual pretensions had caused considerable merriment in the higher Nazi echelons, where he had been well known as a homosexual. When, at the time of the Fritsch crisis, the Berlin police president, Helldorf, had informed Goebbels that he also had a dossier on Funk, Goebbels had shrugged. "The only thing that could be done," the propaganda minister had said, "was to arrange an automobile accident, and that would be no way to treat an alte Kaempfer (old fighter) like Funk." . . . .

When, in mid-October, Funk had been brought to Nuremberg from the hospital where he had been treated for his bladder infection, he had complained interminably to his interrogator, Murray Gurfein: "I am stuck in a very cold cell, and if this continues for two or three days, we shall have the old trouble all over again. I must request you to deal with me softly, as I am very ill."

May 3, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On day 120 of deliberations, Funk begins his testimony:

May 4, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On day 121 of deliberations, Funk testifies on his own behalf:

Funk: I never belonged to any organization of the Party, neither SA nor SS, nor any other organization; and as I have already said, I did not belong to the Leadership Corps.

Dr. Sauter: You did not belong to the Leadership Corps?

Funk: No.

Dr. Sauter: You know, Dr. Funk, that the Party functionaries, that is, the Party veterans, and so forth, met annually in November at Munich. You have yourself seen a film showing this anniversary meeting. Were you ever invited to these gatherings on 8 and 9 November?

Funk: I do not know whether I received invitations; it is possible. But I have never been at such a gathering, for these meetings were specially intended for old Party members and the Party veterans, in commemoration of the March on the Feldherrnhalle. I never participated in these gatherings, as I was averse to attending large gatherings. During all this time I attended a Party rally only once, just visiting one or two functions. Mass gatherings always caused me physical pain...

May 6, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On day 122 of deliberations, Funk is cross-examined by the prosecution:

Witness, then in addition to these offices of yours which we have discussed up to now, you finally had a further office as successor of Dr. Schacht, namely, that of Plenipotentiary General for Economy. Can you give us some details of your view in this connection in order to clarify your situation, your activity, and your achievements?

Funk: This of all the positions I had was the least impressive. As the Reich Marshal correctly stated, and as Dr. Lammers confirmed, it existed merely on paper...

May 6, 1946 From the letters of Thomas Dodd:

May 7, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On day 123 of deliberations, Funk is cross-examined by the prosecution:

Funk: No, I know nothing about the date. I do not know when these things happened. I had nothing to do with them. It is all news to me that the Reichsbank was concerned with these things to this extent.

Mr. Dodd: Then I take it you want to stand on an absolute denial that at any time you had any knowledge of any kind about these transactions with the SS or their relationship to the victims of the concentration camps. After seeing this film, after hearing Puhl's affidavit, you absolutely deny any knowledge at all?

Funk: Only as far as I have mentioned it here.

Mr. Dodd: I understand that; there was some deposit of gold made once, but no more than that. That is your statement. Let me ask you something, Mr. Funk . . . .

Funk: Yes; that these things happened consistently is all news to me.

Mr. Dodd: All right. You know you did on one occasion at least, and possibly two, break down and weep when you were being interrogated, you recall, and you did say you were a guilty many and you gave an explanation of that yesterday. You remember those tears. I am just asking you now; I am sure you do. I am just trying to establish the basis here for another question. You remember that happened?

Funk: Yes.

Mr. Dodd: And you said, "I am a guilty man." You told us yesterday it was because you were upset a little bit in the general situation. I am suggesting to you that is it not a fact that this matter that we have been talking about since yesterday has been on your conscience all the time and that was really what is on your mind, and it has been a shadow on you ever since you have been in custody? And is it not about time that you told the whole story?

Funk: I cannot tell more to the Tribunal than I have already said, that is the truth...

May 7, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On Day 123, Funk's defense calls Dr Franz Hayler to the stand.

May 8, 1946 From the letters of Thomas Dodd:

June 26, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On day 164, Fritzsche testifies on his own behalf:

Fritzsche: No. There were many offices between him and me at first, and still a few later on. This is the first times here in the dock, that I am without official superiors.

Dr Fritz: By the way, whom of the defendants did you know or with whom did you have official or personal relations?

Fritzsche: I had two or three official conversations, shortly after 1933, with Funk, who was then State Secretary in the Propaganda Ministry, mainly dealing with economic and organizational matters. I discussed with him the financial plans for the reorganization of the news service. Then, I once had a talk with Großadmiral Dönitz on a technical matter. I called on Seyss-Inquart in The Hague, and on Papen in Istanbul. I knew all the others only by sight and' first made their personal acquaintance during the Trial.

Dr Fritz: How about Hitler?

Fritzsche: I never had a conversation with him. In the course of 12 years, however, I saw him, of course, several times at the Reichstag on big occasions or receptions. Once I was at his headquarters and was invited to dinner with a large number of other people. Otherwise, I received. instructions from Hitler only through Dr. Dietrich or his representative or through Dr. Goebbels and his various representatives...

June 28, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On day 166, Fritzsche testifies on his own behalf:

Fritzsche: It had existed for quite some time, at least up until March 1933, when it was a branch of the Foreign Of lice. From then on it became a branch of the Propaganda Ministry, and it had a dual mission to carry on: First of all to be the Press Department of this Ministry and secondly, to continue functioning as the Press Department for the Reich Government.

Sauter: Witness, can you tell me who, beginning with March of 1933—that is, from the incorporation of the Press Department into the Propaganda Ministry—was the chief of this Press Department and, for all practical purposes, was the chief of the press system? Was that Funk or was it someone else?

Fritzsche: No, that was Ministerial Counselor Jahnke, successor to Ministerial Director Berndt. This Press Department was then divided into three sections: German press ...

Sauter: I am not interested in that, Witness, I am interested only in knowing whether the chief of this department was the Defendant Funk or whether it is correct to say that he had nothing to do with these matters.

Fritzsche: Nominally, of course, he was the chief...

From The Nuremberg Trial by Ann and John Tusa: Once Funk's career was examined more closely, it was impossible to avoid the conclusion that the indictment against him had confused formal position with actual authority. When the prosecutors had drawn up the indictment they had been too ignorant of the hierarchy and personalities of the Nazi regime to assess the real importance of several of the defendants. They had exaggerated Funks role . . . .

A tougher man would have spotted and seized the opportunities left for his defense. A Göring or a Schacht would have had a field day at the expense of the prosecution, but Funk lacked the personality for a fight. He was one of Andrus's least favorite prisoners, "always whimpering and whining," said the Colonel; and to lower his opinion further, scruffy in appearance and slovenly in the upkeep of his cell. Funk's excuse for whimpering and whining was his health; he was diabetic and had had bouts of kidney and bladder trouble. But as Gilbert told Andrus: "His complaints were far out of proportion with the physical findings"; a once cheerful gadabout had become in prison "hypochondriac and forlorn." A more justifiable complaint perhaps from Funk was that he had to sit in the dock every day next to Streicher. He regarded this as a punishment; most people would . . . .

By the time the court had heard the self-justifications of Funk and the two witnesses--all three hurling blame at each other--Dean reckoned that "the amount of perjury committed has been remarkable even for Nuremberg." None of it had concealed Funk's guilt on this charge at least. Would his seeming evasiveness or lying over other charges lead the Tribunal to conclude he was guilty there too? Certainly nothing Funk had done for himself in the witness box had shaken the rather flimsy case against him.

July 17, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: Funk's defense sends a letter to the President of the International Military Tribunal:

The statement by the Defendant Funk under cross-examination was due to faulty recollection, because of the fact that these cross-examination questions of the Prosecution had completely surprised and greatly disturbed Funk. Immediately after the examination of the witness Puhl, Funk informed me of his mistake and asked me to correct his factually incorrect statement on this point, since he himself would have no opportunity to do so. I put forward this request of the Defendant Funk, and I take the liberty of informing the President of the correct state of affairs. The Defendant Funk agrees with this correction by co-signing this letter.

July 12, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On day 177 of deliberations, Dr. Fritz Sauter, defense counsel for Funk, delivers his final speech:

From The Anatomy of the Nuremberg Trials by Telford Taylor: Funk's counsel was Dr. Fritz Sauter, a tall, rather excitable man who prefaced his questions with explanatory remarks calculated to give witnesses more than a hint of the answers he expected . . . . Dr. Sauter began (his final speech) by announcing that his task was "especially dry and prosaic." He was right, but a large part of the cause was Sauter himself, whose dense and unorganized presentation was well nigh incomprehensible. Funk's own testimony, and his cross-examination by Dodd had left him vulnerable on a number of scores, culminating in the Reichsbank's receipt of gold teeth and other mementos of their shocking source. Sauter's argument accomplished nothing in Funk's behalf. His best card was that Funk was so flabby and scared that it was hard for anyone to take him for a murderer.

July 12, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: Funk reacts to the closing remarks of the defense: "I don't see how the court can acquit a single one of us."

July 26, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On Day 187 of deliberations, US Justice Jackson details Prosecutions closing arguments against Funk.

While a credulous world slumbered, snugly blanketed with perfidious assurances of peaceful intentions, the Nazis prepared not as before for a war but now for the war. The Defendants Göring, Keitel, Raeder, Frick, and Funk, with others, met as the Reich Defense Council in June of 1939. The minutes, authenticated by Göring, are revealing evidences of the way in which each step of Nazi planning dovetailed with every other. These five key defendants, 3 months before the first Panzer unit had knifed into Poland, were laying plans for "employment of the population in wartime," and had gone so far as to classify industry for priority in labor supply after "5 million servicemen had been called up." They decided upon measures to avoid "confusion when mobilization takes place," and declared a purpose "to gain and maintain the lead in the decisive initial weeks of a war."

They then planned to use in production prisoners of war, criminal prisoners, and concentration camp inmates. They then decided on "compulsory work for women in wartime." They had already passed on applications from 1,172,000 specialist workmen for classification as indispensable, and had approved 727,000 of them. They boasted that orders to workers to report for duty "are ready and tied up in bundles at the labor offices." And they resolved to increase the industrial manpower supply by bringing into Germany "hundreds of thousands of workers" from the Protectorate to be "housed together in hutment’s". It is the minutes of this significant conclave of many key defendants which disclose how the plan to start the war was coupled with the plan to wage the war through the use of illegal sources of labor to maintain production. Hitler, in announcing his plan to attack Poland, had already foreshadowed the slave-labor program as one of its corollaries when he cryptically pointed out to the Defendants Goering, Raeder, Keitel, and others that the Polish population "will be available as a source of labor" . . . .

At a meeting held on 12 November 1938, 2 days after the violent anti-Jewish pogroms instigated by Goebbels and carried out by the Party Leadership Corps and the SA, the program for the elimination of Jews from the German economy was mapped out by Göring, Funk, Heydrich, Goebbels, and the other top Nazis. The measures adopted included confinement of the Jews in ghettos, cutting off their food supply, "Aryanizing" their shops, and restricting their freedom of movement . . . . As Minister of Economics Funk accelerated the pace of rearmament, and as Reichsbank president banked for the SS the gold teeth fillings of concentration camp victims--probably the most ghoulish collateral in banking history.

July 27, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On day 188 of deliberations, Sir Hartley Shawcross, Chief Prosecutor for the United Kingdom, details Prosecutions closing arguments:

Hitler's plan for Poland, revealed to Schirach and Frank, was as follows—I quote: "The ideal picture is this: A Pole may possess only small holdings in the Government General which will to a certain extent provide him and his family with food. The money required by him for clothes, . . . et cetera! he must earn in Germany by work. The Government General must become a center for supplying unskilled labor, particularly agricultural labor. The subsistence of these workmen will be fully guaranteed because they can always be made use of as cheap labor." That policy, of course, was a short-term policy, the real aim being the elimination of the Eastern peoples...

July 29, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On day 189, M. Charles Dubost, Deputy Chief Prosecutor for the French Republic, details Prosecutions closing arguments:

July 29, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On day 189 of deliberations, General Rudenko, Chief Prosecutor for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, details Prosecutions closing arguments:

August 5, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: Very late in the trial, day 195, the prosecution introduces an affidavit by Oswald Pohl that is extremely damaging to Funk:

The connection of my office with the Reichsbank with regard to textiles of persons who had been killed in concentration camps was instituted in the year 1941 or 1942. At that time I received the order from the Reichsführer SS and the Chief of the German Police, Heinrich Himmler, who was my chief, to get in touch with the Reich Minister of Economics, Walter Funk, to obtain a higher allotment of textiles for SS uniforms. Himmler instructed me to demand from Funk that we receive preferential treatment. The Minister of Economics was receiving from the concentration camps a large delivery of textiles. These textiles had been collected in the extermination camp Auschwitz, and other extermination camps, and then delivered to the competent offices for used textiles.

As a result of this order received from my superior, Himmler, I visited the Reich Minister of Economics Funk in his offices. I waited only a short while in his anteroom and then met him alone in his private office. I informed Funk of my instructions that I was to ask him for more textiles for SS uniforms, since we had been able to deliver such large quantities of old textiles due to the actions against Jews. The meeting lasted around 10 minutes. It was openly discussed that we perhaps deserved privileged treatment on account of the delivery of old clothes of dead Jews. It was a friendly conversation between Funk and myself and he said to me that he would settle the matter favorably with the officials concerned. How the subsequent settlement between Funk and his subordinates and my subordinates was handled in detail, I do not know.

The second business deal between Walter Funk and the SS concerned the delivery of articles of value of dead Jews to the Reichsbank. It was in the year 1941 or 1942, when large quantities of articles of value, such as jewelry, gold rings, gold fillings, spectacles, gold watches, and such had been collected in the extermination camps. These valuables arrived packed in cases to the WVHA in Berlin. Himmler had ordered us to deliver these things to the Reichsbank. I remember that Himmler explained to me that negotiations concerning this matter had been conducted with the Reichsbank, that is, Herr Funk.

As a result of an agreement that my chief had made, I discussed with the Reichsbank Director, Emil Puhl, the manner of delivery. In this conversation no doubt remained that the objects to be delivered were the jewelry and valuables of concentration camp inmates, especially of Jews, who had been killed in extermination camps. The objects in question were rings, watches, eyeglasses, ingots of gold, wedding rings, brooches, pins, frames of glasses, foreign currency, and other valuables. Further discussions concerning the delivery of these objects took place between my subordinates and Puhl and other officials of the Reichsbank. It was an enormous quantity of valuables, since there was a steady flow of deliveries for months and years.

A part of these valuables from people killed in death camps I saw myself when Reichsbank President Funk and Vice President Puhl invited us to an inspection of the Reichsbank vaults and afterward to lunch. I do not remember exactly whether this was in 1941 or in 1942, but I do remember that I already knew Funk personally at that time from the textile deals that I have described above. Vice President Puhl and several other gentlemen of my staff went to the vaults of the Reichsbank. Puhl himself led us on this occasion and showed us gold ingots and other valuable possessions of the Reichsbank. I remember exactly that various chests containing objects from concentration camps were opened. At this point Puhl or Waldhecker, who accompanied him, stated in my presence and in the presence of the members of my staff that a part of these valuables had been delivered by our office.

After we had inspected the various valuables in the vaults of the Reichsbank, we went upstairs to a room in order to have lunch with Reichsbank President Funk; it had been arranged that this should follow the inspection. Besides Funk and Puhl, the members of my staff were present; we were about 10 to 12 persons. I sat beside Funk and we talked, among other things, about the valuables that I had seen in his vaults. On this occasion it was clearly stated that a part of the valuables which we had seen came from concentration camps.

August 12, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On day 201 of deliberations, Funks defense protests the late inclusion of the Oswald Pohl Affidavit:

August 12, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On day 205 of deliberations, Funk returns to the stand to respond to the Pohl Affidavit:

But Pohl's assertion that he said something to me about dead Jews from whom these deliveries were supposed to have come, these goods turned in by the SS as old material, is monstrous. That was supposed to have been in 1941, perhaps 1942. That Pohl should tell me, whom he was seeing for the first time, a secret which was closely guarded up to the end, is in itself incredible. But he had no reason to mention dead Jews to me when he told me that big deliveries would be arriving from the SS. It seemed perfectly plausible to me that in the large domain, of the SS, where hundreds of thousands of men were housed in barracks, and were clothed by the State, there must constantly have been much old material...

August 30, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On day 216 of deliberations, the defendants make their final statements.

Now, horrible crimes have become known here, in which the offices under my direction were partly involved. I learned this here in court for the first time. I did not know of these crimes, and I could not have known them. These criminal deeds fill me, like every German, with deep shame. I have examined my conscience and memory with the utmost care, and I have told the Court frankly and honestly everything that I knew and have concealed nothing.

As far as the deposits of the SS in the Reichsbank are concerned, I only acted in performance of the official duties incumbent on me as President of the Reichsbank. According to law, the acceptance of gold and foreign currency was one of the business tasks of the Reichsbank. The fact that the confiscation of these assets was taking place through the SS agencies subordinate to Himmler could not arouse any suspicion in me. The entire police system, the border control, and especially the search for foreign currency in the Reich and in all occupied areas were under Himmler, but I was equally deceived and imposed upon by Himmler.

Until the time of this Trial, I did not know and did not suspect that among the assets delivered to the Reichsbank there were enormous quantities of pearls, precious stones, jewelry, gold objects, and even spectacle frames, and—horrible to say—gold teeth. That was never reported to me, and I never noticed it either. I never saw these things. But until this Trial I also knew nothing of the fact that millions of Jews were murdered in concentration camps or by the Einsatzkommandos in the East. Never did a single person say even one word to me about these things. The existence of extermination camps of this kind was totally unknown to me. I did not know a single one of these names. I have never set foot in a concentration camp either.

I, too, assumed that some of the gold and foreign currency that was deposited in the Reichsbank came from concentration camps, and I frankly stated this fact from the beginning in all of my interrogations. But according to German law everyone was obliged to deliver these assets. Apart from that, the kind and quantity of these shipments from the SS were never made known to me. But how was I even to suspect that the SS had acquired these assets by desecrating corpses? If I had known of these horrible circumstances, my Reichsbank would never have accepted these assets for storage and conversion into money. I would have refused, even risking the danger that it might have cost me my head.

If I had known of these crimes, Your Honors, I would not be sitting in the defendant's dock today, you may be convinced of that. In that case the grave would have been better for me than this tormented life, this life full of suspicions, slanders, and vulgar accusations. Not a single human being has ever lost his life because of any measures decreed by me. I have always respected the property of others. I have always tried to help people in need and, as far as it lay within my power, to bring happiness and Joy into their lives. And for that, many will be grateful to me and remain grateful.

Human life consists of error and guilt. I, too, have made many mistakes; I, too, have let myself be deceived in many things and I frankly acknowledge, I admit, that I have let myself be deceived all too easily, and in many ways have been too unconcerned and too gullible. Therein I see my guilt, but consider myself free from any criminal guilt that I am supposed to have incurred in discharging my official duties. In that respect, my conscience is just as clear today as on the day when I entered this courtroom 10 months ago for the first time.

September 2, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: As the defendants await the courts judgment, Colonel Andrus somewhat relaxes the conditions of confinement, allowing those prisoners with wives or children limited visitation.

September 29, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: From notes by Dr. Pflücker, Nuremberg Prison's German Doctor:

September 30, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On the penultimate day of this historic trial, the final judgments are read in open court:

Crimes against Peace: Funk became active in the economic field after the Nazi plans to wage aggressive war had been clearly defined. One of his representatives attended a conference on 14 October 1938, at which Göring announced a gigantic increase in armaments and instructed the Ministry of Economics to increase exports to obtain the necessary exchange. On 28 January 1939, one of Funk's subordinates sent a memorandum to the OKW on the use of prisoners of war to make up labor deficiencies which would arise in case of mobilization. On 30 May 1939, the Under Secretary of the Ministry of Economics attended a meeting at which detailed plans were made for the financing of the war.

On 25 August 1939, Funk wrote a letter to Hitler expressing his gratitude that he was able to participate in such world-shaking events; that his plans for the "financing of the war," for the control of wage and price conditions and for the strengthening of the Reichsbank had been completed; and that he had inconspicuously transferred into gold all foreign exchange resources available to Germany. On 14 October 1939, after the war had begun, he made a speech in which he stated that the economic and financial departments of Germany working under the Four-Year Plan had been engaged in the secret economic preparation for war for over a year.

Funk participated in the economic planning which preceded the attack on the USSR. His deputy held daily conferences with Rosenberg on the economic problems that would arise in the occupation of Soviet territory. Funk himself participated in planning for the printing of ruble notes in Germany prior to the attack to serve as occupation currency in the USSR. After the attack he made a speech in which he described plans he had made for the economic exploitation of the "vast territories of the Soviet Union" which were to be used as a source of raw material for Europe. Funk was not one of the leading figures in originating the Nazi plans for aggressive war. His activity in the economic sphere was under the supervision of Göring as Plenipotentiary of the Four-Year Plan. He did, however, participate in the economic preparation for certain of the aggressive wars, notably those against Poland and the Soviet Union, but his guilt can be adequately dealt with under Count Two of the Indictment.

War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity: In his capacity as Under Secretary in the Ministry of Propaganda and Vice-Chairman of the Reich Chamber of Culture, Funk had participated in the early Nazi program of economic discrimination against the Jews. On 12 November 1938, after the pogroms of November, he attended a meeting held under the chairmanship of Goering to discuss the solution of the Jewish problem and proposed a decree providing for the banning of Jews from all business activities, which Goering issued the same day under the authority of the Four-Year Plan. Funk has testified that he was shocked at the outbreaks of 10 November, but on 15 November he made a speech describing these outbreaks as a "violent explosion of the disgust of the German people, because of a criminal Jewish attack against the German people," and saying that the elimination of the Jews from economic life followed logically their elimination from political life.

In 1942 Funk entered into an agreement with Himmler under which the Reichsbank was to receive certain gold and jewels and currency from the SS and instructed his subordinates, who were to work out the details, not to ask too many questions. As a result of this agreement the SS sent to the Reichsbank the personal belongings taken from the victims who had been exterminated in the concentration camps. The Reichsbank kept the coins and bank notes and sent the jewels, watches, and personal belongings to Berlin municipal pawnshops. The gold from the eyeglasses and gold teeth and fillings were stored in the Reichsbank vaults. Funk has protested that he did not know that the Reichsbank was receiving articles of this kind. The Tribunal is of the opinion that he either knew what was being received or was deliberately closing his eyes to what was being done.

As Minister of Economics and President of the Reichsbank, Funk participated in the economic exploitation of occupied territories. He was President of the Continental Oil Company, which was charged with the exploitation of the oil resources of occupied territories in the East. He was responsible for the seizure of the gold reserves of the Czechoslovakian National Bank and for the liquidation of the Yugoslavian National Bank. On 6 June 1942, his deputy sent a letter to the OKW requesting that funds from the French occupation cost fund be made available for black market purchases. Funk's knowledge of German occupation policies is shown by his presence at the meeting of 8 August 1942, at which Göring addressed the various German occupation chiefs, told them of the products required from their territories, and added: "It makes no difference to me in this connection if you say that your people will starve."

In the fall of 1943, Funk was a member of the Central Planning Board which determined the total number of laborers needed for German industry and required Sauckel to produce them, usually by deportation from occupied territories. Funk did not appear to be particularly interested in this aspect of the forced labor program and usually sent a deputy to attend the meetings, often SS General Ohlendorf, the former chief of the SD inside of Germany and the former commander of Einsatzgruppe D. But Funk was aware that the board of which he was a member was demanding the importation of slave laborers and allocating them to the various industries under its control. As President of the Reichsbank, Funk was also indirectly involved in the utilization of concentration camp labor. Under his direction the Reichsbank set up a revolving fund of 12,000,000 Reichsmarks to the credit of the SS for the construction of factories to use concentration camp laborers. In spite of the fact that he occupied important official positions, Funk was never a dominant figure in the various programs in which he participated. This is a mitigating fact of which the Tribunal takes notice.

Conclusion: The Tribunal finds that Funk is not guilty on Count One but is guilty under Counts Two, Three, and Four.

October 1, 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On the 218th and last day of the trial, sentences are handed own: "Defendant Walter Funk, on the Counts of the Indictment an which you have been convicted, the Tribunal sentences you to imprisonment for life." Upon hearing the verdict, Funk breaks into sobs and bows to the judges before being led away. (Conot)

October 6, 1946 Dr. Pflücker's diary:

October 16, 1946: Those defendants sentenced to jail time endure a sleepless night as the condemned men's' names are called off, one by one, and led to the gallows.

January 1, 1947: From Spandau: The Secret Diaries by Albert Speer: Began the New Year dispiritedly. Swept corridor, a walk, and then to church. Dönitz and I sing louder than usual because Raeder is sick and Funk is due to go to the hospital. (Speer II)

June 3, 1947: The wives of Funk, Hess, Schirach and Göring, are arrested and taken to Goggingen internment camp in Bavaria.

July 8, 1947 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

July 19, 1947: The prisoners are moved to Spandau, near Berlin.

October 4, 1947 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

December 18, 1947 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

May 5, 1948 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

The Russian director, a small energetic man whose name we do not know, appears. We separate. "Why speaking? You know that is verboten." He departs, but shortly afterward he puts in a surprise appearance in the garden. This time Funk and Schirach are caught talking and warned. Schirach comments scornfully, "That is the dictatorship of the proletariat." (Speer II)

February 3, 1949 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

Funk, who occasionally hits on pithy phrases, admonished us today: "Even humane guards are still guards." With the passage of time the seven of us are becoming increasingly cranky and headstrong. Contacts among us have frozen into their early patterns; new friendships have not formed. Funk and Schirach were always close; today they are an inseparable pair, constantly quarreling and making up. Their interests lie chiefly in literature and music. Systematically, they inform each other about their reading, pick out quotations, exchange opinions. Raeder and Funk, making their rounds of the garden as if it were the daily promenade at a fashionable spa, love to talk about their mutual ailments. (Speer II)

February 4, 1949 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

October 18, 1949 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

October 22, 1949 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

December 27, 1949 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

Half an hour later, Funk comes over. "Imagine, Hess just asked me who Rosenberg was." I wonder what is prompting Hess to come out with all these crazy old tricks again. In the evening I have a chance to pay Hess back for his little games. In the library he picks up the memoirs of Schweninger, Bismarck's personal physician. "Who is Bismarck?" he asks with amazing calm. "Don't you know that, Herr Hess? The inventor of the Bismarck herring, of course." Everybody laughs. Hess, insulted, leaves the library cell. Later I go to his cell and apologize. (Speer II)

July 21, 1950 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

October 14, 1950 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

January 1, 1951 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

I object that the cars generators would be running anyhow, to supply current to the spark plugs. He dismisses that; the generator could shut off automatically as soon as the battery was charged. Thus energy would be stored, fuel saved, and this savings could be spent on financing the illumination of highways. Reckoned out for all the cars the people would soon have in Germany, that would easily amount to more than the highway lights could cost. We listen speechless, until at last Funk says ambiguously, "At any rate, Herr Hess, I am glad that you have recovered your health." Hess ponders for a moment, then looks sternly at me and orders me to work out the idea in detail. Whereupon he returns to his cell, pleased with himself. (Speer II)

June 14, 1952 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

October 14, 1952 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

March 19, 1953 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

"Put out the light," Funk says. "Do you see the moon with the stars in front of it? That is the Turkish sign for good luck." Long [the guard] is bored, because Funk showed him the same thing a few minutes ago, and disappears. In the darkness Funk thrusts a cup toward me and whispers, "Quick, drink! To your forty-eighth birthday! What you dream tonight will be fulfilled." Where in the world can he have got this excellent cognac? (Speer II)

March 21, 1953 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

November 14, 1953 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

January 9, 1954 Spandau: The Secret Diaries

March 31, 1954 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

April 9, 1954 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

September 15, 1954 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

November 30, 1954 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

August 1, 1955 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

November 15, 1955 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

"You must write all that down," the Soviet general said, smiling. "I replied to the general that I've already done so," Funk told me. "Several times, in fact. I said I'd written to the Control Commission." Dibrova shook his head. "You must write to the Soviet Ambassador. The Control Commission no longer exists. You have the right to bring up your case. Insist that it be dealt with by a special committee." In parting the general had wished Funk a good recovery. Funk is so sure of the effectiveness of his presentation that he again has hopes of a release soon. He is setting himself deadlines again. (Speer II)

December 27, 1956 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

1957: Funk is released from Spandau due to bad health.

October 15, 1957 Spandau: The Secret Diaries:

May 31, 1960: Funk dies.

[Part Five, 6/7/1945-5/31/1960.] [Part Four, 9/8/1942-5/1945.] [Part Three, 8/27/1939-8/20/1942.] [Part Two, 3/12/1938-8/25/1939.] [Part One, 8/18/1890-2/1938.]Twitter: @3rdReichStudies

Caution: As always, excerpts from

trial testimony should not necessarily be mistaken for fact. It should be

kept in mind that they are the sometimes-desperate statements of

hard-pressed defendants seeking to avoid culpability and shift

responsibility from charges that, should they be found guilty, can possibly

be punishable by death.

Disclaimer:The Propagander!™ includes

diverse and controversial materials—such as excerpts from the writings of

racists and anti-Semites—so that its readers can learn the nature and extent

of hate and anti-Semitic discourse. It is our sincere belief that only the

informed citizen can prevail over the ignorance of Racialist "thought." Far

from approving these writings, The Propagander!™ condemns racism in all

of its forms and manifestations.

Source

Note: The trial portion of this material, which is available

in its entirety at the outstanding Avalon and Nizkor sites, is being presented here

in a catagorized form for ease of study and is not meant to replace these

invaluable and highly recommended sources.

Fair Use Notice: This site—The Propagander!™—may contain

copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically

authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in

our efforts to advance understanding of historical, political, human rights,

economic, democracy, scientific, environmental, and social justice issues,

etc. We believe this constitutes a "fair use" of any such copyrighted

material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In

accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is

distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in

receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. If

you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own

that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright

owner.