August 23, 1939: Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact: The German-Soviet Non-aggression Pact is signed in Moscow. Sometimes called the Ribbentrop-Molotov Agreement of Non-aggression (or simply the ’Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact’), it sets up plans for a 10-year collaboration between Germany and Soviet Russia.

From Schacht’s IMT testimony: I found a very tense situation in the question of Poland, and I used my return as an occasion for writing a letter to Hitler, a letter to [Hermann] Göring, and a letter to Ribbentrop; that is to say the three leading men—in order to inform them that I had come back from India—leaving it to their discretion, and expecting that at least one of them would ask me for an account of my experiences; and then, I should have had an opportunity of talking to the leading men once again. To my very great surprise, I did not get an answer from Hitler at all; I received no reply from Göring; and Herr von Ribbentrop answered me that he had taken note of my letter. There was, therefore, no other way for me but to make my own inquiries regarding the real state of affairs on Poland and, when things became critical, I took the well-known step, which has already been described here by Herr Gisevius; namely the attempt to gain access to the Fuehrer’s headquarters . . . .

[I was going to tell the generals, particularly General von Brauchitsch, at that last moment] that he still had a chance to avert a war. I knew perfectly well that bare economic and general political statements would, of course, accomplish nothing with von Brauchitsch, because he would then certainly have referred to Hitler’s leadership. Therefore, I wanted to say to him something of quite a different nature and, in my opinion, that is of the most decisive significance. I was going to remind him that he had sworn an oath of allegiance to the Weimar Constitution. I wanted to remind him that the Enabling Act did not delegate power to Hitler, but to the Reich Cabinet; and I wanted to remind him that, in the Weimar Constitution, there was, and still is a clause, which has never been annulled, and according to which, war cannot be declared without previous approval by the Reichstag. I was convinced that Brauchitsch would have referred me to his oath sworn to Hitler, and I would have told him: ’`I also have sworn this oath. You have sworn no oath other than your military one, perhaps, but this oath does not in any way invalidate the oath sworn to the Weimar Constitution; on the contrary, the oath to the Weimar Constitution is the one that is valid. It is your duty, therefore, to see to it that this entire question of war or no war be brought before the Cabinet, and discussed there, and when the Reich Cabinet has made a decision, the matter will go before the Reichstag." If these two steps had been taken, then I am firmly convinced that there would have been no war . . . .

I can only confirm that Gisevius’ statement is correct in every single point, and I myself merely want to add that Canaris mentioned, among many reasons, which then kept us from making the visit, that Brauchitsch would probably have us arrested immediately, if we said anything to him against the war, or if we wanted to prevent him from fulfilling his oath of allegiance to Hitler. But the main reason why the visit did not come about was quite correctly stated by Gisevius. Moreover, it is also mentioned by General Thomas, in his affidavit, which we shall later submit. The main reason was: the war was canceled. And so, I went to Munich on a business matter and, to my surprise, while [I was] in Munich, war was declared on Poland; the country was invaded.

August 24, 1939: Pope Pius XII appeals for peace: ... The danger is imminent, but there is still time. Nothing is lost with peace; all can be lost with war. Let men return to mutual understanding! Let them begin negotiations anew, conferring with good will...

August 25, 1939: Colonel Oster, a member of the ’Schwarze Kapelle,’ greets fellow conspirators Schacht and Gisevius with: "The Führer is done for!’ The cause for Oster’s excessive enthusiasm is that Hitler has just cancelled ’Case White,’ the attack on Poland, even as some preliminary units are advancing. (Shirer)

From the IMT testimony of Hans Bernd Gisevius: When we arrived at the OKW and were waiting at a corner of the street, Canaris sent Oster to us. That was the moment when Hitler between six and seven o’clock suddenly ordered Halder to withdraw his order to march. The Tribunal will no doubt remember that Hitler, influenced by the renewed intervention of Mussolini, suddenly withdrew the order to march, which had already been given. Unfortunately, Canaris and Thomas and all our friends were now under the impression that this withdrawal of an order to march was an incredible loss of prestige for Hitler. Oster thought that never before in the history of warfare had a supreme commander withdrawn such a decisive order, in the throes of a nervous breakdown. And Canaris said to me, "Now the peace of Europe is saved for 50 years, because Hitler has now lost the respect of the generals." And, unfortunately, in the face of this psychological change, we all felt that we could look forward to the following days in a quiet frame of mind. So, when three days later, Hitler nevertheless gave the decisive order to march, it came as a complete surprise for our group as well. Oster called me to the OKW; Schacht accompanied me. We asked Canaris again whether he could not arrange another meeting with Brauchitsch and Halder, but Canaris said to me, "It is too late now." He had tears in his eyes and added, "That is the end of Germany."

From Schacht’s IMT testimony: [As Minister without Portfolio I had] one female secretary [and] two or three rooms in my own apartment, which I had furnished as office rooms. [The government] paid me a rental for those rooms. I have stated here repeatedly that, after my retirement from the Reichsbank, I never had a single meeting or conference, official or otherwise ... no one reported to me, nor did I report to anyone else. I received my salary from the Reichsbank, which was due to me by contract, but a minister’s salary was not paid to me. I believe that, as Minister, I received certain allowances to cover expenses; I cannot say that at the moment, but I did not receive a salary as a Minister.

From Schacht’s pre-trial interrogation:

Q: What salary did you receive as Minister without Portfolio?

A: I could not tell you exactly. I think it was some 24,000 marks, or 20,000 marks. I cannot tell you exactly, but it was accounted on the salary, and afterward on the pension, which I got from the Reichsbank, so I was not paid twice. I was not paid twice.

Q: In other words, the salary that you received as Minister without Portfolio, during the period you were also President of the Reichsbank, was deducted from the Reichsbank?

A: Yes.

Q: However, after you severed your connection with the Reichsbank in January 1939, did you then receive the whole salary?

A: I got the whole salary because my contract ran until the end of June 1942, I think.

Q: So you received a full salary until the end of June 1942?

A: Full salary and no extra salary but, from the 1st of July 1942, I got my pension from the Reichsbank, and again the salary of the Ministry was deducted from that, or vice versa. What was higher, I do not know; I got a pension of about 30,000 marks from the Reichsbank . . . .

Q: What was the date of your contract?

A: From 8 March 1939, 1940, 1941, 1942. Four years. Four years’ contract.

Q: You were really then given a four-year appointment?

A: That is what I told you. After 1942, I got a pension from the Reichsbank.

Q: What was the amount of your salary and all other income from the Reichsbank?

A: All the income from the Reichsbank, including my fees for representation, amounted to 60,000 marks a year, and the pension is 24,000. You see, I had a short contract but a high pension. As Reich Minister without Portfolio, I had another, I think, also 20,000 or 24,000 marks.

From Schacht’s IMT testimony: The salaries are stated on paper, and are correctly cited here; and I have indeed claimed that I was paid by one source only. I was asked, "What salary did you receive as Reich Minister?" I stated the amount, but I did not receive it, as it was merely deducted from my Reichsbank salary. And the pension, as I see here, is quoted wrongly in one case. I believe I had only 24,000 marks pension, while it says here somewhere that it was 30,000 marks. In my own money affairs, I am somewhat less exact than in my official money affairs. However, I was paid only once, and that is mainly by the Reichsbank, up to--and that also has not been stated here correctly. It was not the end of 1942, but the end of June 1942, that my contract expired. Then the pension began, and it too was paid only once. How those two, that is, the Ministry and Reichsbank, arranged it with each other is unknown to me. It is still in effect today. It has nothing to do with the regime. I hope that I shall still receive my pension; how else should I pay my expenses?

August 29, 1939: Ernst von Weizsaecker—State Secretary in the Foreign Ministry—learns of a secret annex to the 1933 Concordat with the Vatican. It stipulates that, in the event Germany introduces universal military training, students studying for the priesthood are declared exempt, except in the case of general mobilization. In that event, most of the diocesan clergy are to be exempt from reporting for service, while all others are to be inducted for pastoral work with the troops, or into the medical corps.September 1, 1939: British Ambassador at the Vatican, Osborne, reports to Lord Halifax that he had suggested to Papal Secretary of State Luigi Maglione that publication of the last-minute unsuccessful peace appeal of Pope Pius XII be accompanied by an expression of regret that the German government, despite the Papal appeal, has plunged the world into war. Maglione, he says, has turned down this request as too specific an intervention into international politics.

September 1, 1939: After some delays, Hitler’s forces invade Poland.

From the IMT testimony of Hans Bernd Gisevius: On the day of the outbreak of war, I was called to Security Intelligence by General Oster, by means of a forged order. However, as it was a regulation that all officers, or other members of the intelligence service, had to be examined by the Gestapo, and as I would never have received permission to be a member of the intelligence, they simply gave me a forged mobilization order. Then, I was at the disposal of Oster and Canaris without doing any direct service.

Immediately after the outbreak of the war, Generaloberst Beck was at the head of all oppositional movements which could exist in Germany at all, with the exception of the Communists, with whom we had no contact at that time. We were of the opinion that only a general could be the leader during war, and Beck stood so far above purely military matters that he was the suitable man to unify all groups, from the left to the right. Beck chose Dr. Goerdeler as his closest collaborator.

No [Schacht and Goerdeler were not the only civilians who worked with our group of conspirators], on the contrary; all the opposition groups, who had so far had merely loose connections with each other, were now drawn together under the pressure of war. This was especially so with the left opposition movements, which had been greatly reduced in the early years, as all their leaders had been interned. These left groups especially now came in with us. In this connection, I shall merely mention Leuschner and Dr. Karl Muehlendorf. However, I must also mention the Christian Trade Unions, and Dr. Habermann, and Dr. Jacob Kaiser.

Further, I must mention the Catholic circles, the leaders of the Confessional Church, and individual political men such as Ambassador von Hassell, State Secretary Planck, Minister Popitz, and many, many others ... the left circles were very much under the impression that the "stab in the back" legend had done much harm in Germany; and the left circles thought that they ought not to expose themselves again to the danger of having it said later, that Hitler or the German Army had not been defeated on the battlefield. The left wing had long been of the opinion that no matter how bitter an experience it might be for them, it must now be proved absolutely to the German people that militarism was committing suicide in Germany.

From Schacht’s IMT testimony: Please forgive me if I say that I assume no responsibility [for the loss of the war by Germany]. Since I am not responsible for the fact that the war started I cannot assume any responsibility for the fact that it was lost. I did not want war.

September 1, 1939: Hitler addresses the Reichstag..From Schacht’s IMT testimony: I did not participate in that meeting at all and I would like to add at once that, during the entire war, I was present at only one meeting of the Reichstag. I could not avoid it, considering the matters that I already mentioned here yesterday. It was after Hitler’s return from Paris. I had to participate in this meeting of the Reichstag, which followed the reception at the station because, as I said, it would otherwise have been too obvious an affront. It was the meeting during which political matters were not dealt with at all, but at which the field marshal’s rank was granted by the dozen . . . .

I do not wish to repeat anything; I merely want to point out that I have already stated repeatedly here that I continually discussed the situation in Germany--thus also my own position--with my friends abroad--not only with Americans, Englishmen, and Frenchmen, but also with neutrals, and I would like to add one more thing: foreign broadcasting stations did not tire at all of speaking constantly about Schacht’s opposition to Hitler. My friends and family received a shock whenever information on this subject transpired in Germany.

From Wilhelm Vocke’s IMT testimony: Now I come to [an] incident, which also leaves no doubt about Schacht’s attitude or the completeness of his information. That was a conversation immediately after the outbreak of the war. In the first few days, Schacht, Huelse, Dreyse, Schniewind and I met for a confidential talk. The first thing Schacht said was: "Gentlemen, this is a fraud such as the world has never seen. The Poles have never received the German offer. The newspapers are lying, in order to lull the German people to sleep. The Poles have been attacked. Henderson did not even receive the offer, but only a short excerpt from the note was given to him verbally. If at any time, at the outbreak of a war, the question of guilt was clear, then it is so in this case. That is a crime the like of which cannot be imagined."

Then Schacht continued: "What madness to start a war with a military power like Poland, which is led by the best French general staff officers. Our armament is no good. It has been made by quacks. The money has been wasted without point or plan."

To the retort: "But we have an air force which can make itself felt," Schacht said: "The air force does not decide the outcome of a war, the ground forces do. We have no heavy guns, no tanks; in three weeks, the German armies in Poland will break down, and then think of the coalition which still faces us." Those were Schacht’s words and they made a deep impression on me

From Schacht’s pre-trial interrogation:

Q: I say, suppose you were Chief of the General Staff and Hitler decided to attack Austria, would you say you had the right to withdraw?

A: I would have said, "Withdraw me, Sir."’

Q: You would have said that?

A: Yes.

Q: So you take the position that any official could at any time withdraw, if he thought that the moral obligation was such, that he felt he could not go on?

A: Quite.

Q: In other words, you feel that the members of the General Staff of the Wehrmacht, who were responsible for carrying into execution Hitler’s plan, are equally guilty with him?

A: That is a very hard question you put to me, Sir, and I answer, "Yes".

From Schacht’s IMT testimony: I should like to give an explanation of this, if the Tribunal permits it. If Hitler ever had given me an immoral order, I should have refused to execute it. That is what I said about the generals also, and I uphold this statement [from my pre-trial interrogation].

September 3, 1939: Radio address by President Roosevelt from Washington:September 8, 1939: US president Franklin D. Roosevelt declares a ’limited national emergency’ due to the war in Europe.

September 12, 1939: Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, head of the Abwehr, protests to General Keitel that extensive shootings are planned in Poland, and that the nobility and intelligentsia are to be exterminated. The world, Canaris prophetically declares, will hold the German armed forces responsible.

September 13, 1939: President Roosevelt calls on Congress to revise Neutrality Law.

September 17, 1939: The USSR invades Poland from the east.

From the IMT testimony of Hans Bernd Gisevius: The main thing for us was, with all possible means, to prevent the war from spreading. It could only spread toward Holland and Belgium, or Norway. We recognized clearly that if a step was taken in this direction, the consequences, not only for Germany, but for the whole of Europe, would be tremendous. Therefore, we wanted to prevent war in the West, by all means.

Immediately after the Polish Campaign, Hitler decided to move his troops from the East to the West, and to launch the attack by violating the neutrality of Holland and Belgium.

We believed that, if we could succeed in preventing this attack in November, we would, in the coming winter months, gain enough time to convince the individual generals, above all Brauchitsch and Halder, and the leaders of the army groups, that they must, at least, oppose the expansion of the war.

Brauchitsch and Halder evaded the question and said it was now too late, that the enemy would fight Germany to the end and destroy her. We did not share this opinion. We believed a peace with honor was still possible, and by honor I mean that we would, of course, eliminate the Nazi hierarchy to the last man. In order to prove to the generals that the foreign powers did not wish to destroy the German people, but wanted only to protect themselves against the Nazi terror, we took all possible steps abroad. The first attempt in that direction, or a small part of that attempt, was the letter written by Schacht to Fraser, the object of which was to point out that certain domestic political developments were imminent and that, if we could gain time, that is, if we could come through the winter, we could perhaps persuade the generals to undertake a revolt.

We wanted to suggest that we, in Germany, were interested in forcing certain developments and, that we now expected an encouraging word from the other side. I do not, however, want any misunderstanding to arise here. In this letter, it also states very clearly that President Roosevelt had, in the meantime, been disappointed many times by the German side, so that we had to beg, to urge him to take such a step. It is a fact that President Roosevelt had taken various steps for peace.

September 21, 1939: Cardinal August Hlond, Primate of Poland, arrives in Rome, and personally reports of German atrocities against Catholic priests in Poland, to the Pope. The Vatican radio and "L’Osservatore Romano" tell the story to the world.

September 28, 1939: Polish Cardinal August Hlond is allowed to broadcast a message to the Poles of the world, over the Vatican Radio. The Pope, unhappy with the cardinal’s presence in Rome, wants him to return to Poland, but the Germans will not allow it.

September 29, 1939: The USSR and Germany divide Poland between them.

November 8, 1939: Johann Georg Elser, a German opponent of Nazism, attempts to assassinate Adolf Hitler at the Burgerbraukeller. Unfortunately, Hitler had left early, and is not there when the bomb explodes. Eight people die, and sixty-three are injured, sixteen of them seriously.

November 9, 1939 Venlo Incident: The German Sicherheitsdienst (Security Service, a sister agency of the Gestapo) engineers the capture of two British SIS (Secret Intelligence Service) agents. Hitler’s government will use the incident as propaganda to link Great Britain to Georg Elser’s failed assassination attempt of German Chancellor Adolf Hitler.

From the IMT testimony of Hans Bernd Gisevius: We tried in every possible way to prove to General Halder and General Olbricht that their theory was wrong, that there could be no longer a question of dealing with a decent German government. We believed that we should now follow a particularly important and safe road. The Holy Father made personal efforts in these matters, as the British Government had, with justification, become uncertain whether there really existed in Germany a trustworthy group of men with whom talks could be undertaken. I remember that, shortly afterwards, the Venlo incident took place when, with the excuse that there was a German opposition group, officials of the English Secret Service were kidnapped at the Dutch border. Therefore, we were anxious to prove that there was a group here, which was honestly trying to do its best and which, if the occasion arose, would stand by its word under all circumstances. I believe that we kept our word regarding the things we proposed to do, while we said quite frankly that we could not bring about this revolt as we had said previously we hoped to do. These negotiations began in October-November 1939. They were only concluded later in the spring . . . .

I believe I must add first that, during November of 1939, General Halder actually had intended a revolt, but that these intentions for a revolt again came to naught because, at the very last minute, Hitler called off the western offensive. Strengthened by the attitude of Halder at that time, we believed that we should continue these discussions at the Vatican. We reached what you might call a gentleman’s agreement, on the grounds of which, I believe that I am entitled to state that we could give the generals unequivocal proof that, in the event of the overthrow of the Hitler regime, an agreement could be reached with a decent civil German government. These were oral discussions, which were then written down in a comprehensive report. This report was read by the Ambassador von Hassell and by Dr. Schacht, before it was given to Halder by General Thomas. Halder was so taken aback by the contents, that he gave this comprehensive report to Generaloberst von Brauchitsch. Brauchitsch was enraged, and threatened to arrest the intermediary, General Thomas; and thus, this action which had every prospect of success, failed . . . .

Constant attempts were made to influence all generals within our reach. Besides Halder and Brauchitsch, we tried to reach the generals of the armored divisions in the West. I remember, for instance, there was a discussion between Schacht and General Hoeppner. We also tried to influence Field Marshal Rundstedt, Bock, and Leeb. Here, too, General Thomas and Admiral Canaris were the intermediaries. When everything was ready, they would not start.

From Schacht’s IMT testimony: I saw him once in February 1940. At that time, various American magazines and periodicals had requested me to write articles on Germany’s interpretation of the situation, her desires, and her position in general. I had the inclination to do this but, because we were at war, I naturally could not do so without first informing the Foreign Minister. The Foreign Minister advised me that he had nothing against my writing an article for an American periodical but that, before sending off this article, he wanted to have the article submitted for censorship. Of course, that did not appeal to me—I had not even thought of that—and, consequently, I did not write this article.

However, there were further inquiries from America, and I said to myself, "It is not sufficient for me to talk with the Foreign Minister; I must go to Hitler in this matter." So, with that aim, I called on Hitler, who received me very soon after my request, and I told him at that time, among other things, just what my experience with Herr von Ribbentrop had been, and I further told him that I thought it might be quite expedient to write these articles; and that it seemed vital to me to have constantly someone in America, who, by means of the press, et cetera, could enlighten public opinion as to Germany and her interests.

Hitler was favorably impressed with this suggestion of mine and said to me, "I shall discuss this matter with the Foreign Minister." Consequently, this entire matter came to naught.

Then, later, through the good offices of my Co-defendant, Funk, who probably had a discussion at that time with Ribbentrop about this matter, I tried to get at least an answer from Ribbentrop. This answer, given to Funk, was to the effect that it was still too early for a step of that sort. And that was my visit in 1940.

From Schacht’s IMT testimony: As to whether the Leadership Principle is criminal or not, opinions throughout history have been much divided. If we look back through Roman history, we see that, from time to time, in dire periods of distress, a leader was selected to whom everyone else was subordinate. And, if I read Failure of a Mission by Henderson, there, too, I find sentences in which he says: "People in England sometimes forget, and fail to realize that even dictators can be, up to a point, necessary for a period, and even extremely beneficial for a nation."

Another passage from the same book says: "Dictatorships are not always evil."

In other words, it depends on just what is attributed to a Führer, how much confidence one has in a Fuehrer, and for how long a time. Of course, it is a sheer impossibility for someone to assume the leadership of a country without giving the nation, from time to time, an opportunity of saying whether it still wants to keep him as Fuehrer or not. The election of Hitler as Führer was, in itself, no political mistake; in my opinion, one could have introduced quite a number of precautionary limitations, with a view to averting the danger you have mentioned. I regret to say that that was not done, and that was a great mistake. But perhaps one was entitled to rely on the fact that, from time to time, a referendum, a plebiscite, a new expression of the will of the people would take place, by which the Führer could have been corrected, because a leader who cannot be corrected becomes a menace. I recognized that danger very well, I was afraid of it, and I attempted to meet it. May I say one more thing? Limitless Party propaganda attempted to introduce the idea of a Führer as a lasting principle into politics. That, of course, is utter nonsense, and I took the opportunity—I always took such opportunity whenever it was possible—of expressing my dissenting opinions publicly. I took the opportunity in an address to the Academy of German Law, of which, not only Nazis but lawyers of all groups were members, and in that speech I lectured about the Leadership Principle in economics. And I expressed myself ironically and satirically, as unfortunately is my wont, and said that it was not necessary to have a leader in every stocking factory: that in fact, this principle was not a principle at all, but an exceptional rule which had to be handled very carefully.

From Schacht’s IMT testimony: Before the invasion of Belgium, I was visited on the order of the Chief of the General Staff, Halder, by the Quartermaster General, the then Colonel, later General Wagner who, after the collapse, committed suicide. He informed me of the intended invasion of Belgium. I was shocked, and I replied at that time, "If you want to commit that insanity too, then you are beyond help." [This] visit ... of Quartermaster General Wagner, upon order of the Chief of General Staff Halder, was intended to persuade me to act in Germany’s interest, during the expected occupation of Belgium. I was to supervise and direct currency, finance, and banking matters in Belgium. I flatly refused that. Later, I was approached again by the then Military Governor of Belgium, General von Falkenhausen, for advice concerning the Belgian financial administration. I again refused to give advice, and did not make any statements, or participate in any way.

May 12-13, 1940: The largest tank battle up to this date occurs in neutral Belgium: the Battle of Hannut.June 22, 1940: France signs an armistice with Germany.

From the IMT testimony of Hans Bernd Gisevius: After the fall of Paris, our group had no influence at all, for months. Hitler’s success deluded everyone, and it took much effort on our part, through all channels available, to try at least to prevent the bombardment of England. Here again, the group made united efforts and we tried, through General Thomas and Admiral Canaris and others, to prevent this evil.

From Schacht’s IMT testimony: As long as I have been President of the Reichsbank, that is to say from March 1933—and I am, of course, only talking about the Hitler regime—my friends and acquaintances abroad were fully informed about my attitude and views. I had a great many friends and acquaintances abroad, not only because of my profession, but also outside of that, and particularly in Basel, Switzerland, where we had our monthly meeting at the International Bank, with all the presidents of the issuing banks of all the great and certain neutral countries, and I always took occasion at all these meetings to describe quite clearly the situation in Germany to these gentlemen.

Perhaps I may at this point refer to the so-called conducting of foreign conferences or conversations. If one is not allowed to talk to foreigners any more, then one cannot, of course, reach an understanding with them. Those silly admonitions, that one had to avoid contact with foreigners, seem entirely uncalled for to me, and if the witness Gisevius deemed it necessary, the other day, to protect his dead comrades, who were my comrades too, from being accused of committing high treason, then I should like to say that I consider it quite unnecessary. Never at any time, did any member of our group betray any German interests. To the contrary, he fought for the interests of Germany and, to prove that, I should like to give you a good example:

After we had occupied Paris, the files of the Quai d’Orsay were confiscated, and were carefully screened by officials from the German Foreign Office. I need not assure you that they were primarily looking for proof whether there were not any so-called defeatist circles in Germany, which had unmasked themselves somewhere abroad. All the files of the Quai d’Orsay referring to my person and, of course, there were records of many discussions [that] I had had with Frenchmen, were examined by the Foreign Office officials at that time, without my knowing it.

From Schacht’s IMT testimony: At the close of the French campaign, when Hitler returned triumphant and victorious from Paris, all of us--the ministers and the Reichsleiter, and the other dignitaries of the Party, as I assume, and state secretaries, and so forth, received an invitation from the Reich Chancellery to be present at the Anhalt Railway Station, to greet Hitler on his arrival. Since I was in Berlin at the time, it was impossible for me to refuse this invitation. It was 1940; the conflict between Hitler and myself had been going on for some time, and it would have been a veritable affront if I had stayed at home. Consequently, I went to the station and saw a very large number of Party dignitaries, ministers and so forth but, of course, I do not remember any more just who all these people were.

I personally did not see that film [a newsreel of the reception], but my friends told me about it. They mentioned especially that, among all the gold braid, I was the only civilian in street clothes there. Of course, it could be ascertained from the film who was present at the time.

I mentioned this reception, for it might be possible that I said "Good morning" to many people, and inquired about their health and so forth; and I also recall that I arrived at the station with the Co-defendant Rosenberg in the same car, because there were always two people to a car. I did not attend the reception which followed at the Reich Chancellery. Rosenberg did go, but I said, "No, I would rather not go. I am going home."

Hitler addressed me, and that was one of the strangest scenes of my life. We were all standing in line, and Hitler passed everyone by, rather quickly. When he saw me, he came up to me with a triumphant smile, and extended his hand in a cordial manner—something which I had not seen from him for a long time—and he said to me, "Now, Herr Schacht, what do you have to say now?" Then, of course, he expected me to congratulate him, or express my admiration or a similar sentiment, and to admit that my prognostication about the war, and about the disaster of the war was wrong, for he knew my attitude about the war quite exactly. It was extremely hard for me to avoid such an answer, and I searched my mind for something else to say, finally replying: "I can only say to you, ’God protect you.’ "That was the only significant conversation [that] I had that day. I believed the best way to have kept my distance was through just such a completely neutral and inconsequential remark.

From Schacht’s IMT testimony: [This letter] concerns a rivalry between two large banks. Both these large banks approached me--as a former banker and President of the Reichsbank--to decide the matter, and I did. I really do not see what that has to do with the official participation in the Belgian administration . . . . Certainly [the purpose of my intervention was to avoid misunderstanding in the occupied countries between the banking interests of the occupied countries and the German banks], they were to work together peacefully . . . . Of course [I was entirely opposed to the Germans being in there at all]. But now that they were there I tried to keep peace.

February 1941: Schacht meets with Hitler.From Schacht’s IMT testimony: In 1941, in February, I called on Hitler once more because of a private affair. The year before, my wife had died, and now I intended to remarry. As Minister without Portfolio, which I still was, I naturally had to inform the Reich Chancellor and head of the State of my intention, and I called on him for that reason. There was no political discussion on this occasion. As I was going to the door, he asked me, "At one time you had the intention, or you advised me, that someone should go to America. It is probably too late for that, now." I replied immediately, "Of course, it is too late for that now." And that was the only remark of a political nature made. The conversation dealt mainly with my marriage and, since then, I did not see Hitler any more.

February 28, 1941: From notes of a conference between General Thomas and his subordinates:1. The whole organization to be subordinate to the Reich Marshall. Purpose: Support and extension of the measures of the Four Year Plan.

2. The organization must include everything concerning war economy, excepting only food, which is said to be made already a special mission of State Secretary Backe.

3. Clear statement that the organization is to be independent of the military or civil administration. Close co-ordination, but instructions direct from the central office in Berlin.

4. Scope of activities to be divided into two steps: a) Accompanying the advancing troops directly behind the front lines, in order to avoid the destruction of supplies, and to secure the removal of important goods; b) Administration of the occupied industrial districts, and exploitation of economically complementary districts.

5. In view of the extended field of activity, the term ’war economy inspection’ is to be used in preference to armament inspection.

6. In view of the great field of activity, the organization must be generously equipped, and personnel must be correspondingly numerous. The main mission of the organization will consist of seizing raw materials, and taking over all important exploitations. For the latter mission, reliable persons from German concerns will be interposed suitably from the beginning, since successful operation from the beginning can only be performed by the aid of their experience. (For example: lignite, ore, chemistry, petroleum).

After the discussion of further details, Lieutenant Colonel Luther was instructed to make an initial draft of such an organization, within a week. Close co-operation with the individual sections in the building is essential. An officer must still be appointed for the Wi and Ru, with whom the operational staff can remain in constant contact. Wi is to give each section chief—and Lieutenant Colonel Luther—a copy of the new plan regarding Russia. Lieutenant General Schubert is to be asked to be in Berlin, the second half of next week. Also, the four officers who are ordered to draw up the individual armament inspections are to report to the office chief at the end of the week. signed—Hamann.

From the IMT testimony of Hans Bernd Gisevius: We have now come to the year 1941 and, on this trip to Switzerland, Schacht tried to urge that a peace conference should be held, as soon as possible. We knew that Hitler was thinking about the attack on Russia, and we believed that we should do everything to avert, at least, this disaster. With this thought in mind, Schacht’s discussions in Switzerland were conducted. I myself took part in arranging a dinner in Basel, with the president of the B. I. Z., Mr. McKittrick, an American, and I was present when Schacht tried to express, at least, the opinion that everything possible must now be done to initiate negotiations. I can say only that Schacht knew of all the many attempts [that] we undertook to avert this catastrophe [Barbarossa].

From Schacht’s IMT testimony: [On my trip to Switzerland] I tried, again and again, to shorten the war and to bring about some form of mediation, which I always sought for, particularly through the good offices of the American President. That is all that I can say here. I do not think I need go into details . . . .

In the summer of 1941, I wrote a detailed letter to Hitler, and the witness Lammers has admitted its existence. I do not think he was asked about the contents of this letter here, or he was not allowed to talk about it. If I may come back to it, in that letter, I pointed out somewhat as follows—I shall use direct language—"You are at present at the height of your success." This was after the first Russian victories. "The enemy believes that you are stronger than you really are. The alliance with Italy is rather a doubtful one, since Mussolini will one day fall, and then Italy will drop out. Whether Japan can still come to your aid at all, is questionable in view of Japan’s weakness in the face of America. I assume that the Japanese will not be so foolish as to wage war against America. The output of steel, for instance, in spite of approximately similar population figures, amounts to one-tenth of the American production. I do not think, therefore, that Japan will enter into the war. I now recommend you, at all events, to reverse foreign policy completely, and to attempt with every means to conclude a peace."

On one occasion Herr von Ribbentrop conveyed to me through his State Secretary, Herr von Weizsaecker, the reproachful message that I should not indulge in defeatist remarks. That may have been in 1940 or in 1941, during one of those two years. I asked where I had made defeatist remarks, and it appeared that I had talked to my colleague Funk, and had given him extensive reasons why Germany could never win this war. I held this conviction unchangeable at all times, before and during the war, even after the fall of France. I answered Ribbentrop through his State Secretary that I, as Minister without Portfolio, considered it my duty to state my opinion to a ministerial colleague, in its true conception, and in this written reply, I maintained the view that Germany’s economic power was not sufficient to wage this war. This letter, that is a copy of this letter, was sent both to Minister Funk, and to Minister Ribbentrop, through his State Secretary.

From a pre-trial interrogation of Schacht:

Q: What was there in what he [Hitler] said that led you to believe he was intending to move towards the east?

A: That is in Mein Kampf. He never spoke to me about that, but it was in Mein Kampf.

Q: In other words, as a man who read it, you understood that Hitler’s expansion policy was directed to the east?

A: To the east.

Q: And you thought that it would be better to try to divert Hitler from any such intention, and to urge upon him a colonial policy instead?

A: Quite.

From the affidavit of Admiral Otto Schniewind, Swedish Consul General at Munich: My department dealt with the Reich guarantees for deliveries to Russia, and thus I was in position to know that Schacht considered Hitler wrong, in fighting Russia. Through much effort, he obtained Hitler’s permission to send extensive supplies, especially machines, to Russia. Frequently, I gained the impression that Herr Schacht favored these deliveries because, while instrumental in giving employment, they did not benefit rearmament. Herr Schacht, on several public occasions, pointed out with satisfaction that trade shipments to Russia were proceeding promptly and smoothly.

From the IMT testimony of Dr. Hans Heinrich Lammers, Chief of the Reich Chancellery: The first application for resignation [submitted by Schacht] was handed in, because it had been prohibited to listen to foreign broadcasting stations. Schacht was thereby forbidden to listen to many foreign stations; and he complained about it, and handed in an application for resignation, whether in writing or verbally, I do not know. The request was refused, and later, he submitted a memorandum, in which he discussed the end of the war, and the political and economic situation. I had to tell Schacht, in answer to this memorandum, that the Fuehrer had read it, and had nothing to say in reply. Thereupon, in 1942, Schacht again asked me to ask the Fuehrer if he was disposed to receive another memorandum. At this, the Führer gave me the order to write to Schacht, and tell him to refrain from submitting any further memoranda . . . .

I think that, in this memorandum, Herr Schacht set forth the economic capacities of Germany and of foreign countries, that he pointed out that this period in 1941--I believe it was in the autumn--was the most favorable moment for peace negotiations, for bringing the war to an end. He also explained the world situation, but I cannot remember how. He sketched the political situation in other countries. He talked about America, Italy, Japan, and he compared the factors. After the Führer had looked at the memorandum, he put it aside and he said, "I have already disapproved of that; I do not want that." Further details I do not know.

From Schacht’s IMT testimony: I could perhaps relate another instance when I was approached. One day, shortly after America was drawn into the war, I received a request from the newspaper published by Goebbels that, on account of my knowledge of American conditions, I should write an article for Das Reich, to assure the German people that the war potential of the United States should not be overestimated. I refused to write that article, for the reason that precisely because I knew American conditions very well, my statement could only amount to the exact opposite. And so I refused in this instance also.

September 8, 1942: Churchill addresses the House:November 19, 1942: The Red Army unleashes Operation Uranus, the counter-attack at Stalingrad.

November, 1942: Schacht to Göring (See: January 21, 1943):

From Schacht’s IMT testimony: On every occasion when I was no longer in a position to do what my inner conviction demanded, I said, "No." I was not content to be silent in the face of the many misdeeds committed by the Party. In every case, I expressed my disapproval of these things, personally, officially, and publicly. I said "No" to all those things. I blocked credits. I opposed an excessive rearmament. I talked against the war, and I took steps to prevent the war. I do not know to whom else this honorary title of "No man" might apply, if not to me . . . .

Yes, the letter had very considerable consequences. It had the result that, on 22 January, I did at last receive my long hoped-for release from my position of a nominal Minister without Portfolio. The reason given for it, however, was less pleasant. I believe the letter is already in the files of the Tribunal. It is a letter attached to the official document of release from Lammers.

From the IMT testimony of Hans Bernd Gisevius: When we did not succeed in persuading the victorious generals to engineer a revolt, we then tried at least to win them over to one, when they had obviously come up against their great catastrophe. This catastrophe, which found its first visible signs in Stalingrad, had been predicted in all its details by Generaloberst Beck since December of 1942. We immediately made all preparations so that, at the moment [that] could be forecast with almost mathematical exactitude, when the army of Paulus, completely defeated, would have to capitulate, then at least a military revolt could be organized. I myself was called back from Switzerland, and participated in all discussions and preparations. I can only testify that, this time, a great many preparations were made. Contact was also made with the field marshals in the East, with Witzleben in the West, but again, things turned out differently, for Field Marshal Paulus capitulated, instead of giving us the cue at which Kluge, according to plan, was to start the revolt in the East ... from the moment when the generals again deserted us, we realized that a revolt was not to be hoped for and, from that moment on, we took all the steps we could, to instigate an assassination.

January 21, 1943: Göring to Schacht:My answer to your defeatist letter [November, 1942], that undermines the powers of resistance of the German people, is that I expel you herewith from the Prussian State Council.

From the IMT testimony of Hans Bernd Gisevius: By chance, I was in Berlin on the day this letter of dismissal arrived. It was an unusually sharp letter, and I remember that, that night, I was asked to the country house of Schacht, and as the letter had simply stated that Schacht was to be dismissed, we wondered whether he was also going to be arrested.

From Schacht’s IMT testimony: It was, therefore, my entire attitude during this war [that] led to my dismissal, and the letter of dismissal also contained the statement that I would be dismissed for the time being. According to Lammers’ statement, as we have heard, this expression "for the time being" was included in the letter, also on the Fuehrer’s initiative. I was very clearly aware of this wording when I received the letter.

Two days later, I was removed from the Prussian State Council, of which I was a member, a body, incidentally, which had not met for at least 8 years. At any rate, I was not at the meetings. Perhaps it was 6 years, I do not know, The text of that decision was communicated to me by the chairman of that State Council, Hermann Göring and, because of its almost amusing contents, I still recollect it very clearly. It stated:

"My answer to your defeatist letter undermining the power of resistance of the German people is that I remove you from the Prussian State Council."

I say it was amusing because a sealed letter written by me to Göring could not possibly shake the power of resistance of the German people. A further result was that Party Leader Bormann demanded from me the return of the Golden Party Badge, and I did that at once. After that, I was particularly closely watched by the Gestapo. I gave up my residence in Berlin immediately, within 24 hours and, for the whole day, the Gestapo spies followed me all over Berlin, both on foot and by car. Then I quietly retired to my estate in the country . . . .

A few months ago [that is, in 1946, during the trial], apparently with the approval of the Military Government, there appeared in the press a list of donations [that] the Party leaders and ministers in Germany received and, in that connection, of their income and their property. I was also listed, not under "donations," but it was stated that in 1942 I had an unusually high income. This list is incorrect, since it is a gross figure that is mentioned and it does not take into consideration the fact that the war profit tax was later deducted from it. When the list was compiled, the tax was not yet determined, so that about 80 percent must be deducted from the sum which is given there. The income is then no longer striking in any way. In regard to my property, the list shows that over a period of 10 years it has hardly changed, and I want to emphasize here particularly that, in the last 20 years, my property remained approximately the same, and did not increase . . . .

I wish to add something to this. From dozens of witnesses who have testified here, and from myself, you have heard, again and again, that it was impossible unilaterally to retire from this office because, if I was put in as a minister by the head of a government, I could also be retired only with his signature. You have also been told that, at various times, I attempted to rid myself of this ministerial office. Besides the witnesses’ testimony from countless others, including Americans, to the effect that it was well known that Hitler did not permit anyone to retire from office without his permission. And now you charge me with having remained. I did not remain for my pleasure, but I remained because I could not have retired from the Ministry without making a big row. And almost constantly, I should say, I tried to have this row, until finally, in January 1943, I succeeded; and I was able to disappear from office, not without danger to my life. The letter, by which I brought about the last successful row, is dated 30 November 1942. The row and its success dates from 21 January 1943, because Hitler and Göring, and whoever else participated in discussing it, needed seven weeks to make up their minds about the consequence of my letter.

My oral and written declarations from former times have already shown [that I thought the ship was sinking]. I have spoken here also about this. I have testified on the letter to Ribbentrop and Funk; I have presented a number of facts here, that prove that I never believed in the possibility of a German victory. And my disappearance from office has nothing whatsoever to do with all these questions.

March 13, 1943: During a visit by Hitler to Army Group Center Headquarters in Smolensk, Fabian von Schlabrendorff smuggles a time bomb, disguised as bottles of cognac, [on board] the aircraft [that] carries Hitler back to Germany. The bomb detonator fails to go off, however, most likely because of the cold in the aircraft. Schlabrendorff manages to retrieve the bomb the next day, and elude detection.

From the IMT testimony of Hans Bernd Gisevius: It was said, at that time, that there was now nothing left for us, but to free Germany, Europe, and the world from the tyrant, by a bomb attack. Immediately after this decision, preparations were started. Oster spoke to Lahousen, and Lahousen furnished the bombs from his arsenal. The bombs were taken to the headquarters of Kluge at Smolensk and, with every possible means, we tried to bring about the assassination, which was unsuccessful only because, at a time when Hitler was visiting the front, the bomb [that] had been put in his airplane did not explode. This was in the spring of 1943 . . . .

Gradually, even Himmler could not fail to see what was happening in the OKW and, at the urgent request of SS General Schellenberg, a thorough investigation of the Canaris group was now started. A special commissioner was appointed and, on the first day of this investigation, Oster was relieved of his post, and a number of his collaborators were arrested. A short time afterwards, Canaris was also dismissed from his post. I myself could no longer remain in Germany and thus, this group, which until now had, in a certain sense, been the directorate of all the conspiracies, was eliminated.

From Colonel Gronau’s affidavit:

Question 5) You brought Schacht and General Lindemann together. When was that?

Answer 5) In the fall of 1943, for the first time in years, I again saw General Lindemann, my former school and regiment comrade. While discussing politics, I told him that I knew Schacht well, and General Lindemann asked to be introduced to him, whereupon I established the connection.

Question 6) What did Lindemann expect from Schacht, and what was Schacht’s attitude toward him?

Answer 6) The taking up of political relations with foreign countries, following a successful attempt at revolt. He promised his future co-operation. At the beginning of 1944, Lindemann made severe reproaches that the generals (that should read "he severely reproached Lindemann"; it is incorrectly copied here) because the generals were hesitating so long. The attempt at revolt would have to be made prior to the landing of the Allies.

Question 7) Was Lindemann involved in the attempted assassination of 20 July 1944?

Answer 7) Yes, he was one of the main figures.

Question 8) Did he inform Schacht of the details of this plan?

Answer 8) Nothing about the manner in which the attempt was to be carried out; he did inform him, however, of what was to happen thereafter.

Question 9) Did Schacht approve the plan?

Answer 9) Yes.

Question 10) Did Schacht put himself at the disposal of the military, in the event of a successful attempt?

Answer 10) Yes.

Question 11) Were you arrested after 20 July 1944?

Answer 11) Yes.

Question 12) How were you able to survive your imprisonment?

Answer 12) By stoically denying complicity.

February 1944: Hitler dismisses Admiral Wilhelm Franz Canaris, a member of the German Resistance, from the Abwehr. He is replaced by Walter Schellenberg.

From the IMT testimony of Hans Bernd Gisevius: A few months after the elimination of the Canaris-Oster circle, we formed a new group around General Olbricht. At that time Colonel Count von Stauffenberg also joined us. He replaced Oster in all activities and when, after several months, and after many unsuccessful attempts and discussions, the time finally arrived in July 1944, I returned secretly to Berlin, in order to participate in the events. No [I had no direct connection with Schacht]; I, personally, was in Berlin secretly, and saw only Goerdeler, Beck, and Stauffenberg; and it was agreed expressly, at this time, that no other civilian except Goerdeler, Leuschner, and myself [was] to be informed of the matter. We hoped, thus, to protect lives by not burdening anyone unnecessarily with this knowledge . . . .

I would like to emphasize that the problem of Schacht was confusing, not only to me, but to my friends as well; Schacht was always a problem and a puzzle to us. Perhaps it was due to the contradictory nature of this man, that he kept his position in the Hitler government for so long. He undoubtedly entered the Hitler regime for patriotic reasons, and I would like to testify here that, the moment his disappointment became obvious, he decided for the same patriotic reasons to join the opposition. Despite Schacht’s many contradictions, and the puzzles he gave us to solve, my friends and I were strongly attracted to Schacht, because of his exceptional personal courage, and the fact that he was undoubtedly a man of strong moral character, and he did not think only of Germany, but also of the ideals of humanity. That is why we went with him, why we considered him one of us; and, if you ask me personally, I can say that the doubts [that] I often had about him were completely dispelled, during the dramatic events of 1938 and 1939. At that time, he really fought, and I will never forget that. It is a pleasure for me to be able to testify to this here.

From Schacht’s IMT testimony: I knew about it. I already stated yesterday that I was informed not only of Goerdeler’s efforts, but that I was thoroughly informed by General Lindemann; and the evidence of Colonel Gronau has been read here. I also stated that I did not inform my friends about this, because there was a mutual agreement between us, that we should not tell anyone anything [that] might bring him into an embarrassing situation, in case he were tortured by the Gestapo. You see that even Gisevius was not informed on every detail. Naturally, he cannot testify to more than what he knew.

July 22, 1944: Hitler orders Schacht’s arrest, accusing him of being complicit in the Bomb Plot.From Schacht’s IMT testimony: Codefendant Minister Speer was present [when Hitler ordered my arrest] and told me about it. It was on 22 July 1944, when Hitler issued the order to his circle for my arrest. At that time, he made derogatory remarks about me, and stated that he had been greatly hindered in his rearmament program by my negative activities, and that it would have been better if he had had me shot before the war . . . .

I can only state that, first of all from 1920, until the seizure of power by Hitler, I tried to influence the nation and foreign countries, in a way [that] would have prevented the rise and seizure of power by a Hitler. I warned the country to be thrifty, but I was not heeded. I repeatedly warned the foreign nations to develop an economic policy [that] would enable Germany to live. I was not heeded although, as it now appears, I was considered a clever and foresighted man. Hitler came to power because my advice was not followed.

From the IMT testimony of Hans Bernd Gisevius: Schacht was the only one who was put into a concentration camp. But it is true that we all asked ourselves just how long it would take for a Reich Minister to be sent to a concentration camp . . . .

I would like to add that we were not only thinking of the great dangers outside, but we also realized what dangers lay in such a system of terror. From the very beginning, there was a group of people in Germany who still did not even think of the possibility of war, and nevertheless protested against injustice, the deprivation of liberty, and the fight against religion.

In the beginning, therefore, it was not a fight against war, but if I may say so, it was a fight for human rights. From the very first moment on, among

all classes of people, in all professional circles, and in all age groups, there were people who were ready to fight, to suffer, and to die for that idea.

I should like to say that death has reaped such a rich harvest among the members of the resistance movement, that it is only for that reason I can sit here and that, otherwise, more worthy and able men could give this answer. Having said this, I feel that I can answer that, whether Jew or Christian, there were people in Germany who believed in the freedom of religion, in justice, and human dignity, not only for Germany but also, in their profound responsibility as Germans, for the higher concept of Europe and the world. It was not only just a group, but many individuals had to carry the secret of their resistance silently to their death, rather than confide it to the Gestapo records; and only a very few persons have enjoyed the distinction of being referred to now as a group.

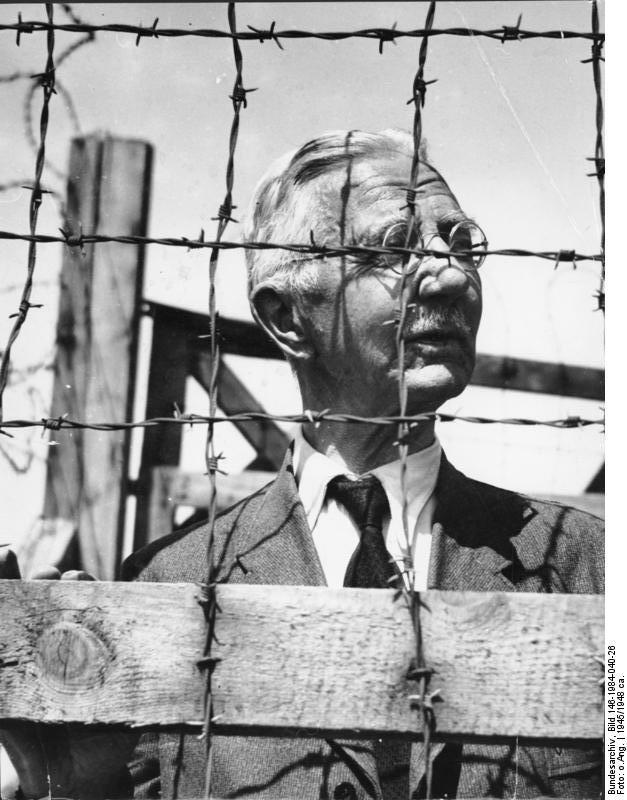

From Schacht’s IMT testimony: I had an opportunity of acquainting myself with several concentration camps when, on 23 July 1944, I myself was dragged into a concentration camp. Before that date, I did not visit a single concentration camp at any time, but afterwards I got to know not only the ordinary concentration camps but also the extermination camp in Flossenburg.

April 1945: Schacht and about 140 other prominent inmates of Dachau are transferred to the Tyrol by the SS.From The Nuremberg Trial by Joe J. Heydecker and Johannes Leeb: Ravensbrück, Moabit, and finally the extermination camp of Flossenburg were his stopping places. ’No one gets out alive from this camp,’ Schacht whispered to his fellow prisoners when he was brought in. Through the open door of a shed in the camp, there was a view of the scaffolding of the gallows. Every night, Schacht heard the screams and shots which left no doubt what was happening. Many a morning, as he took his exercise, he could count up to thirty dead being carried away on stretchers from the places of execution. Only much later, Schacht learned that the commandant of Flossenburg had been expressly ordered to shoot him, as soon as the Allies came anywhere near the camp. But it did not come to that. In the face of imminent defeat, the SS suddenly attempted to introduce a more humane treatment, perhaps in the hope of thereby saving themselves. Thus Schacht, together with other prisoners, was transferred first to Dachau, and later to Austria, when the Americans advanced. As the transport halted at the Pragser Wildsee, the Ninth Army liberated him and, with him, a number of others who were internees and "VIP prisoners" of Hitler ... (among them: Pastor Martin Niemöller, Miklos Kallay, Bruno Bettelheim, Kurt von Schuschnigg, Fritz Thyssen, Leon Blum, Nicholas von Horthy, [Alext Kokosin?], Franz Halder, Peter Churchill) . . . .

"Why did Hitler put you in jail? Schacht was asked by the Americans. ’No idea,’ answered the banker. He also had no idea why he was not set free, but kept under arrest. He was well treated, he had excellent food, and was allowed to walk unguarded by the Pragser lake. But then, he was moved again, and by various stages reached eventually the overcrowded prisoner-of-war camp Aversa, near Naples. Hjalmar Schacht, the financial genius with the old-fashioned stand-up collar, had changed sides several times. Now, he was on his way to the prison at Nuremberg.

May 2, 1945: Executive Order of US President Truman:

May 5, 1945: Schacht is arrested by the US Fifth Army.

[Next: Part Eight, Click Here.] [Back: Part Six, Click Here.] [Back: Part Five, Click Here.] [Back: Part Four, Click Here.] [Back: Part Three, Click Here.] [Back: Part Two, Click Here.] [Back: Part One, Click Here.] Written by Walther Johann von Löpp Copyright © 2011-2016 All Rights Reserved Edited by Levi Bookin — Copy Editor European History and Jewish Studies

Twitter: @3rdReichStudies

Caution: As always, excerpts from

trial testimony should not necessarily be mistaken for fact. It should be

kept in mind that they are the sometimes-desperate statements of

hard-pressed defendants seeking to avoid culpability and shift

responsibility from charges that, should they be found guilty, can possibly

be punishable by death.

Disclaimer:The Propagander!™ includes

diverse and controversial materials—such as excerpts from the writings of

racists and anti-Semites—so that its readers can learn the nature and extent

of hate and anti-Semitic discourse. It is our sincere belief that only the

informed citizen can prevail over the ignorance of Racialist "thought." Far

from approving these writings, The Propagander!™ condemns racism in all

of its forms and manifestations.

Source

Note: The trial portion of this material, which is available

in its entirety at the outstanding Avalon and Nizkor sites, is being presented here

in a catagorized form for ease of study and is not meant to replace these

invaluable and highly recommended sources.

Fair Use Notice: This site—The Propagander!™—may contain

copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically

authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in

our efforts to advance understanding of historical, political, human rights,

economic, democracy, scientific, environmental, and social justice issues,

etc. We believe this constitutes a "fair use" of any such copyrighted

material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In

accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is

distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in

receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. If

you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own

that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright

owner.